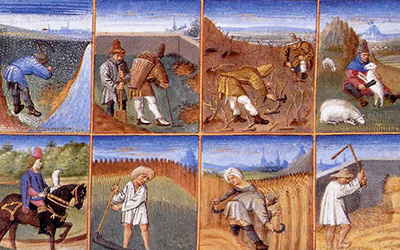

‘When we talk about the Middle Ages: Revisiting the power of periodisation’ by G. Geltner

Few terms capture the imagined structure of European history as succinctly, and aptly, as ‘the Middle Ages’. Whether the era is being invoked fondly, casually, or with deep disdain, the term at once offers a comprehensive, normative account of civilisation and casts aspersions on those out of sync with it. It was designed to do just that. ‘The Middle Ages’ inserts itself as an antithesis between two seemingly cohesive periods: Antiquity and the Renaissance (the latter soon to be replaced by Enlightenment and then Modernity). It thus creates continuity by underscoring rupture, and stresses similarity through difference. Despite the era’s appeal to the Romantics and nascent nationalism in the late eighteenth and the nineteenth centuries, respectively, its poor reputation has been steady: from Jules Michelet’s quip about ‘the Middle Ages’ being ‘one thousand years without a bath’, to Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction, where Marsellus Wallace famously vows ‘to get medieval’ on his torturer’s ass.