Biography

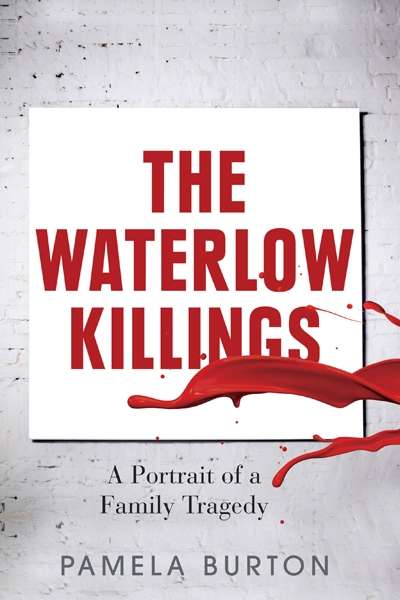

The Waterlow Killings: A Portrait of a Family Tragedy by Pamela Burton

by Alison Broinowski •

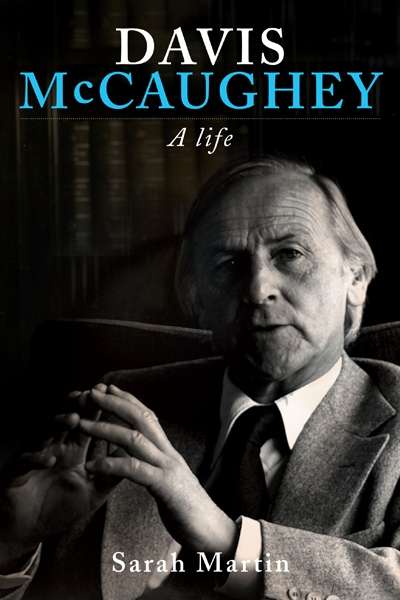

Davis McCaughey: A Life by Sarah Martin

by Chris Wallace-Crabbe •

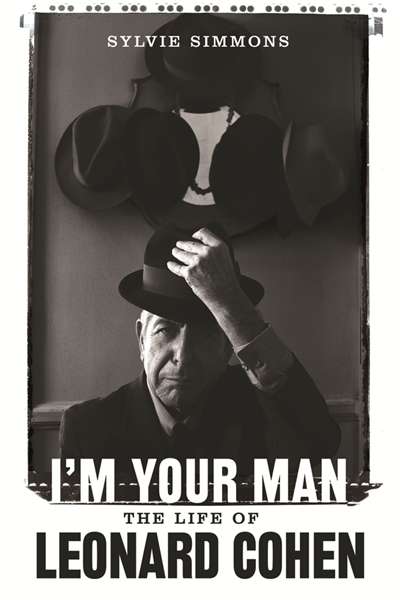

I'm Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen by Sylvie Simmons

by David McCooey •

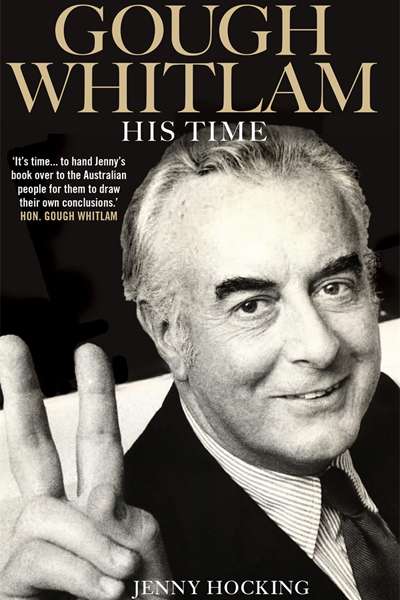

Gough Whitlam: His Time: The Biography, Volume II by Jenny Hocking

by Neal Blewett •

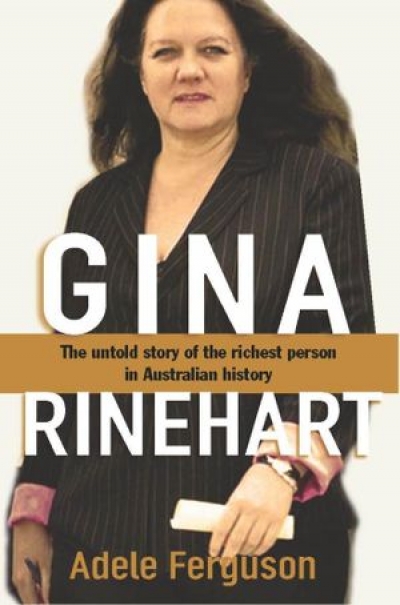

Gina Rinehart by Adele Ferguson & The House of Hancock by Debi Marshall

by Jan McGuinness •

The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Passage of Power by Robert A. Caro

by Peter Heerey •