Shakespeare, Sex, and Love

Oxford University Press, $44.95 hb, 282 pp, 9780199578597

Shakespeare’s Freedom

University of Chicago Press (Footprint Books), $31.95 hb, 144 pp, 9780226306667

Shakespeare, Sex, and Love by Stanley Wells & Shakespeare’s Freedom by Stephen Greenblatt

One of Angelina Jolie’s first starring roles was as Shakespeare’s Juliet in Love Is All There Is (1996). Or rather, she plays Gina Malacici, a Bronx schoolgirl fiercely protected from life by her wealthy, restaurant-owning Italian parents, recruited to play Juliet in the school play when the leading actress injures herself falling off the balcony. Faced with her fleshy lips and fricative Italian accent rich in alveolar trills on his name, Romeo (Rosario), son of the rival restaurant catering family, the Capomezzos, discovers an intense and mutual onstage chemistry with Juliet. Their respective parents’ horror is not all that mounts. ‘His dingle is getting bigger,’ mutters his grandmother watching through binoculars. ‘They’re doin’ it for real … this must be method acting,’ whisper the admiring support actresses backstage. As Juliet slowly straddles Romeo and kisses him lingeringly, the closely observed dingle attracts more attention. Paradoxically, the very public nature of theatre protects this moment of sensual privacy, creating a magic circle around the embracing couple, inviolable even by the attempted intrusion of Gina’s furious father (‘siddown fatso,’ shouts a spectator).

The film seems a world away from the traditionally tragic atmosphere of Romeo and Juliet, although, as Stanley Wells notes, even this play is ‘riddled with sexual puns, double meanings, and bawdy innuendo’. However, it does capture a central Shakespearean recognition that unruly desire will seek fulfilment against all social conventions, opposition, and proprieties. Even the restrictions of genre and the bard’s solemn reputation cannot contain an instinct which belongs more happily in comedy: ‘they are in the very wrath of love and they will together; clubs cannot part them’ (As You Like It). In Love’s Labour’s Lost,Costard ruefully confesses, ‘it is the simplicity of man to hearken after the flesh’ – and of woman, too, in Shakespeare’s world, for ‘country matters’ are just as pressing, and even the goddess of love herself, Venus, finds her ‘marrow hot’ for the reluctant Adonis. Male jealousy recurs in several plays, and although in these the man is in the wrong, elsewhere in Troilus and Cressida, King Lear, and the Sonnets, female adultery and infidelity are serious issues.The hoary convention of the bed-trick is found on inspection to be disturbingly close to rape, even when condoned by women in Measure for Measure and All’s Well That Ends Well.

Stanley Wells shows that the dynamics of sexual energy are so pervasive in Shakespeare that they can provide enough material for a comprehensive book. Virtually every work is analysed, and the resulting insights show that sex and its occasional bedfellow, love (which plays a merely supporting role), are usually the driving forces. Any ‘impediment in the current’ simply makes the river ‘more violent and unruly’ (Measure for Measure), and, like water, sexuality reaches every secret nook and moist cranny in Shakespeare’s output. Chapter headings indicate the range: The Fun of Sex, Sexual Desire, Sex and Love, Sexual Jealousy, Sex and Experience (which could have been subtitled ‘Sex in Later Life’), and so on.

Part of the reason may be that attitudes have changed. At least in the Western world, sex and violence are the most frequent matters for scrutiny by censors, whereas in Shakespeare’s time grounds for public prohibitions were politics and religion – sex was fair game. Only nudity was impractical then, since female characters were played by boys. The word ‘homosexuality’ was coined only in 1892, and although in Shakespeare’s times sodomy was a crime, ‘male friendship’ was idealised and safe. Wells seems to give more attention to gay hints than the topic may require, again perhaps because of a preoccupation in our culture rather than in Shakespeare’s.

Desire unleashes a chaotic freedom in Shakespeare’s works, as time and again he shows lovers driven by the subversive vitality of sex to flout all forces that attempt to confine their libidos, not only in the ‘wanton’ young but just as urgently in the middle-aged Antony and Cleopatra: ‘Let witchcraft join with beauty, lust with both!’ ‘Theatre is a sexy business. The relationship between actor and audience, then as now, was sexually charged,’ Wells sagely opines.

His book has one recent competitor, Pauline Kiernan’s Filthy Shakespeare: Shakespeare’s Most Outrageous Sexual Puns (2006), which the more scholarly Wells regards with distaste: ‘Kiernan’s book is a work of grotesque caricature … It is pornographic.’ His book is tastefully marked by sober scholarship and witty asides, even if the content is unnervingly similar. Wells asks, ‘How dirty-minded do you have to be to understand the play (Love’s Labour’s Lost)?’ – only to answer ‘very dirty-minded indeed’. His tone is invariably frank and sensible, and only rarely do we sense the staid English scholar loosening his tie and muttering to himself, ‘My word, it’s getting hot in here’, as he traces ‘the lineaments of gratified desire’ (Blake’s phrase) through the whole Shakespearean canon. He tries to end his account demurely and improvingly – ‘Sexual desire is but one element in the truly loving and virtuous relationship’ – but it is actually quite difficult to find a single couple in Shakespeare to exemplify this. Angelina Jolie’s Juliet seems more typical of his lovers.

‘Freedom’ in Shakespeare’s works is the theme of Stephen Greenblatt’s book too, but there is a broader liberating dimension than simply the sexual. Shakespeare continually flouts conventionality with his linguistic fertility, unique characters, and ethically problematic situations. He can subvert social norms and release into words every imaginable shade of human emotions.

Ben Jonson described his friend and rival playwright as a man of ‘open and free nature’. Shakespeare was said to be ‘not a keeper of company’ and emerges as personally self-effacing and modest, but in his imagination at least he seems to prefer a freedom which he persistently calls ‘wild’. Compulsively he undermines authority, killing off kings with impunity, mocking priests, ridiculing the pompousness of statesmen, exposing hypocrisy in rulers and idiocy in policemen. Villains and virtuous alike voice the sentiment, ‘now let not Nature’s hand / Keep the wild flood confined! let order die!’ (2 Henry IV ). Free-wheeling anarchy applies even at the micro-level of language, where ‘wild and whirling words’ (Hamlet) constantly reverberate.

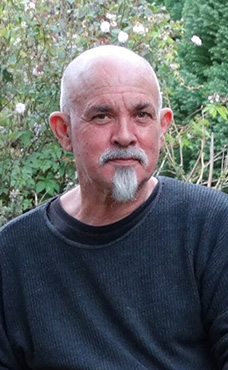

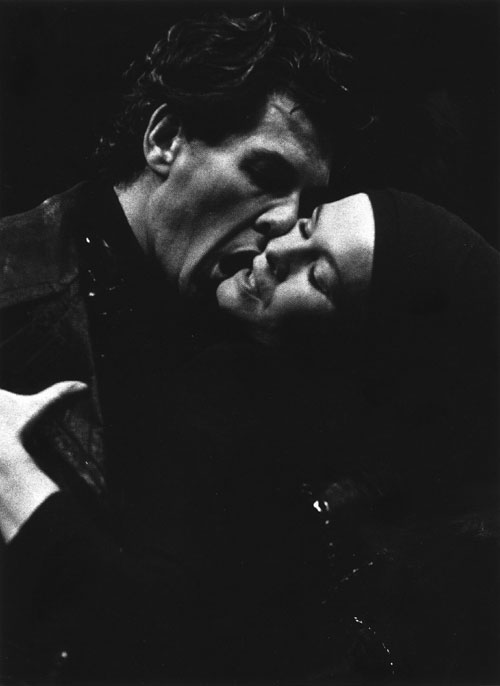

Ian McKellen and Judi Dench in Macbeth; reproduced from Dench's memoir, And Furthermore (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, $45 hb, 281 pp, 9780297859673)

Ian McKellen and Judi Dench in Macbeth; reproduced from Dench's memoir, And Furthermore (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, $45 hb, 281 pp, 9780297859673)

By coincidence, or as evidence of something in today’s Zeitgeist,a book (by an Australian) appears simultaneously with Stephen Greenblatt’s and shares the same theme. Peter Holbrook writes in Shakespeare’s Individualism, ‘For Shakespeare, giddiness is humanity’s essence’, and ‘more than any other pre-Romantic writer, Shakespeare is committed to fundamentally modern values: freedom, individuality, self-realization, authenticity’. Greenblatt’s first sentences tell the same story: ‘Shakespeare as a writer is the embodiment of human freedom. He seems to have been able to fashion language to say anything he imagined, to conjure up any character, to express any emotion, to explore any idea.’

Holbrook’s book is systematic, whereas Greenblatt’s has a more suggestive scope. It is a collection of five disparate, interrelated public lectures. The first enumerates moments when Shakespeare’s artistic freedom is manifest, and it begins a train of thought that reappears in the final essay, which argues that Shakespeare became increasingly sceptical of the possibility of the radical artistic freedom which he had celebrated in his earlier works. Another chapter shows how Shakespeare flouted contemporary ideals of beauty, with their ‘smooth, unblemished, radiantly fair and essentially featureless’ aspects, instead highlighting blemishes and stains of often bizarre individuality. ‘The Limits of Hatred’ dwells on characters in whom the perceived blemish does not damn the character – most memorably Shylock, whose Judaism in the eyes of the prejudiced Christians bears comparison in Greenblatt’s eyes with America’s view of Islam today – but it also becomes the reason why Shakespeare is magnanimous towards the anti-comic Jew’s inalienable humanity. In ‘The Ethics of Authority’, no less a professional practitioner of politics than Bill Clinton gets the essay started with his own acute observation, ‘I think Macbeth is a great play about someone whose immense ambition has an ethically inadequate object’. Beware Shakespeare’s rulers, for they all evince the same fallibility when ‘drest in a little brief authority’.

Greenblatt is always worth reading for discoveries of intriguing historical comparisons, and more often for astute attention to textual detail, cleverness, wit in argument, and entertaining style. Even though this is a short book, less than one hundred and fifty pages, it contains nuggets of gold.

These three books, read in tandem, reveal a much more vibrant Shakespeare than we ever encountered at school, and one which Gina and Rosario in Love Is all There Is would instinctively recognise.

Also Reviewed:

Shakespeare’s Individualism

by Peter Holbrook

Cambridge University Press, $170 hb, 256 pp, 9780521760676