Footprints

Fingerprints have associations of guilt, but the footprint traditionally speaks of innocence. Think of Good King Wenceslas and his pageboy, crossing the moonlit snow to deliver food and fuel to the poor:

Mark my footsteps, good my page,

Tread thou in them boldly

Thou shalt find the winter’s rage

Freeze thy blood less coldly.

Legend has it that the saint went barefoot on these nocturnal journeys. Pope Pius II is said to have walked barefoot in the snow in recognition of the ‘footprint miracle’ by which Wenceslas transmitted his radiant warmth to his follower. The footprint speaks of an innate sense of human limits, shared even by the wealthy and powerful, because it expresses a literal kind of grounding, a connection with the earth marked from childhood and remaining unbroken, no matter what more sophisticated means we resort to in getting from place to place.

I will never forget the euphoric moment on Glenelg beach when I turned to see a trail of perfectly contoured shapes left behind me in the sand. I was six years old at the time, recently arrived in Adelaide, and the only beach I’d known before was at Hastings in England, where I had to wear rubber paddling shoes to protect my feet from the bruising mess of pebbles heaped up on the shoreline.

When I revisit Glenelg now, I hardly recognise the place. There’s a marina where yachts and speedboats are moored, and the beachfront is lined with multi-million dollar real estate. These are footprints of another kind. Footprints are changing, losing their innocence as they get bigger, and their meaning is expanding, to acquire new metaphorical inflections that reflect the altered and altering relationship between the land and its human burdens.

I am drawn to this expanded terrain of metaphor. As I look out over it, all kinds of stories seem to rise there, stories from different times and hemispheres, but calling for connection with an insistency I have decided I can’t ignore. I must play the role of go-between, if that’s what I’m being called to do. But first I must do my exercises.

I check my ecological footprint online, and the results aren’t good. A terse message at the end of the quiz tells me it would require 4.6 planet earths to keep me going in my present way of life. That’s pretty much average for my demographic, but not exactly a comfortable state of affairs, so I redesign the avatar on the screen (selecting a choppy haircut and patch-pants), and set out to create a profile that will get me within the one planet budget.

Even when cheating, it takes three attempts before I get the green tick. On the first pass, I shrink the car and the house, put myself on a diet of fish and chicken, reduce my wardrobe acquisitions to a few T-shirts and cut the flying time in half. That barely comes in at the three-planet mark. I restart, adjusting the strategy from mild dishonesty to ly-ing in my teeth. After becoming a vegetarian, ditching the car for public transport and eliminating air travel altogether, I’m still on 2.1 planets. In order to squeeze into one planet, I have to downshift to a small solar-powered residence shared with three other people, get around on a bicycle and turn vegan.1

My first reaction is: do I have to? Do I really have to get rid of that much of the furniture of my mind, let alone the furniture of my life? Who’s going to make me? My conscience? Conscience pushes you into and out of all sorts of things, but it can’t be allowed to go too far. It must be balanced by pragmatism, and besides, there’s surely room for some measure of scepticism. Margins of error – considerable margins – must be allowed for, and there are still voices arguing that the planet Earth crisis may be a false alarm. This is not the first time we’ve had announcements of the end-of-the-world-as-we-know-it. The alarmists will go on ringing in our ears like tinnitus and we must neither let their noise attract our continuing attention nor ignore it completely. Well, that’s the kind of message mixture that is going the rounds in the media, but what keeps intruding itself on my attention is a cautionary tale, a story I’m somehow reminded of by the picture of that cartoon avatar whose forward march on the screen draws a boundary line round all the resources she’s using up.

The story is by Leo Tolstoy. I used to read Tolstoy when I was a student, but now I’m rather wary of his writing, especially those quietly pulsing short stories. Open them up, and before you know it, the whole universe starts to unpack. I first read this one when I was about eighteen, and certain images from it are permanently lodged in my mind. James Joyce called it ‘the greatest story that the literature of the world knows’. Its title, in literal translation, is ‘How Much Land Does a Man Need?’ That’s really not a very good title, I’m thinking, as I find the page. Fiction should not wear its moral messages on its sleeve, and what’s more it should pick messages that are subtle, unusual or incisive, and not proposition its readers with slogans. All the same, fresh from my experience on the website of the Global Footprint Network, the question had a certain ring to it. How much land does a man need? The GFN could answer the question instantaneously: 1.8 hectares of bio-productive land. Well, that’s how much there is to go round, from a planetary point of view, and from a biological point of view, a human life should be sustainable on that measure of the earth’s resources.

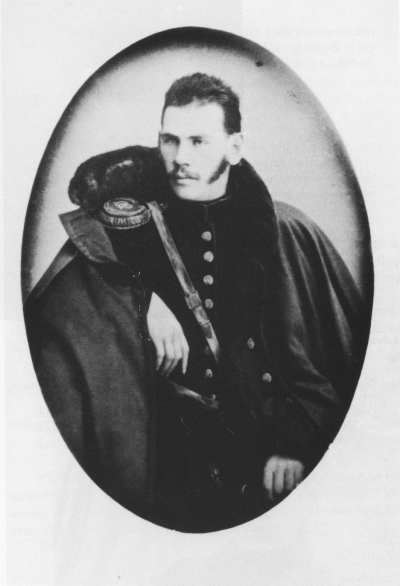

Leo Tolstoy, 1854

Leo Tolstoy, 1854

Tolstoy’s narrative opens with an argument between two sisters. One is a peasant’s wife living on communal pasture; the other has moved to the town and is boasting about life in fashionable society. It’s the age-old stand-off between the town life and country life, the world of traditional sufficiency and the one filled with novelty, style and indulgence. The peasant’s wife cuts off the discussion with an old proverb. ‘Loss and gain are brothers twain.’ Then her husband, a man called Pahom, who is taking his afternoon rest on the stove-top, mutters a background comment of his own. Life on the land is fine, if there is land enough. ‘If I had plenty of land, I shouldn’t fear the Devil himself.’2 But the devil, who happens to be loitering in the hot air behind the stove, also overhears, and the story shifts gears. The received wisdom of a trite folk tale is about to take on metaphysical proportions, with a sinister edge. And the size of the human footprint is precisely what is at issue. Just how precisely is a matter for only the devil to foresee, and his design unfolds gradually.

The peasant’s family is part of a commune, sharing a small herd of animals on an inadequate expanse of pastureland, but a few months after the opening scene of the story, there is an opportunity to buy some land independently when a local estate is being sold off. Pahom successfully puts in a bid, and his first taste of land ownership is expressed as a poor man’s epiphany. ‘When he went out to plough his fields, or to look at his growing corn, his heart would fill with joy. The grass that grew there and the flowers that bloomed seemed to him unlike any that grew elsewhere.’

These are good feelings, and people of good heart would surely warm to them, but so does the devil, who is no longer skulking but energised and on the move, stirring up the neighbourhood. There is wrangling about boundaries and encroachments. There are frustrations, problems to be solved, and, as the devil knows, the road to hell is paved by problem solvers. He pays another visit, in the guise of one of the new breed of traveling real estate brokers. There’s a place further up the river, he reports, where land is going cheap. Actually, it’s a long way further up. Pahom takes the steamer as far as it goes, but still has to walk three hundred miles to the destination. If you want to enlarge your footprint, don’t you always have to go abroad? Isn’t this how the global economy came about in the first place, through the geographical outreach of venture capitalists? But this is no story of sudden transformations. Tolstoy lets time as well as space stretch out in his narrative. It’s a case of one thing leading to another, and, of course, removal to the new pasture-land is not the end of Pahom’s journey, or of his story, or the devil’s doings, which create trouble in the neighbourhood of just the same kind as before, so that, just as before, the landowner must solve his problems by moving on, to gain more expanse and better control.

The opportunity this time has a certain romance about it. It involves a frontier adventure in the remote steppes near the southern border of Russia, where the Bashkirs have been persuaded to sell some of the vast tracts of prime pasture-land over which they have traditional ownership. Being nomads, so the rumour goes, the Bashkirs don’t value the land, and are amused to find that people are prepared to give them money or valuable goods in exchange for it. Pahom’s journey takes him up the River Samara, a tributary of the Volga, into the region where Tolstoy himself, in a state of mid-life restlessness and depression, went to buy up land in the early 1870s. The wraiths of the author’s conscience hover about this phase of the story, for Tolstoy, unlike his simpler protagonist, never got the better of conscience, which may have restrained his approach to the bargaining process so as to avert the fatal consequ-ences towards which Pahom is making his way, like some cheerfully oblivious alter ego.

During his journey, Pahom collects a few luxury gifts of the kind he thinks might appeal to the Bashkirs, and mentally prepares for a bargaining process in which his goal is to get as much as possible for as little as possible. On his arrival, he is entertained with high good humour by the Bashkirs, who tell him that the price of their land is one thousand rubles a day. He doesn’t understand. One thousand rubles, they explain, for as much land as a man can get around in a day, on foot, between sunrise and sunset. At dawn, the Bashkir elders will gather at the agreed starting point and remain there until the sun is at the opposite horizon line, to seal the bargain. The purchaser leaves markers as he goes, and a ploughman follows on to create a boundary furrow between them. Over a restless night before the crucial day, Pahom calculates that he can walk about thirty-five miles between dawn and dusk, which should equate to around 150 acres. That’s one big footprint. For Pahom, at last it will be enough.

At sun-up, he sets out from the starting line at a robust though steady pace, but as the sun rises higher, enabling him to figure out the lie of the land, he is prompted to go more briskly. There is a wooded hill that he can take in, and a valley, perfect for growing flax. From every vista, visions arise in his mind of the future abundance that will grow there, but his body is sending other kinds of messages. It’s getting hot. He’s taken barely any food or drink, and his feet hurt. Stopping briefly for a rest on the rise of the hill, he sees the elders gathered round his goal-point, so far away that they look like ants.

Pahom’s home run is a gathering nightmare, as the distance towards the finishing post stretches out in front of him, while the sinking sun closes on the line of hills at a rate he cannot match. Drenched in sweat, lungs ‘working like a blacksmith’s bellows’, he suffers a massive heart attack. The chief of the Bashkirs takes up a spade to mark out all the land their ambitious customer will now require: a six-foot grave plot.

There’s something primal about the theme of over-reaching our properly delimited claims on the earth. Yet how do we draw the limit? The 150 acres, or sixty hectares, Pahom was targeting in his last run would, in the current economy, serve to maintain four residents of one of Sydney’s wealthier suburbs in the style to which they are accustomed, but the distance between these two situations in conscience and consciousness is hard to measure.In the urban landscape, our feet are rarely on the ground in the true sense, since the lie of the land has been transformed by architecture and engineering. As Paul Carter puts it, ‘many layers come between us and the granular earth’.3 Pahom is right there in the primal space, caught between sun-up and sun-down, between the limits of his body and the reach of his imagination.

His story illustrates, amongst other things, the genesis of economic consciousness, which is sometimes confounded by the very principles of measurement out of which it is born. In taking the measure of things, systems of calculation come into play, but there may be strange incommensurabilities between one system and another. The Bashkirs evidently had a shrewd grasp of the principle of incommensurability. One thousand rubles a day. It’s an equation that taxes the economically literate mind by confusing the primary principles of time and space. Money is what brings them together, but not money alone. This is not a rental agreement. Something besides money is on the line, and in this case it is a human life: heart pumping, blood circulating, lungs drawing in and pushing out, feet on the ground. Eyes on the prize. Motion and motivation create another equation that crosses between dimensions. That they should be brought into collision with such finality, and with the animal physiology of motion deciding the matter over and above the most highly charged determinations of the will, is a shock to the system. But whose system? Certainly not that of the traditional owners, though their bargaining strategy may well have saved them from an exchange with fatal consequences to their way of life.

Here is a view of economic acquisition and indigenous occupation as two radically incompatible forms of relationship to the land. In this instance, the Bashkirs manage to turn the culture of acquisition, with all its fatal momentum, against itself. These nomads,bemused by the fixations of boundary-minded foreigners, evidently have some mischievous inkling of how the boundary is a weapon that can cut both ways, and have found a tactic for controlling its deployment. They have devised a trick for delimiting the footprint of economic man, though it must be said that the trick can only work in a situation where some formal bargaining approach is made.

In Australia, under the principle of terra nullius, stories of traditional ownership and economic acquisition pan out quite differently. We can mark the very day on which economic consciousness entered the relationship between this land and the human species: 29 April 1770, the day of James Cook’s first landing at Botany Bay.Cook’s journals testify to a world known by numbers and quantities. He records the longitude and latitude of the Endeavour’s positions, the depths of the sea around it, the wading distance to the shore, the sun’s meridian, the time of the moon’s rising. Details about the weight, with or without entrails, of two stingrays that have been caught evidently interest him less. He crosses out the statement, leaving the numbers blank. It is the task of Joseph Banks to know the particulars of what lives and grows in the environment; Cook’s responsibility is technical orientation. Schooled in the most advanced disciplines of measurement available in his time, the measures he needs to take are those of the land itself, in its larger global setting, and by doing so he enables its possession as a whole, within the system of empire. In his adventuring, Cook set the bounds of empire wider than any human individual before him. As a recent biographer puts it, he ‘twice put a girdle round the earth’.4

‘In his adventuring, Cook set the bounds of empire wider than any human individual before him’

Once settlement gets underway, the scale of the story downshifts and the narratives start to multiply. Fiction exploits the licence of memory, individual and cultural; through deepening story lines, memory harks back to a state of innocence, then becomes heavy with the loss of it. At the innocent end of the spectrum is the semi-autobiographical We of the Never Never (1908), which chronicles the lives of the settler community on the Elsey, one of the largest cattle stations in the Northern Territory. The recollections are those of Mrs Aeneas Gunn (Jeannie Gunn), a model of pluckiness, in whose eyes the blackfellas around the homestead are a jovial community of willing helpers. She expresses an ingenuously reasonable view of their rights: the white man has taken their land – for which the justification is tactfully assumed, without elaboration – but they should be free to come and go on it, and to take whatever essentials are required for their simple way of life. The white pastoralists are lucky to have their own needs met. Food, fuel and shelter are hard won, and their situation is an ironic reversal of the conventional equation between expanse and affluence. This cattle station extends over a million and a quarter acres, so the process of working it involves arduous journeys out into ‘sun-baked, crab-holed, trackless plains’. The front gate is forty-five miles from the house and 130 miles to the next outpost of human habitation. In these circumstances, the containment of a modest homestead is welcome and ultimately, as Jeannie Gunn records (without any need to associate herself with Tolstoy), ‘“enough bush to bury a man in” … is all these men of the droving days have ever asked of their nation’.5

In February 2000, a native title claim for Elsey station was settled on behalf of the traditional owners, the Maharri people, and the area with its township of Mataranka is now under the governance of the local community. Its history has not been untroubled by disputes, but the Mataranka website invites visitors to the Never Never as ‘genuine frontier country, a wilderness area untouched by development’.6

We of the Never Never has acquired quasi folk-tale status, and has a counterpart in Nevil Shute’s A Town Like Alice (1950), a novel set in a similarly remote place just across the Queensland border and also concerning the experiences of a young white woman facing the challenge of life on a cattle station. The two books sit in company with each other on the shelves of the airport newsagent in Alice Springs, as essential reading for those on the outback touring circuit. That’s in fact where I bought my own copies, and I read them in the air-conditioned cafés of Alice, between swims in the hotel pool. It wasn’t doing my eco-footprint any good, but who wouldn’t want to spend time in that way, in a place like that? It’s the life Jean Paget in Shute’s story dreamed of creating for the white women of outback Australia, and she would have added a few extras to my scene of indulgence: an ice cream soda, a trip to the hairdresser, lotions to cool the skin, and a new pair of shoes in the finest crocodile skin. Restrictions to the footprint were not anywhere on Jean Paget’s agenda.

Her story begins two generations later than Jeannie Gunn’s, and she arrives by plane in the Gulf country of north Queensland, bringing with her a recently inherited legacy and several years’ experience as a secretary with a London shoe-making business. Not about to resign herself to a life of hard labour and material deprivation, she immediately sets out to reform the conditions she sees around her, especially those in the local town. Willstown (a fictional place based on Burketown) is a former gold-rush settlement that has been steadily depopulating. Writing home, Jean reports on a set of negatives: there is no cinema, no dress shop, nowhere to buy a newspaper or an ice cream, no radio to listen to, and no supply of fresh produce. The store trades in dried peas, hardware and all-purpose cleaning fluid, and the only entertainment is lighting the aura of gas around the spouting artesian bore in the main street. Women will not stay in a place like this, and the men lead arid bachelor lives.

Jean has visions of turning Willstown into a flourishing town like Alice Springs. She will establish a small shoe-making business to exploit the local availability of good alligator skins, with employment for half a dozen young women. And there must be an ice cream parlour so that they will have somewhere to relax and spend their earnings. A shrewd businesswoman, Jean has no trouble turning these visions into reality. Before long, the shoe factory has doubled its staff and the ice cream parlour has diversified into an all-purpose centre for female indulgence, selling cosmetics and fashionable clothes in addition to the treats served at the glass-topped tables. Air conditioners are installed, and large refrigerators. Machinery proliferates in the factory. At this point, Jean decides they also need a swimming pool, one with diving boards and change cabins, surrounded by irrigated lawns. At ‘a bob a bathe’, it can’t fail to be a going concern.7

In A Town Like Alice, commodity culture sprouts with shining innocence, as a form of community benefit. The novel is, unwittingly, also a chronicle of the advancing ecological footprint, impelled by the needs and desires of white women. Such a view is of course one-sided, and somewhat sentimentalised. As a portrayal of settler culture, it is oblivious in relation to the bigger picture, which soon begins to show itself in a town like Alice.

It doesn’t take long to realise that the place harbours two economies, their separation marked by the parallel lines of the Todd Mall and the Todd River. The river is dry most of the year, and its sandy bed is where dozens of Aboriginal people sleep and hang out. The cafés are the whitefella hangouts – blackfellas don’t go in them. Sitting in one of those cafés, with my book in front of me, spooning the froth off a cappuccino between paragraphs, I looked out through the tinted window onto the mall as a group of blackfellas cruised past with their dogs, and was overwhelmed by some feeling I couldn’t identify. Guilt would be an obvious label for it, but it was something more physical, a sense of being bodily out of place, or more than that, I felt almost as if I wasn’t there at all, was not a presence in this place, just some random projection, teleported in a glass capsule with the material attachments of the book and the spoon.

Towards evening, I walked out across the riverbed, taking off my shoes so I could feel the sand under my feet. I wasn’t sure I should be walking there. I was not at all sure I had the right. This was a place of dreaming, and if you are going to tread on dreams, shouldn’t you at least have a Wenceslas to lead the way, an elder who knows about crossing over between one human world and another? But the culture I belong to doesn’t have elders like that any more. I had to watch where I planted my feet, because there were things in the sand. Cigarette packets, cans, broken bottles, food cartons, the odd shoe: scatterings from the supply lines tapped into the town economy. Leakage from an open wound, where another kind of lifeline has been torn away.

An Aboriginal woman was sitting on the grass watching me as I approached the opposite bank. She beckoned me over, evidently quite relaxed about my being there. She wanted to sell me a painting, for $15. It’s the going rate for small freshly painted canvases sold on the streets around the town. ‘This. River. Women’s Dreaming. This here. The women.’ She points to a row of shapes like half-curled caterpillars arranged beside the wavy line of the river. Those contained outlines of the women’s presence, one of the most familiar symbols in Aboriginal art, say something about how human beings keep to scale in indigenous tradition.

For Australians outside this tradition, ours is a country of confused outlines. Kate Grenville’s The Secret River (2005) begins with a night scene from early colonial life near Sydney. A man stands in the doorway of his hut, a structure in which there is ‘hardly a door, barely a wall,’ and looks out into the textured darkness. He fears the encroachment of its silent natives, with their gift for camouflaging themselves in almost any conditions of light and darkness.8

William Thornhill is a freed convict who later plans to move his family to a patch of land on the banks of the Hawkesbury, where he intends to make a living. At the end of the novel and after a passage of many years, this same man is on the verandah of his fine house at sunset, surveying the land through a telescope. He owns three hundred acres now, and has a piece of paper to prove it. His boundaries are firmly marked, and fenced. The new house is sturdily built on a European model, with lockable doors. There are high walls round his garden and a fine pair of gates guarded by imported stone lions. Still, though, the land around him refuses to settle down into any kind of perspective. Through the telescope, its scale is delusory, and it wobbles like a mirage in the angled light. Thornhill knows there is something wrong between him and the land. It belongs to him but he doesn’t belong to it.

That the land itself is the senior partner in any transaction for ownership is a principle that those in the settler economy can’t afford to understand, but it has ways of coming home to them. With The Secret River, we’re back in the primal scene of land ownership, a scene in which the psychical ingredients of Pahom’s experience are replicated. The hemispheres of the globe don’t keep these experiences apart. It’s as if they are always there, lying low in the landscape, waiting to claim some human unwary enough to go out there looking for property.

It all starts quite innocently – apparently – stirred by the breath of free enterprise, driven by the problem-solving imperatives that accompany any bid to make a sustainable living from scratch. In this case, the scratching is a simple form of tillage, so that corn can be planted, and signs of tillage are the first signs of a land claim on whitefella terms. In the absence of fences or other boundary markers, one of the initial problems is the difficulty of telling whether a particular tract of riverside land is free to be ‘taken up’.

Once he’s determined that there is vacant possession on his chosen patch, Thornhill starts the transactions for occupancy: money is obtained on a loan, a deed of purchase for a hundred acres is signed, a bigger loan is negotiated to cover the purchase of a trading boat. All this will have to be repaid, through labour and industry. The line of acquisition is being fed out as the vision expands, but the point of closure must always be kept in view. Thornhill has a limited time frame for closing his deal, so the clock is ticking and he must work at full stretch to return the sum within the period of agreement.

Tolstoy might have seen him as having already contracted with the devil, but for the first twenty four hours he feels like Adam before the Fall, revisited by the innocence of the world itself. This place is his own, he realises, ‘by virtue of his foot standing on it’. In his moment of epiphany, he echoes Pahom’s luminous sense of connection to all that he sees: the grass, the blackbird, the sunlight, even the mosquitoes. Later, as he lies down to sleep, the sense of elation expresses itself as a new calm. ‘To be stretched out on his own earth, feeling his body lie along ground that was his – he felt he had been hurrying all his life, and had at last come to a place where he could stop.’ Here, ‘stop’ means a number of things other than the physical process of coming to rest. It means a stop to cravings and hankerings, to those dissatisfactions and deprivations that give rise to the unrelenting sweated labour of mind and body.

Stopping in such a way – arresting the gathering momentum that ultimately drives Pahom to his death – is a transient experience for Thornhill, a moment of equilibrium that is not sustainable. On this thought, I want to stop also, between the two stories, for long enough to catch another thought that needs to be approached from a particular direction: a thought about ‘sustainability’, which is a word so overused in the current climate change debate that it is threatening to blank out on us. It’s a policy word, relating to strategies, resources and technologies, and it carries with it a corporate approach to conscience and behaviour management.

‘The quest for sustainability has to get outside the dynamic of problem solving if it is to avoid defeating itself in a mess of hustling intentions’

Something’s missing here. The quest for sustainability has to get outside the dynamic of problem solving if it is to avoid defeating itself in a mess of hustling intentions. You don’t have to believe in the devil as a cloven-hoofed domestic intruder to get at the depth-charge that is planted in the short story about how much land a man needs. The mischief at work in the scenes of Pahom’s downfall is a busy principle that also has a secular face. From a social and economic point of view, it is not mischief at all, but good behaviour. As Thoreau says, after dropping the burdens of middle-class life to make his retreat to a fifteen-by-ten-foot hut beside Walden pond, ‘Whatever possessed me that I behaved so well?’9 For the last couple of decades, most of us have been behaving too well as ‘the economy’ has demanded more and more of us, pushing the imperatives of growth, profit and escalating work rates to a new peak of intensity and characterising anyone who didn’t get on board as ‘resistant to change’. It takes a very special order of consensual stupidity to allow slogans like that to rule the channels of public communication, and we surely have to recover from consensual stupidity before we can really start recovering from ecological delinquency.

The starkly simple question underlying the buzzing business of sustainability is, can we stop? Not, can we make this or that last in our systems of energy and commodity supply, but can we stop, we the human species, with our needs and wishes and anxieties and problems? Such a proposition is beyond the reach of policy-making and serves, perhaps, as a reminder of why we need literature. Or at least, stories.

Kate Grenville (photograph by L. Graham)

Kate Grenville (photograph by L. Graham)

To return to The Secret River. Grenville’s narrative plants the dynamic of acquisition in a social world, where the motivation of the individual tangles with the determinations of others, which is how Thornhill is dislodged from his brief experience of equilibrium. There is no clear outline to Thornhill’s share of responsibility for the horrific debacle to which his enterprise leads. On one side of him are fellow settlers with whom he can establish the beginnings of a trading network. Good relations with them are vital to the survival of his economy, but there are some rocky temperaments amongst them. On the other side are the indigenous inhabitants. Although indigenous ownership of the land is factored out of consideration by the new settlers, the Aboriginal presence raises boundary questions of several kinds. First, there is the anxiety of who has been digging over the soil in the midst of Thornhill’s chosen patch, and here the fatal trail of problem solving begins. Both he and his wife Sal attempt some dialogue across the racial divide, she more effectively than he, as a group of Aboriginal women establish a relaxed activity zone near the hut, and begin to offer their bowls and digging sticks in exchange for portions of sugar. It is the white men, though, who decide the terms of engagement. Stories are exchanged about the bloodthirsty cannibalism of the blacks, and the acts of atrocity they are liable to commit at any opportunity.

Where there’s room for interpretation, there’s scope for paranoia, and paranoia has some strangely essential relationship with the acquisitive mindset. ‘Loss and gain are brothers twain,’ as Pahom’s wife says at the beginning of the fatal adventure. Gain is inevitably accompanied by a nagging sense that the world is owed a loss – and may be plotting to take it, through the agency of who or whatever is conveniently available. Grenville is especially good at stalking the operations of paranoia in the early colonial environment, where land acquisition is accompanied by violent imaginings that are stirred up in every conversation about ‘the blacks’. In the absence of physical boundaries, anxieties about encroachment or invasion are ever-present; interpreting the movements of the blacks becomes an increasingly fraught process. A crisis point is reached as the Aboriginals gather for a corroboree and start to pound the earth with their dancing. This happens in the section of the novel that Grenville entitles ‘Drawing the Line.’

A fence must be built around the hut – more than a fence, a barricade – but there is no keeping out the paranoia, surely the most dangerous of all human demons, and lines of personal determination converge on the inevitable catastrophe. There is a massacre, as brutal as anything in the annals of human brutality. Afterwards, a kind of calm sets in, a synthetic version of the equilibrium Thornhill knew so briefly. His future extends through phases of growing prosperity, but there are scars in the lifeline now, stretching out into future lives in the growing economy of the colony. In the last scene of the novel, before he takes up his telescope to survey the scene, Thornhill watches an old blackfella smoothing the dirt with the palm of his hand and, in the second epiphany of fallen nature, realises that his own connection to the earth has been lost.

White Australia has at last apologised for the abuses in its history, but where do we look for a model of sustainable coexistence between indigenous economies and those of industrialised commerce? The very measures taken by fuel-guzzling nations to reduce their carbon footprint have been directly instrumental in reducing the food supply and escalating the price of essential grains in parts of the globe where food is all people can afford. Sustainability is one of the hallmarks of many indigenous economies, but it cannot withstand the dynamics of economic growth and industrial development. In his recent book Blessed Unrest (2007), Paul Hawken makes an inventory of local indigenous economies jeopardised by specific industrial enterprises, with examples from Borneo, Nigeria, Colombia, Guyana, Honduras, Chad, Botswana, Chile, Morocco, Brazil, Norway and Australia.10 The secondary damage knows no bounds, as climate change spreads the impact of global enterprise throughout the natural world.

‘White Australia has at last apologised for the abuses in its history, but where do we look for a model of sustainable coexistence between indigenous economies and those of industrialised commerce?’

While the boundary line is one of the founding gestures of a culture of acquisition, this culture in its most advanced forms has become fiercely intolerant of boundaries, reconceived as ‘trade barriers’ for protectionist enclaves. The acquisitive life eventually leads beyond all bounds. There is no stopping it. Notions of global free trade have taken over the airwaves with a heady aura of unbounded possibility, yet the globe itself is a circle, that most ancient and potent of boundary lines. Plant a foot in it, and you are grounded in the materiality of a physical world that is incommensurable with the figural space of economics.

When William Rees introduced the concept of the ecological footprint in a book co-authored with his research student Mathis Wackernagel in 1996, he must have been aware that he was attempting nothing less than to bring two orders of reality into a common analytical framework.11 Rees, a professor of environment and resource planning at the University of British Columbia, had been modelling the ecological footprint in his lectures, to illustrate the principle of ‘carrying capacity’: the number of individual humans a specified area of land can support. Extrapolate this principle to a whole-earth scenario, and you have a stark picture of the ultimate budget.

A cognitive switch is being thrown here, though the logic is disarmingly simple. If you calculate the average human footprint, in terms of how much bioproductive land is required to support individual consumption patterns, then multiply this by the number of people in a particular city or country, you can see how far their earthly support base extends outside their actual dwelling zone. The Netherlands (one of Rees’s textbook examples) boasts an agricultural surplus, in spite of the density of its population, but this is sustained through the importation of fodder for livestock. The fodder is grown over an area several times larger than the bio-productive land base within the country, which is used to turn the low value animal food-stock into high value human consumables such as cheeses and processed meats. As Rees puts it, ‘the Dutch don’t live in Holland’.12 Suddenly, an economist’s picture of successful overdrive flips to a deficit model.

On the same principle, the urban powerhouses of the world’s major industrial economies are all deeply in ecological deficit. Cities are human feedlots, whose maintenance requirements stretch over vast tracts of land that most of their inhabitants will never even see. In an urban society, cultures of consumption are governed by monetary exchange. Money is what the urban consumer is immediately, and sometimes exclusively, conscious of having consumed, and ‘budgets’ mean financial outlays within funding limits. Budgets can always be expanded, however, in an indefinitely expanding economy. The sub-prime crisis in the United States was created by the consensual delusion that when money runs out, debts can be converted into assets and sold off on the stock market, where they are reported as profit.

There are no footprints in economic hyperspace, only incessant trans-global movement that defies the gravitational pull of the earth’s body. It is our money that’s running away with us, spinning out a dizzying array of manufactured wants that undergo rapid cultural conversion into needs and essentials. At the level of the individual, there is the debt burden, beginning as an expansionary adventure, in which the progressive stages are marked by the leather lounge suite, the plasma television, the car and the mortgage. As the repayment schedule forces an ever-accelerating rate of work, anxiety begins to chase euphoria, and the point of closure once dreamed of becomes a point of foreclosure. At the corporate level, the company builds its value through a program of strategic borrowing strategies, which enable a succession of takeover bids and an escalating schedule of profit reports, until the schedule of returns begins to fail, the superstructure of traded debts implodes, shares tumble and wholesale debacle becomes inevitable. The same essential pattern is now showing up at the level of the species: acquisitive habits drive us to create an ever-expanding footprint on the earth, but the earth has its own reckonings and we have too blithely assumed we could negotiate them. Suddenly we are aware of a tipping point, and our almost certain incapacity to head it off by reining in the boundary line. How much consumption will fit into one planet? Finitude must return to economics.

‘Downsizing’ is a response to this imperative, but compared to the up-scaling imperatives built into our major national economies, downsizing will remain a weak and uncertain dynamic unless it is infused with a new kind of cultural energy. Rees is concerned about how such energy might be sourced, and suggests that the heart of the problem ‘is the fact that people today rarely think of themselves as biological beings’. Perhaps if we had physically to perform the run around the boundaries of our ecological footprint we might be reminded, but the kind of running we have to do to keep up the supply lines for our expenditure puts a different kind of strain on us. Mental stress has physical repercussions that, typically, we don’t see coming.

The psychological euphoria of acquisition is countered by states of bodily dysphoria. Loss and gain are brothers twain. But while the euphoria takes over certain localised areas of the brain, anxiety pervades the whole being, generating symptoms that are just as sure a recipe for heart attack as a mad dash across the landscape in a state of acute dehydration. Acquisition is a drug, and there are social and personal predispositions that cause us to crave it, but there’s a paradox: as physical beings, we don’t like it.

Cultural evolution in the developed world hasn’t made us too smart about negotiating the terms for our physical existence. How much have we gained by swapping hunger for eating disorders, heavy labour for heavy liability, overworked muscles for hypertension, inadequate housing for overwhelming mortgage stress? Maybe the balance sheet is in our favour at the negative end of the spectrum – let’s not underestimate the privilege of being in an economy that makes death from starvation or exposure a rare phenomenon – but what about the positive end? The continuing appeal of Thoreau’s Walden has much to do with its infectious euphoria, as Thoreau invokes the pleasures of watching the changing light, of a dinner made from fresh caught fish or hand-reared vegetables, of warm fire after a cold walk, of letting time pass in meditative calm. After rereading this book, it occurs to me that the escalating concern about climate change amongst the general public may have something to do with a deep-seated component of human nature that actually craves the dismantling of much of the economic superstructure of our lives, and that is resistant to change in a way never envisaged by the phrase-mongers of the commercial world. What we like and don’t like aren’t always coherently realised in our own minds, especially when those minds are not tuned in to our bodies.

In the late 1980s, a young college student from Emory University in Atlanta was reading a heady cocktail of stories: pieces by Tolstoy, Melville, Gogol, Jack London, Pasternak, laced with shots of Thoreau. Friends became alarmed as they noticed spartan changes in his lifestyle. The furnishings of his room were stripped back to a thin mattress and a couple of milk crates. After going through his graduation ceremony in May 1990, Christopher Johnson McCandless wrote a cheque to Oxfam for some $24,000 (what remained of the sum bequested to him for his education) and went on the road.

What McCandless wanted was, in economic terms, next to nothing – a footprint just large enough to keep body and soul together, somewhere in the Alaskan wilderness. He arrived at his destination at the end of April 1992, after hitching a ride out of Fairbanks, and found shelter near the foothills in a derelict bus, stationed there by the Yutan Construction Company as temporary shelter for workers employed to upgrade the trail. McCandless cleaned up the interior, made himself a bed and a writing table, and survived there for 112 days on a diet of berries and small wildlife, keeping a diary in which he recorded the moods, challenges and inspirations of being alive in the wild. The last entry was a desperate plea for help, as he succumbed to the terminal stages of starvation.

Emile Hirsch as Christopher Johnson McCandless in Into the Wild, directed by Sean Penn (Paramount Pictures, 2007)

Emile Hirsch as Christopher Johnson McCandless in Into the Wild, directed by Sean Penn (Paramount Pictures, 2007)

The discovery of his body two and half weeks later made a small item in the newspaper, with just enough detail to arrest the attention of John Krakauer, an adventurer himself, and a journalist. Krakauer made further investigations into the story for Outside magazine, which published his 9000-word article on McCandless in its January 1993 issue. The response was unprecedented, and fiercely divided. One way or the other, this was a narrative that got a grip on people, and there didn’t seem to be much middle ground in the spectrum of reactions. At one end of it were readers – many of them Alaskans – who castigated the young adventurer for his narcissistic delusions about the wilderness experience; at the other were those who found the story inspirational. Krakauer himself admits to something of a fixation on the McCandless case, and developed his article into a book, Into the Wild, which was published in 1996, and subsequently made into a film by Sean Penn.13

The film tells the story with mature ambivalence, as a romance of the spirit and a physiological tragedy. In the opening sequence, McCandless gets out of the car in which he’s hitched a ride to the start of the Stampede Trail, which he plans to follow into the remote landscapes across the Teklanika River. He accepts the driver’s gift of a pair of rubber boots, and the camera pans back to show him striding out across the pristine surface of the snow, leaving a trail of footprints.14

McCandless’s tragedy was that he couldn’t make a large enough print. Day by day, in agonising degrees, his body shed weight and muscle as he failed to supply it with a subsistence level of nourishment. He fought hard for survival, using all his skills and his wits, fighting at the same time to sustain the vital joy of being alive. Sustainability eluded him. He’d found a place to stop, but he couldn’t stop the process of natural attrition that got him in the flesh.

All the same, he left his story, and that just seems to keep on spreading. A sign, surely, that it touches a raw nerve. Conscience stirs. Shouldn’t we all be doing something like this with our lives? If we don’t, can we really say we’ve been alive, woken up to the world, measured our being against the vitality of the planet? On the other hand, should McCandless have had more concern for his family and friends, been more realistic about social dependency, been more competent and hard-headed about the business of survival, in which poetic awareness can become a hazardous distraction?

Should and shouldn’t go into a tailspin and conscience starts to eat its own entrails. Whatever possessed me that I behaved so well? The argument in the head is as incessant as that in the public sphere, and with all that noise going on, how are we to concentrate on the business of getting the footprint right? That, after all, was what Tolstoy and Thoreau, and their disciple McCandless, were actually trying to do. None of them offers us a model we can copy. Tolstoy became a censorious recluse. Thoreau cheated by conducting his subsistence experiment on what was ecologically a five-star billet, with rich soil, fresh water, abundant timber and enough fish and small game to provide good dinner menus all year round. McCandless starved himself to death socially as well as biologically, and if the second of these outcomes was a tragic error, the first resulted from an entirely deliberate refusal of co-dependency.

Even so, their stories call, and it’s the calling that counts. Models can lead to imposition, and humankind has a poor track record when it comes to imposing mandatory forms of equity and economic limitation. How could we even contemplate it, after what happened in Russia and China under communism? Not to mention Czechoslovakia, where the statue of St Wenceslas in Prague Square has looked down on too many scenes of imposition, and too many horrors arising from attempts to protest them.

What is needed, according to Václav Havel, in his extraordinary opening address to the international delegates at Forum 2000 in Prague, ‘is for something to change in the sphere of the spirit.’ The only way ‘to stop that blind perpetual motion dragging us into hell’ is ‘an existential revolution.’15 Havel is one of the few voices in the current debate to insist on the metaphysical dimensions of ecological thinking. He speaks from a tradition of Czech philosophy that calls for a return to the natural world as a world of primary experience, through which humanity can be reconnected with ‘a vital sense of good and evil’.16 In order to fend off planetary devastation, some authority other than that of the political or social order must be brought into play. ‘We must revise not our procedures but our view of reality. We must subject ourselves to an authority now ignored – of real persons in their life world.’17 There is no political machinery or green technology to assist in promoting this appeal.

‘Havel is one of the few voices in the current debate to insist on the metaphysical dimensions of ecological thinking’

The statue of St Wenceslas is mounted on a charging horse, high above the square in the centre of Prague. This is not the barefoot, grounded elder celebrated in the English carol. From his vantage point, he’s seen the capital development that made the Square into a headquarters for banks, hotels and stores; the bombardment that destroyed many of these during World War II; the communist putsch of 1948; the festivities of the Prague Spring in 1968 as the constraints of communist censorship were loosened; the Soviet tanks rolling in, to reinstate the controls with a vengeance. And one day, in the depths of the following winter, practically at the feet of the sculptured figure, twenty-one-year-old student Jan Palach set himself alight in a suicidal protest against the occupation. Here was a youth for whom the saint’s magical protection didn’t work. Wenceslas has lost his innocence, and the only elder whose voice can be heard is that hoary old demon conscience, which, as Havel proclaimed to the US Congress, is in charge of our relations with the global ‘order of Being’.18

William Rees thinks conscience needs some help, and calls for a new kind of myth-making, the creation of unifying stories to foster those aspects of human nature that are biologically and ecologically tuned in. It would be, he says, ‘a purposeful act of social engineering’.19 Another kind of modelling, in other words. Stories don’t work like that, though. Good stories – and none more so than those written in the barefoot prose of Tolstoy – are more like ecologies than technologies. They work through living networks of interdependency, and pulse with energies too nervous to resolve themselves into any parcel of messages. Instead, they generate images and associations that cross-flash with uncanny complicity between the hemispheres of the globe, from one era to another as if, through them, we were trying to tell ourselves something.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Helena Grehan, Sylvia Lawson and Stephanie Dowrick for their generous engagement with earlier drafts of this essay.

Endnotes

1 http://www.footprintnetwork.org/calculator

2 Leo Tolstoy, ‘How Much Land Does a Man Need?’ in The Raid and Other Stories, Oxford University Press, 1982, pp 213–14.

3 Paul Carter, The Lie of the Land (London: Faber and Faber, 1996), p. 2.

4 John Gascoigne, Captain Cook: Voyager Between Worlds, Hambledon Continuum, 2007, p. xiv.

5 Aeneas Gunn, We of the Never Never, Random House, 2000, pp 38, 107.

6 http://www.mataranka.nt.gov.au/council/

7 Nevil Shute, A Town Like Alice, Gecko Books, 2006, p. 411.

8 Kate Grenville, The Secret River, Text, 2005, p. 3.

9 Henry David Thoreau, Walden and Civil Disobedience, Penguin, 1986, p. 53.

10 Paul Hawken, Blessed Unrest, Viking, 2007.

11 William Rees and Mathis Wackernagel, Our Ecological Footprint: Reducing Human Impact on the Earth (1996)

12 W.E Rees, 2004, ‘Is Humanity Fatally Successful?’ Journal of Business Administration and Policy Analysis, pp 30–31: 67–100 (2002–03), 90.

13 John Krakauer, Into the Wild, Random House, 2007.

14 Into The Wild, dir. Sean Penn, Paramount Pictures, 2007.

15 Václav Havel, Statement delivered at Forum 2000, Prague Castle, 4 September 1997, 3, 5. Online at http://www.cts.cuni.cz/conf98/vhavel.htm

16 Walter H.Capp, ‘Interpreting Vaclav Havel’, Cross Currents, Fall 1997, Vol.47 Issue 3, 6. On line at http://www.crosscurrents.org/capps.htm

17 Václav Havel, ‘The Politics of Hope’ in Disturbing the Peace: A Conversation with Karel Hvizdala, trans. Paul Wilson, Vintage Books, 1990, p. 189.

18 Václav Havel, Address to A Joint Session of the U.S.Congress, Washington DC, 21 February 1990. Full text available online at http://www.vaclavhavel.cz/showtrans.php?cat=projevy&val=322_aj_projevy.html&typ=HTML

19 Havel, ‘The Politics of Hope’, pp 96.