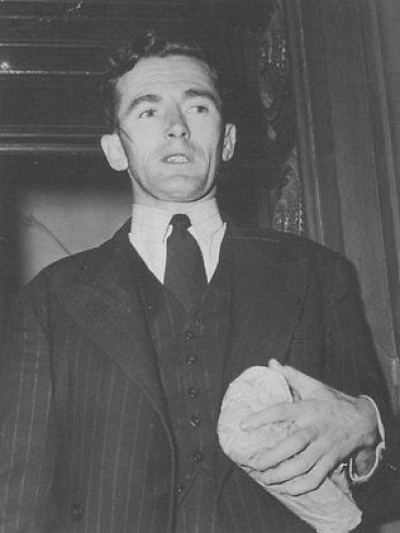

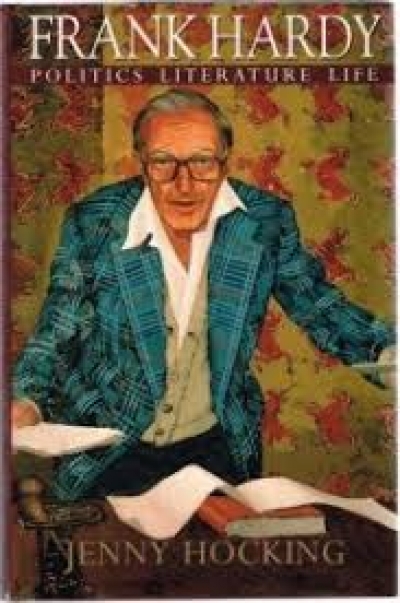

Frank Hardy

The portrait likely to emerge in this article will be more that of a trend in Australian literature than of a writer named Frank Hardy.

... (read more)La Trobe University Essay | 'A BIG LIE: Manning Clark, Frank Hardy and "Fictitious History"' by James Griffin

‘People are not entitled in a civil society to pursue a malicious campaign of character assassination based on a big lie.’ This was Andrew Clark, son of the historian Manning Clark, expressing understandable outrage on behalf of his family. The issue was the infamous allegation, based on nebulous evidence, that Manning was ‘an agent of Soviet influence’ and had been awarded the Order of Lenin. Unfortunately, as the Clarks will know, the big lie, even when refuted, spreads across generations. Although the onus is supposed to be on the accusers to prove their allegations, in reality it is easily, plausibly reversed.

... (read more)The Frank Hardy I Knew

Dear Editor,

Frank Hardy was a larrikin. It was probably one of his most endearing qualities, but he did tell me once that his membership of the Australian Communist Party enabled him to become something more than a larrikin. He didn’t always pay his debts, except for the one big debt and the only one worth remembering: the debt of living, to the end, a writer’s life. For a boy brought up amongst working-class Irish Catholics in the potato belt in Victoria, that was no mean feat.

... (read more)