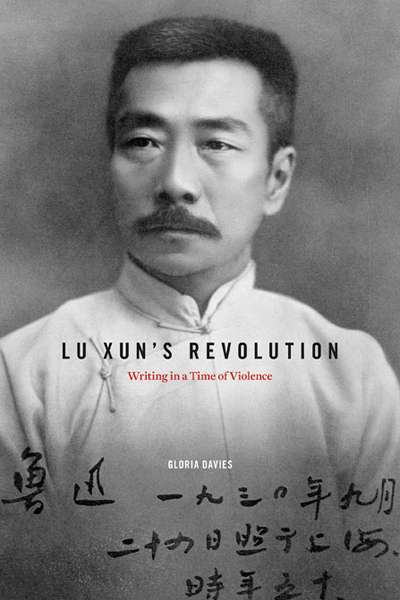

This richly documented study of China’s pre-eminent writer Lu Xun (1881–1936) by Gloria Davies cannot fail to provoke deep reflection on the issue of the creative writer, artist, philosopher, or scholar and his or her involvement in politics. For Lu Xun, the issue was exacerbated by the brutal reality of China in the late 1920s and early 1930s, a ‘time of violence’, as suggested by the book’s subtitle. Highly emotive patriotism had generated political activism, and abstract ‘revolution’ had an uncanny religious aura with its promise of an ideal future society. Violence came from an intense struggle for power, and political parties were defined by an army and an extensive network of informers and assassins: public and secret executions instilled fear in the faint-hearted and, at the same time, produced heroes who were prepared to sacrifice themselves. Intellectuals were recruited into the propaganda machinery of the Nationalist Party or the Communist Party, and individuals had no option but to adopt a political stance.

...

(read more)