Ann Moyal

The bar is set high

It was a great pleasure to read this year’s Calibre winning and commended essays in ABR. The essays written by Jane Goodall, Kevin Brophy and Rosa-leen Love continue the impressive tradition inaugurated by Elisabeth Holdsworth with her memorable work that won the first Calibre Prize. The bar is set high.

... (read more)A Woman of Influence: Science, men and history by Ann Moyal

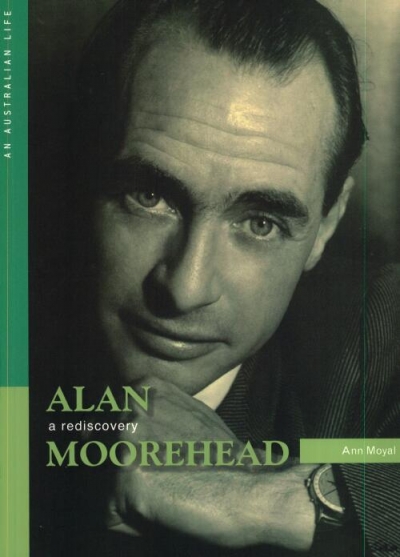

There is a timeless quality about some Australian authors that causes one to applaud when discerning publishers revive their work for new generations of readers. Wakefield Press’s reissue of Alan Moorehead’s The Villa Diana, first published in 1951, presents this fecund author’s book of essays, now subtitled ‘Travels in Post-war Italy’ ($24.95 pb, 224 pp, 9781862548459). It provides a neat introduction to Moorehead’s famous camera-like eye and his beguiling prose, which, as one commentator put it, offers ‘a long conversation that you wish would never end’.

... (read more)