Obituary for Helen Daniel

Helen Daniel, the editor of Australian Book Review since 1995, died suddenly on Monday, 16 October 2000. Her death has sent waves of shock and sorrow throughout the Australian literary world. According to Andrew Riemer, at the Writers’ Week in Brisbane, held on the weekend after Helen’s death, session after session paid homage to this woman who, without vanity or arrogation, had made her name synonymous with the profession and apprehension of Australian literature.

Her death diminishes all of us. It’s strange to reflect that Helen, who occupied her position so quietly (at times so stoically) was in fact far and away the greatest champion for Australian writing in her generation and that her time as a critic and editor coincided with the great efflorescence of Australian publishing that we now wonder at and ponder.

Helen Daniel was an enthusiast. She didn’t simply want to push the Australian writing she happened to think good, it was as though Australian writing was the very ground of her being. And this passion was always inclusive and accepting in a way that put a lot of us to shame. Quite a few years ago now, I recall Helen setting about editing her Good Reading Guide to Australian fiction, to which she invited me to contribute. At that time I was editing Scripsi with its international emphasis, and I was completely unable to understand how a guide book could work if, as Helen decided, it was to exclude negative criticism. Helen believed the book could function implicitly, but with some high-handedness I not only refused to contribute to it but added insult to injury by reviewing it scathingly and sarcastically when it appeared.

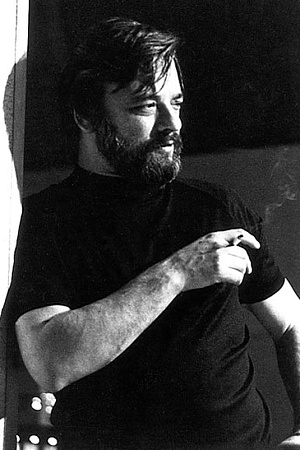

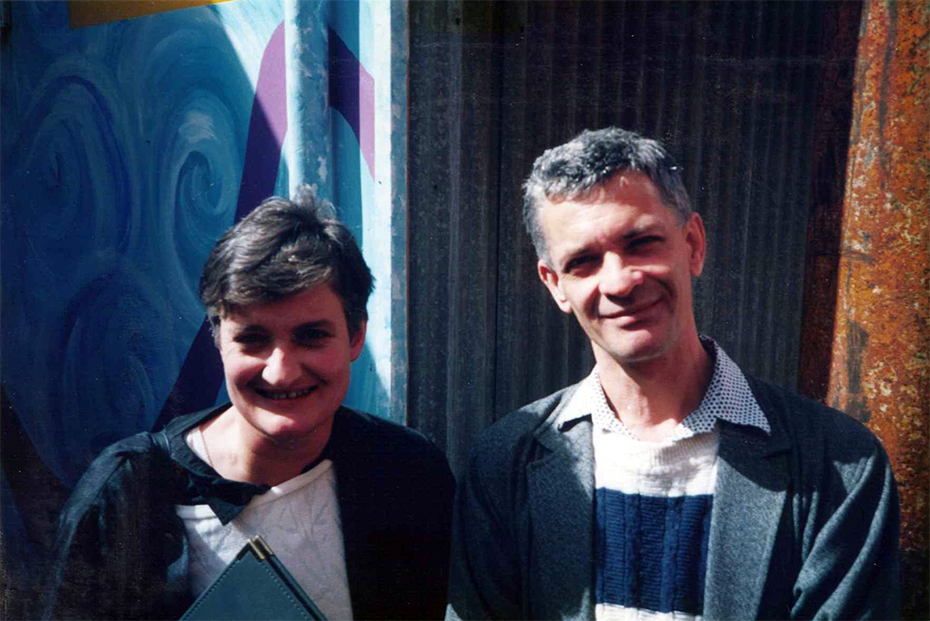

Helen Daniel (Editor of ABR 1995–2000) with Robert Dessaix, a contributor since 1981 (photograph by Peter Rose)

Helen Daniel (Editor of ABR 1995–2000) with Robert Dessaix, a contributor since 1981 (photograph by Peter Rose)

I will never forget the sequel to this, because it was so characteristic of Helen. A week or two later we both found ourselves at some gathering of the literary tribes at a boathouse by the Yarra River. Helen came up to me and she said in that forthright, mild-mannered way of hers, ‘Peter, I just wanted to say that I disagreed completely with everything you had to say about my book, but I want you to know that I don’t have any hard feelings about it and I don’t want it to stand in the way of our working together.’ It was a humblingly decent thing to say and it also showed Helen’s characteristic courage because of the in-built risk of being snubbed.

It is courage that runs like a leitmotif through the life of the Helen Daniel we knew as a professional colleague and friend. She never backed away from controversy, but you never felt with Helen that she went into it because of a streetfighter’s predilection. She would call for the resignation of the Miles Franklin judges or pursue to the end the logical consequences of the Demidenko/Darville debate, but she never gave the impression of making love to that employment. She also gave the impression of taking the public positions she did simply (and with great purity of heart) because she thought that it was the right thing to do. She also had, to a greater degree than anyone I have ever known, a respect for people who looked at the same questions and thought otherwise. True democrats are the rarest thing on earth among the clamorous oligarchies and crumbling kingdoms of our own opinionated dispensation, but Helen was one of them. She believed that she sometimes had a duty to speak out, but she didn’t believe that she had any more right to be heard than any of her peers.

None of which is meant to make her sound like a goody-goody two shoes of critical sanctity. For a long time there she enjoyed the cut and thrust, the bustle and extroversion of the literary life. I remember her telling me of a particular encounter she had had in a famous academic environment. It was the Year of the Demidenko Hoax and Dr Daniel was on the campaign trail. She found herself sitting, as a guest, at a public seminar in the Melbourne University English Department. Before she spoke, the then-chairman, a very senior academic and a sedulous proponent of poststructuralist theory, said, somewhat pre-emptively, The Hand that Signed the Paper is a book made up of marks on paper. It is a text and it has no more relation to any supposed real world out there than any other text does. The Holocaust is just a signifier that operates within that text and between it and other texts.’ When Helen told the story, her voice took on those little girl tones that were an intimation of whimsy or impishness. ‘He just provoked me to insolence and I couldn’t stop myself, “Where am I?” I said. “I must be dreaming. What is this place?”’ And then, having evoked the bewilderment of an Alice in Wonderland world she added, ‘I know. I must be in the Melbourne University English Department.’ As if looking-glass worlds and Humpty Dumptys who used words to mean any old thing were par for the course. At that moment, she showed a greater worldliness than her interlocutor, but she would have believed passionately in his right to his wrongheadedness.

Helen Daniel had her own sustained dealings with literary criticism. Liars is an attempt to come to terms with the new fabulism, and it is mediated through her awareness of the Godel, Escher, Bach thesis. Her account of Peter Carey and Murray Bail, David Ireland and Peter Mathers and Gerald Murnane, David Foster and the rest of them is a real attempt to come to terms with home-grown efforts at what might be a modernism or postmodernism and, in complex ways, it is easier for readers to make their way among those floating glass churches, those endless plains and portable museums of the imagination, because Helen gave them her concerted attention.

She also persuaded Penguin to publish her monograph about David Ireland, and it is part of her legacy that it will be harder for us to forget the dinosaurs and tortoises of our literary landscape, the solitary creators who in a turning world may not bring out a book for years, because Helen Daniel never forgot them. Indeed, if you look back at the reading guide that I gave such short shrift to, you will see evidence (and where else would you readily find it?) of the start of a canonical consensus about the Mathers and Murnanes.

She was also an energetic and imaginative editor of anthologies, sending great swags of writers off down the Cahill Expressway or in pursuit of the millennium or just sifting through the splendours and miseries of new writing with the likes of Robert Dessaix and Drusilla Modjeska. All of which seems with hindsight to have been leading up to Helen Daniel’s assumption of the editorship of Australian Book Review, which she took to as if she had come into her kingdom. All of Helen’s patience and tenacity, all of her ability to stick to a deadline or hold to a given stance while tolerating divergence shone and shone through her work. The famous Voltairean tolerance, that impassioned defence of human variousness, worked in practice when she was dealing with her contributors to displace attention back on the quality of their writing, not the rightness of their opinions.

And the editorial upshot could be quite remarkable. One of the tests of a literary magazine editor working under every kind of temporal and financial constraint is whether he or she can nevertheless, every so often, and against the odds, provide the most definitive treatment a book or an idea will receive. Under Helen Daniel, ABR did this time after time. Helen ensured that this monthly journal of record was not an adjunct to the broadsheet literary pages or a kind of marsupial version of The Australian’s Review of Books (much as she would have liked to go fortnightly, much as she could envisage an international component). She made it the natural meeting place of the imaginative and intellectual world we inhabit. Her ABR was where we fought and wrangled. It was where we had the space to say, on occasion, what we really felt.

Examples of the excellence of Helen’s ABR abound but I will give two of them that happen to strike me. In the heat of the debate about The Hand that Signed the Paper, it was a piece Helen published by Robert Manne that in the midst of my semi-ignorant bemusement suddenly made me realise what the fuss was about. And it was the essay Helen commissioned from Inga Clendinnen that made me realise that the distinguished historian of the Aztecs was also a powerhouse of language and sensibility.

In my own dealings with her, as a contributor to ABR under her editorship, Helen was a dream of an editor to work with. Who else would have allowed me to review Germaine Greer or Inga Clendinnen’s book about the Holocaust? Who in their right mind (or let’s say with their cautious, conventional hat on) would have dreamt of courting impropriety by asking me to review Mark Davis’s Gangland?

The glory of Helen Daniel’s Australian Book Review was first its excellence and secondly the fact that it was communitarian. One of the things it’s easy to forget when you’re part of the literary world and have an automatic ‘sophisticated’ awareness that the best of our literary product is pretty good is that the nearest young person (starved, it may be, by her teachers) may have no such awareness. The other, less obvious, side of the equation is that the knowledge most of us have, even when we are professional literary critics, would be nothing compared to the range and intensity of Helen’s reading of Australian writing.

Nor, in many cases, is it meant to be. But that is not the point. She invited all her sharpshooters and snipers into the library, into the pages of her journal and there has been ever since the gaudy, sometimes blood-bathed spectacle of those symposia which Helen would set among us like so many distorting mirrors or temptations to folly. They were good for us, I think. As Helen herself was, so selflessly, so generously, with such stoicism, when a few years ago, after her partner Margaret died, the dark night of the soul came upon her and seemed to last an age.

I know of no activity on earth more exasperating and, perforce, more extroverted than editing. You sit by the phone, chatting and wheedling in order to impose your will upon the contributor and for the relief of behaving like a human being during a hectic business. I cannot begin to imagine what is was like for Helen to continue to edit, as she did, after she had ‘lost her words’, when she was bereft of small talk, when she was, in respect to everything but her editorship of the magazine, bereft.

She seems to have held on to it like a lifesaver and we are in this dead woman’s debt that she could be so brave, that in the midst of desolation she could still retain the face of altruism. It was Yeats, I think, who asked: why do we honour those who die in battle when a person may show as reckless a courage in entering the abyss of themselves? When Helen died, I thought of those lines of Hopkins: ‘O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall / Frightful, sheer, no-manfathomed / Hold them cheap / May who ne’er hung there.’

It is a deep consolation to those of us who knew Helen Daniel and cared for her that in the last year or so of her life she seemed to come out into the light. The mask of melancholy seemed to dissolve. She would laugh and joke, there was the white wine, and there were the cartloads of Marlboro. She seemed to be herself again.

Her death now, unexpectedly, falls like a calamity on a literary world that cherished her in ways she scarcely knew and will forever be her debtor. She was one of the makers as she was one of the custodians of Australian writing. May she rest. May the wind blow with her.

This is an edited version of the speech that he gave at Helen Daniel’s memorial service at Newman College Chapel.