Australian Literary Studies

A Sense for Humanity: The ethical thought of Raimond Gaita edited by Craig Taylor with Melinda Graeffe

by Jean Curthoys •

Tim Winton: Critical Essays edited by Lyn McCredden and Nathanael O’Reilly

by Delys Bird •

Travelling Without Gods edited by Cassandra Atherton & My Feet Are Hungry by Chris Wallace-Crabbe

by Anthony Lynch •

Australian Literary Studies, Vol. 28, no. 1-2 edited by Leigh Dale and Tanya Dalziell

by Brigitta Olubas •

The novel begins with the burnished quality of something handed down through generations, its opening lines like the first breath of a myth. Seductive in tone and concision, charged with an aura of enchantment, the early paragraphs of George Johnston’s My Brother Jack (1964) do more than merely lure the reader into the narrative. In these sentences, Johnston reveals the conviction and control of a master storyteller who, at the outset, establishes his ambition and literary lineage:

... (read more)Antipodean America: Australasia and the constitution of U.S. Literature by Paul Giles

by Philip Mead •

Transnational Literature: Vol. 6, No. 2 by Gillian Dooley

by Jay Daniel Thompson •

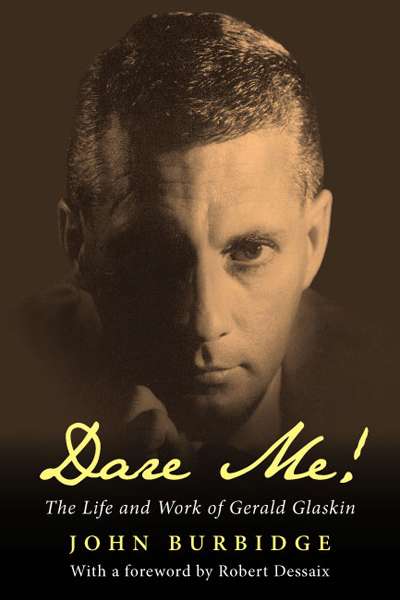

Dare Me!: The life and work of Gerald Glaskin by John Burbidge

by Jeremy Fisher •