Cultural Studies

The Sopranos: Born under a bad sign by Franco Ricci

by James McNamara •

The Life of I: The new culture of narcissism by Anne Manne

by Anthony Elliott •

Inside the Dream Palace: The life and times of New York's legendary Chelsea hotel by Sherill Tippins

by Ian Dickson •

Always Almost Modern: Australian print cultures and modernity by David Carter

by Susan Lever •

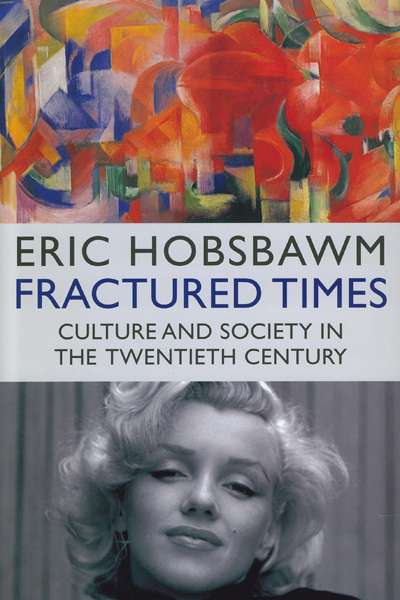

Fractured Times: Culture and society in the twentieth century by Eric Hobsbawm

by Stuart Macintyre •