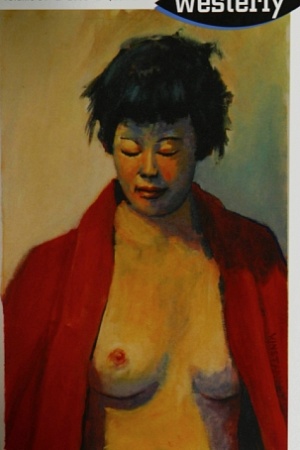

Not Being Miriam

Fremantle Arts Centre Press, 192 pp, $14.99 pb

Not Being Miriam by Marion Campbell

Three sections at the beginning of Marion Campbell’s second novel, Not Being Miriam, initiate its preoccupations and problems. They relate incidents from the childhood of Bess Valentine, its major character. In the first and shortest, Bess creates a transforming ritual, a childish game with significant narrative implications. Bess strips herself and Sean, paints their bodies with clay, the children enter the water which washes away the clay; then she dresses in Sean’s boxer shorts and clothes him in her bubble bathers. Now, she tells him, he’s the bride and she’s the groom; and the section ends with an incantation:

This is the wedding

This is the wedding

I take you for my wife

I take you for my husband

This is the ring

This is the ring

This is the kiss

This is the kiss

This is the cave we’ll live in

This is the cave

indicating the innocent surety of this stage of Bess’s life. She controls the pattern that anticipates her future.

Older, in the second section, Bess can no longer create her world, but seeks to know it. She’s sceptical of the Sunday school ritual that acknowledges Peter as the rock of the church, and of the games played by her younger sister Cassandra and Peter Petra. Searching out their secret, she finds a cubby Peter has built and can’t resist going into it despite its misspelt warning notice: ‘PETER’S LABRINTH ENTER AT YOUR RISK’. Unlike the purity of the first game and Bess’ autonomy in it, this one has been established without her and is overlaid by social prohibition. As Bess shoots out of the seductive, dangerous darkness of the labyrinth, she’s propelled both by Peter’s mother’s indignant disgust as this ‘thing’ of Peter’s, as well as by her need to understand the word, ‘lab[y]rinth’, thus the meaning of the other’s game. Her myth book is her source for the knowledge she seeks; now, she thinks, she can be Ariadne ‘who learnt the plan, drugged the guards and gave the thread. Who knew.’

Peter and Cass are unwilling participants in Bess’s game in the third section. Bess and Cass, behind the hessian Bess has stretched over the workbench in the backyard, are radio presenters. Peter is the listener, with the power to choose his station. Around them is the world Bess has made – ‘all theatres, inside, outside, up trees, underground, behind the shed, down near the jetty.’ Abandoned by Cass and Peter, Bess becomes the game, she enters the News, and it’s violent and retributive. Game and reality merge, a snake is killed, and Cassandra labels Bess ‘Murderer’.

The language – from the exquisite simplicity of the first to the density of the third and increasing length of these introductory sections reproduces the growing complexity and restrictions of the maturing child’s life. As the narrative moves into Bess’s adult life as a high school drama teacher, caught in the conventions of discipline and examination, in the constrictions of life as a single, middle-aged woman in an Australian suburb, and in the irony of her past promise and reduced present, loss and compromise seem inescapable. So does the impossibility of retaining the early charm and freedom of being a scallywag, as Bess’s mother labels her at the beginning, of controlling her own destiny by presenting life as a performance, But Bess keeps trying to plan its drama.

As readers, we must learn the narrative plan by following its threads through the labyrinthine stories. Threaded through the conjunctions of Bess’s childhood and adulthood are the lives of other women (and men). Chief of these are Lydia, the German-born wife of Bess’s colleague and one-time lover, Harry Grogan, and illiterate Elsie, victim of incest and domestic abuse and Bess’s neighbour. Each of them has another woman as a point of reference, as Bess has Ariadne. For Elsie it’s the second Mrs de Winter, the mousy, nameless heroine of Rebecca; for Lydia, it’s Katerina Kepler, the doomed witch mother of Johannes Kepler. These counterparts provide an imaginative expansion and sharing (Bess, for instance, is called a witch) of the women’s lives through the roles they suggest. They allow, too, for both reinforcement and comedy – playing charades at Christmas to the well-meaning but patronising audience of Lydia and Billie, Elsie ‘done my Mrs de Winter ... (first Mrs sounds like kisses and then I puffed and blew and shivered for winter)’ – as well as intimating failure and tragedy.

There are more. Cassandra waits in the wings to take over Bess’s part, to move into her everyday life, having achieved the success Bess had been promised; there’s the sisters’ aunt, Mamie, who taught them her sophisticated role playing, gender bending games; there’s Billie, Lydia’s friend who has the beach house where she and Lydia play Scrabble with Harry as an impotent audience. And Miriam is the ultimate Other, the absent type of them all, that indefensible, sacred other woman of male fantasy who is eternally young, flawless and beautiful because she’s dead.

Behind them are the male figures, presences that seduce, threaten, promise and brutalise. Some of them are kind, but although they have few of the answers or talents they hold all of the overt power. Triangular relationships structure the stories; presaged in the Bess, Peter, Cass figure at the start, and repeated conventionally through Bess, Harry and Lydia and less so through Elsie, Roger and Bess. In them, however, the women are less rivals than allies, drawn together emotionally and finally physically in the bizarre climax of Bess’s story.

While the women’s lives are marked by loss and failure, repeating in their ‘crazy sacrifices’ that ‘founding loss’ that was Ariadne’s, they have their own power and their triumphantly subversive mechanisms. Wonderfully memorable comic moments celebrate that female rebellion against the masculine authority which, like the promises of the ambiguous gods of mythology, attempts to keep women in their place. Caught and treated with contempt by her boss as she feeds her baby in the Kalgoorlie cafe where she’s been the drudge, Elsie imagines ‘squirt[ing] them all, using her breast like a fire hydrant.’ The comedy, and pathos, explode as Elsie leaves, blinded by tears and abandoned by her own special magic that enables her to ignore the taunts of those around her, and slams the pram with the squalling baby into a wedding party in the wide, hot main street.

This is a demanding novel to read, and a daunting one to review; any attempt to describe it risks reducing its wit and audacity, its narrative power and complexity. Sometimes, the narrative games take over and meanings expand until they become unintelligible. Often, the referential detail and language play is sheer, punning delight. In the section called ‘From Ariadne’s Yarn’, Ariadne’s story, her career through history where she’s always off stage – her only ‘entry’ in the dictionary is under ‘A for Abandonment’ – is developed in a dazzling series of often savage puns, female weapons against males who despise language games because they ‘upset their curricula vitae’. Here, Theseus’s monster is Ariadne’s ‘minotaur’; she’s ‘not going to be mythtaken’ and will ‘underpun’ their purpose.

Allusions, classical and literary, especially theatrical, criss-cross the narrative, and it generates its own referential motifs, like Mamie’s wishing well lamp, a haunting reminder of the possibilities and hollowness of female desire, or the unattainable male-generated Miriam of the title, against whom the ordinary women of the story are, ambiguously, perhaps positively, perhaps negatively, ‘not being’. Not Being Miriam is important, too, in its social as well as its narrative concerns. While the impulse of the narrative is a feminist one, there is no sentimental recreation of an ideal sisterhood; no heroic realisation of Bess’s talents and beauty; no pathetic rendering of Elsie’s disadvantages. The women’s stories are presented honestly and their differences are part of the meanings as the female lives, contemporary, historical and mythological, touch and overlap.

As the weaving metaphors of the last section, ‘Ariadne’s Option’, fan out beyond the end of the novel and reach back to the beginning, the composite woman Ariadne/Bess/narrator becomes the sea, the beach, the mother. The blindness assigned by the gods to the feminine gaze is made knowing, ‘new, tactile, intimate’. Finally, ‘She is ready’; a readiness (for her entrance, to play her role, to become the darkness?) reinforced by the image immediately preceding ‘Ariadne’s Option’ of Mamie and Elsie, armed linked, swaying on the beach at night, throwing a shadow case by the lighthouse beam that ‘four-legged ... danced for miles along the beach.’ This narrative is just such a dance, celebrating and justifying the women’s stories it tells.