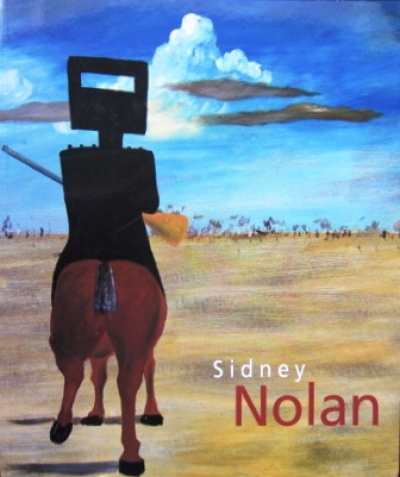

Sidney Nolan

This is a beautiful, thought-provoking, and timely exhibition about the enduring power and relevance of myth to humanity. In fact, visitors get two exhibitions in one, in the way that TarraWarra Museum of Art does exceptionally well: with contemporary art speaking back to Australian modernism – the original core of the museum’s permanent collection.

... (read more)Out of Australia: Prints and Drawings from Sidney Nolan to Rover Thomas by Stephen Coppel

Nolan on Nolan: Sidney Nolan in his own words edited by Nancy Underhill

Art is a strange posing of discoveries, a display of what was no more possible. For it is the task of the creative artist to come up with ideas which are ours, but which we haven’t thought yet. In some cases, it is also the artist’s role to slice Australia open and show it bizarrely different, quite new in its antiquity.

Half a century ago, Sidney Nolan did just this with his desert paintings and those of drought animal carcasses. I recall seeing some of these at the Peter Bray Gallery in 1953 and being bewildered by their aridity: a cruel dryness which made the familiar Ned Kelly paintings seem quite pastoral. Nor could I get a grip on his Durack Range, which the NGV had bought three years earlier. Its lack of human signs affronted my responses.

The furthest our littoral imaginations had gone toward what used to be called the Dead Heart was then to be found in Russell Drysdale’s inland New South Wales, Hans Heysen’s Flinders Ranges, and Albert Namatjira’s delicately picturesque MacDonnells. Nolan’s own vision was vastly different: different and vast. It offered new meanings and posed big new questions.

... (read more)