Peter Porter Poetry Prize 2013 Shortlist

Prophecy

cliffs ahead the singing ravine

a horse gallops beside the train never tiring

who is stoking the engine? is the lion tame?

the thorn in the paw was a dream

everything ran on grease and sequins

everybody wore a smoking hand

when Habakkuk rode into the desert

with the lighter and a wafered tongue

a trail of bunting flicks and frets

like a projectionist with a stammer

there was never a bridge the horse the horse

every boom gate is a gallows

the spitfire diving for the dining car

will the yogi come out of his trance?

the jewel on his turban charging the ape

with coveting another man’s wife

the ostrich’s light globe head has blown

red beads across the carriage floor

a flapper girl tied to the tracks ahead

every hoof print the shape of ‘you’

as the standoff continues upon the roof

three winds come clapping for hats

and it burns burns burns the ring of fire

there was never a bridge to be out

*

Habakkuk rides the wincing mule

as if it matters how you travel to your funeral

everything is melting down to murder

the mirage is a cake of trouble

the Russian who said only blood will tell

the sun’s throwing knives never miss

may the dust he returns to catch the light

who has eaten his death cap mushrooms?

the mule knows the dangling carrot is a boot

the mule knows how things go around

how summer reacquaints us with our ugly feet

how Bertha pole dances in a caravan

animals in costumes dream of new costumes

Habakkuk rides like prophecy

his sentence dangling around his neck

rabbits knocking on wood in the cemetery

a tongue that tastes like the body of Christ

the mirage is still a cake

sometimes he hears the squeak of trees

but that must have been days ago

as somebody somewhere plays guitar

and chuckles like firewood

the bearded lady or the ringleader’s wife

he should have chosen the other hand

*

it’s not the storm it’s the debris that kills you

in a hot chilli hallucination

eye floaters steering the eye of the film

avoid contact with the air as much as possible

people’s views aside for a moment

they’re calling it terminal

white goats swimming in a pool of milk

dogs nailed to the ground by thunder

the standoff continues upon the roof

and smoke in the projector’s beam

how to turn away from a beautiful woman

duelling with snarls and squints

the hobbled heart and violent mind

the eagle in the baby pram

the gun he draws becomes a banana

only the lighthouse keeper knows

the extraordinary life she lives without him

if they’d only invested in spray on skin

the ape and the mushrooms come to pass

the abuse of prophecy and group hypnosis

when the only choice is how to fall

down on Habakkuk in the canyon

like a ceiling rose with a beautiful voice

about the horse about ramraid mayhem

Nathan Curnow

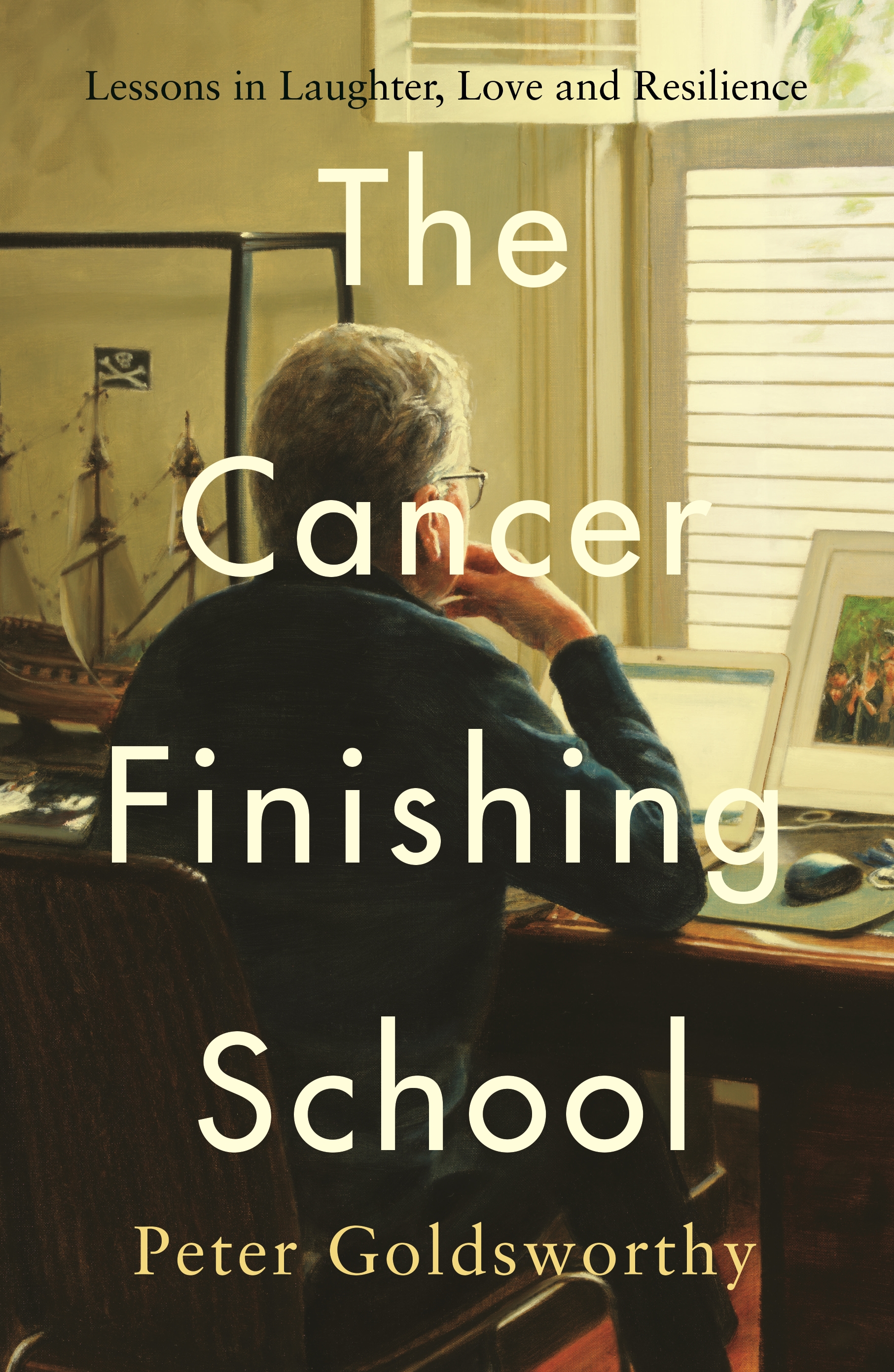

Big Wig

You were no famous footballer, nor footballer’s hungry wife.

You lived in the suburbs and read, cool-eyed,

of proliferating celebrity cells.

Even so, you had your own cellular time in the sun.

You married Fantasy Island style on Fiji.

A dwarf sang ‘Sailing’ on the ukulele

as you arrived in a golf buggy,

hair blown across your eyes like multiple horizons …

My brother, proud and plump,

in ill-fitting sarong and shirt.

We had swallowed worse things than cancer’s horse pills:

the jazzy optimism of recovery statistics,

talk of the glorious sunset of remission,

the onset of broccoli-tufted hair

(our very own Jean Seberg!)

roaring you back to life

like a biblical wind in the garden.

Your new wig was pure Get Smart,

triple negative concealed.

But white-coated oncology

clashed with your bobbed homage,

the drugs only stylish to a point.

You left them behind with admirable tact.

And when the white coats looked away,

your cells grew wings

and flew you close to the sun.

We dealt with this wax-winged cliché,

chemo’s flaring, heartless conceits.

After a week the sun rolled over and turned its back,

so that the days became lightless,

faster than time. Our big familial bang –

no mere problem of science.

At the end, the sun relented,

sat poised on your bed in the middle of the night.

Its last offer: an endless chemical dawn,

your chauffeur, a morphine driver,

blurring the sounds of your children

playing in the white halls.

I’ll take it, you said.

Eventually we opened our eyes to the glare;

to an untimely pyre.

The whole family, afflicted by a kind of singeing –

like a perm gone badly wrong.

We seemed to sway as one

in breezeless, overbright corridors,

mopping heat from your limbs as if you were a saint.

Until the day came when Mary Magdalen

gestures fell hopelessly away,

and the wig was hidden quietly in a drawer.

We leant once more into strange, free air –

beyond the Fijian heat of hospital ward.

One of us, new to it, learnt how to take rings from

your cold young fingers in the morgue,

to order triangulated flower arrangements,

carnations packed in like tissues.

The pretty wig is in the wardrobe now

hanging limp after dial-a-blessing

from the Buddhist monk;

he and Shirley Bassey chanting low then loud

against the morphine’s dull lapping.

Afterwards (what kind of marker is that?)

we muttered prayers for you in a no-name park,

looking around feebly, like demented aristocrats

awaiting our own drivers

to rescue us from bloodless revolutions such as these.

Weeks on, your credit card purchases roll in,

sweetly, exorbitantly.

The new couch, smart yellow blinds,

designer chairs, sheets and towels –

a kind of second nesting

for those dear ones used to curling

about your knees like butter.

On Thursday, an expensive auburn wig

arrives in a post pack from Hong Kong.

I am fretting, feeding your children indiscriminately,

excessively.

I know nothing of Grace’s allergies.

and cannot stop this itching.

I need to speak with you, I say.

My brother, in the lemon-coloured kitchen, does not hear,

reading the bill in a halo of morning light

as if it is a love letter.

Four Sonnets

The Drowning of Charles Kruger, Fireman

(St Valentine’s Day, 1908)

Comes a fire into Canal Street:

its rows of clapboard tenements rotting back

to marsh. He knows it too well, the ‘furniture

district’. This time, a fire built on picture frames.

Charles Kruger drops onto what he thought

a cellar floor, finding instead his New World to be

eight feet of seepage bound by stone. He kicks

back to smoky air. From above come voices.

Lanterns play upon the shifting surface, sending

wobblings of light across the walls (ectoplasm

of his own trembling device) – the ghost of him

seeking release. He gives it up. Warbles out

his love. He takes the eager water: a brief

consummation made of thrashing arms.

Gustav Mahler in New York (1908)

It is the bass drum which has summoned him.

The dull collisions of felted wool against calf

skin. The end of everything, he knows, these

muted thuds.

The Mahlers have taken an

eleventh-floor suite (there are two grand pianos),

at the Hotel Majesticon Central Park West.

He joins Alma at the window. Directly below,

is the halted cortège of Charles Kruger.

Once more, the tufted mallet meets the drum

head. He sees the tight-packed waves speed

upwards, rattle through the window and collide

with his chest. He recoils. Curves his body at

the waist. A bow (conductor to his audience),

only contorted thus, gasping for air.

Mahler at Toblach (1910)

Madness, seize me and destroy me,

he scrawls across the staves. To the movement

(purgatorio)he adds a final, isolated note. Marks

it thus – ‘completely muffled drum’. At which

the four-paned windows of the häuschen burst

apart and the room fills with grey feathers.

He rises, choking. A storm of plumaged air

beating at his face. Then gone. He gathers up

the sketches from the floor. The young architect

has declared his love – (misaddressing it, he

claims, to Herr Direktor Mahler). My Almschili

he scrawls, You are not ashamed, it is I who am.

Alas, I still love you.Who finds his mouth

crammed full with soaked grey feathers.

Epilogue (1911)

Back in New York the throat infection re-

occurs. He conducts Busoni’s Berceuse

Élégiaque and returns to Europe.

Bacteria now gather at the lesioned heart.

‘My Almachi’, he cries again (again). At some

point the kidneys fail. Black water seeps into

his lungs. He drowns by tiny increments –

the death mask imparts a serenity

not on display during his final hours.

He has entrusted his sketches of the

Tenth to Alma. In the salon she tears

the most damning scrawl from the manuscript.

Carries it to the fire. Sets it to flame.

procedures in aesthetics

Bushfire Approaching

I

I am ready to evacuate if need be.

My wife emailed to say a fire is out of control

on Julimar Road, less than ten kilometres away.

She says she’ll return with the car, but I say it’s okay,

we’ll monitor and speak through the gaps.

She insists she will return: listening to the chat

in the library at Toodyay, seeing smoke in the west,

checking the FESA site. I say I will take a look outside

and get back to her in minutes. She is waiting. I climb

the block gingerly with my torn calf muscle striking back,

and see the growing pall over Julimar. A great firebreak

and a bitumen road are between here and there, I reassure,

though I will keep a close eye on it. The breeze blows

from the east, but is ambivalent and could swing

about. There are no semantics in this. And Paul Auster

is right where William (the lumberman) Bronk was wrong:

the poem doesn’t happen in words, but ‘between seeing

the thing and making it into a word’. Location location location.

As evidence: if fire sweeps through, only the mangled

metal of this Hermes typewriter will remain,

a witness, philosophy in-situ vanquished, and an elegy

made from bits of a different seeing with different words,

remain. Figurative density will take hold, and landscape

will be less fragile, the font more robust. It won’t rely

on paper: ash become an idea, a taste for some.

You stop seeing the red when it’s on top of you.

But true burning feeds on ash and the idea

of fire: it perseveres and requires only oxygen

and memory. Wild oats caught in my socks

taunt my ankles. Fuel for fire. In all seriousness.

II

I am not hearing AC/DC’s ‘This House is on Fire’

out of perversity. This morning a rush of colour

brought on a flashback, and I’ve not had one of those

for a decade. Strychnine-saturated, like the bush

where rangers claim to conserve native species

through poisoned baits. Rapid heartbeat, dry mouth,

outbreaks of laughter (grotesque, face of death),

colour codings of annihilation: spiritual and topographical.

Phantasm of acid trips – pink batts, supermen, green dragons,

orange barrels, purple hearts, clearlights, ceramic squares,

goldflakes, microdots, lightning bolts: nomenclature

of William Blake and weird melancholy of habitat loss.

Lost and unfounded. A run on images. Voices in the room.

Excruciating paranoid cartoon violence. So, I check

outside again and the plume is still moving southwest

though the wind is tentative and temperature

up five degrees over the last thirty minutes. This is realtime,

unlike hypnogogia, hallucinations? Grounds for worship.

Foundational ontology. I should mention that I have flu

and that’s why I stayed home in the first place. Harvest

is full-on though I have finished grass cutting here.

I wore myself out and my defences are down. Run down.

Antibodies hesitant if not docile. I make rhetoric

out of the flood of image-fragments: seems like good sense,

making the best, keeping a grip, cool in a volatile situation?

III

I’m abandoning my poem on the wheatbelt stone gecko

and the ‘keeled tail’ of a black-headed monitor

which is running amok through the roof, along walls,

scaling trees with maritime skill. The images lack

explanation and coalesce, are minimalist, but will

serve as a poor kind of last will and testament.

One sheet in my pocket, and it will be this.

IV

The wind has dropped, though smoke – not impenetrable

but more substantial than ‘thin’ – hangs over the block,

a tentative fallout. The birds are doing their silence

thing, or have shot through. We keep no birds in coops.

The air is almost acrid. Defend or abandon?

It’s when the smell of burning reaches upwind

that you know it has bitten deep. Firebreaks: check.

Water: check, but if the pump goes that’s an end to flow.

Fireblanket: check. Personal papers and evacuation pack: check.

No room for ‘literature’: just this poem, paperweight.

Ready to lend a helping hand: always, to best of ability.

Essential medications. Maybe the boy’s most precious toy,

but he wouldn’t expect it. Something of my wife’s.

Insects thick on the flyscreens: suddenly Hitchcockian.

V

Smoke-mushrooms are haloes about wattles they haven’t yet touched

where it counts. Prelude. Early life of devastation, its long legacy

too long in its brief moment of, well, beauty. Back again after

staggering uphill – glimpses of lush green moss amidst stubble

and granite are bemusing and bizarrely cheering – and all is suddenly

military, warzone, combat. Helitacs, fixed-winged water bombers

coming over the hills. Dousing. Or maybe it’s anti-militaristic?

No time to think about this. Three years ago, fire destroyed

forty homes just south of here. It was like this then, too.

VI

Alert Level: ‘a bushfire is burning near Julimar and Kane Roads’;

‘stay alert and monitor your surroundings’; why use quote marks?

This is barely copyright in the life and death of it. Plagiarism?

Blame burns with a heat unlike any other and burns long

after last embers have faded. And with days of heat and high

winds ahead, even a dead ember might find heart again, and leap

to the occasion. Elemental showdown. Proof. Precedent.

Test case. Habeas corpus – the body present. The burning

question: people build houses in the bush, then blame the bush.

My brother, life-long surfer, says: If I get taken by a shark

remember it was while doing something I love in its universe.

Remember me in this light. The fire has jumped Julimar Road.

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.