Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage

Harvill Secker, $35 hb, 298 pp

Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage by Haruki Murakami

A recent exhibition at Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art included two videos of scenes from modern Japanese life that at first seemed ordinary, even banal. In one, the artist Tabaimo (Ayako Tabata) animates the interior of a train, with views of passing suburbs; in the other, she shows a mansion from a bygone century, opening like a doll’s house to display its plush furnishings. But then things begin to change. Human body parts appear on the train’s luggage racks, an egg on the floor explodes, and the view of the next carriage morphs into a caged prison. Squid-like tentacles penetrate the house, a door opens to reveal a pulsating brain, and a torrent of water pours out. The climax of the train video shows a man lying on the track becoming a red sun on a white screen; the doll’s house one ends with the flood subsiding, and the two halves of the building closing up. The restored street frontage is bland, but no less puzzling.

Haruki Murakami’s writing reveals a similar aesthetic, like the bizarre fantasies in old woodblock prints. Many of his books, both fact and fiction, begin as blandly as Tabaimo’s videos, with accounts of ordinary life somewhere in modern Japan. Often there is a disingenuous, solitary young man whose parents are remote or absent, a large old house, an elegant older woman, a wise male friend, a worldly girlfriend. As well there is jazz, a particular piece of classical music, casual clothes carefully chosen, a demanding exercise régime, food and wine sparingly consumed at home or in small restaurants, and details of journeys by car or train, often to a dark forest. But all is not as it seems. Inexplicable events and strange physical sensations soon begin to worry the young man who, typically, is too diffident to unburden himself to others. In several of Murakami’s narratives, the young man seems to enter a parallel universe where he is pursued by strange forces, or where he suspects that in another self he has done something dreadful to people close to him.

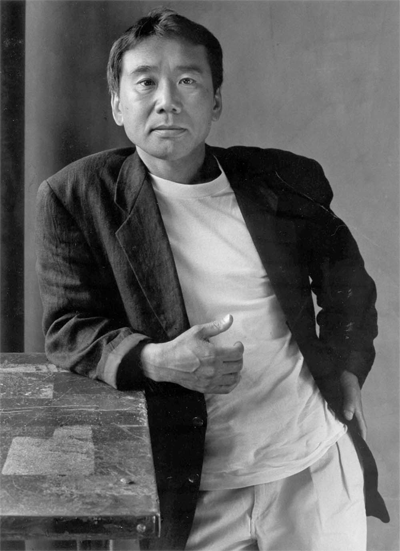

Haruki Murakami (photograph by Emma Seibert)

Haruki Murakami (photograph by Emma Seibert)

Such a universe opens up to Aomame when she climbs down a stair from an overhead expressway, in Murakami’s massive 1Q84 (2009, in English 2011).Her dangerous task is to seek out the leader of a religious cult; in the process she finds Tengo, who is equally puzzled and threatened by the events and people he encounters in that underworld. In Kafka on the Shore (2003, in English 2005), a student who runs away from home and school is given refuge in a private library supervised by an enigmatic elderly lady. Kafka – as he calls himself, choosing an idiosyncratic name as several of Murakami’s young people do – comes to believe that he is guilty of Oedipal patricide and incest. These otherworlds of Murakami’s invention are the weird, dark underside of Japan’s well-lit, orderly, quotidian society. His non-fiction book Underground (1997, in English 2000), about the 1995 Sarin gas attack on Tokyo subway trains, similarly contrasts the superficial calm and the chaotic depths. Commuters and railway staff who, for their own reasons, did not break out of their morning routine and rush upstairs to the fresh air became the victims of Aum Shinrikyo, a bizarre cult led by a blind guru, whose reason for the attack was never fully explained. At the end, as with much of Murakami’s writing, what’s left is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma, as Churchill said of Russia.

In his new novel, Murakami recombines these familiar ingredients for his devoted public. Tsukuru, a young man who has been dropped without explanation by his four Nagoya schoolfriends, is so deeply hurt that, even after he stops wanting to die, he feels hollow and worthless. He is tormented about what he may, unwittingly or even in another identity, have done to deserve their contempt. But he cannot raise it with them, nor tell his family, so every day he goes to work in Tokyo designing railway stations, and apart from the odd affair that goes nowhere, that is his life. A wise male friend, Haida, puts Tsukuru back in touch with his emotions before he, too, disappears. A slightly older woman, Sara, whom Tsukuru is beginning to love, urges him to find the three former school friends who remain – one has been murdered. He elicits a different story about what happened from each one, in the manner of Rashōmon. There is also a journey to Finland, to a dark forest, where he finds some understanding of the enigma. But the outcome isn’t certain there, nor back in Tokyo: his pilgrimage has no end.

Murakami offers a detailed description of a railway station, this time Shinjuku. Once again there is a chosen theme, Liszt’s ‘Le Mal du Pays’, from Years of Pilgrimage, which the dead school friend played. (When Murakami selects a piece, like the Janáček Sinfonietta in 1Q84, the CD becomes a bestseller in Japan.) As with 1Q84 and Kafka, the novel comes with a striking cover design. This time, coloured circles representing the names of Tsukuru’s four friends make the book instantly recognisable in a shop, or in a train carriage. There is nothing enigmatic about such clever marketing, nor about releasing the novel at midnight like a new iPhone. The hints from reviewers and publishers about a future Nobel Prize for Murakami’s impressive oeuvre are becoming broader.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.