Land of Mine ★★★★

Martin Zandvliet’s Land of Mine is unsettling from the very outset. During the credits a recurring sound becomes audible, then consuming: the sound of heavy, ragged breathing. Sergeant Carl Rasmussen, sitting in Danish army fatigues and a maroon beret, he is watching a column of grim-faced German prisoners of war. Inscrutable, he drives past soldiers, then stops and throws his jeep into reverse. He jumps from the vehicle to assault a German who is carrying a Danish flag. ‘This is not your flag. This is not your home!’ Punching the German in the face, Rasmussen screams, ‘This is my land!’

The film’s original title, Unter Sandet, was a metaphor rather than a pun. Just as the Germans mapped what lay ‘under the sand’ of the nation’s beaches, the film maps the periphery of the nation’s history, part of which it shares with Germany. Anticipating a northern Allied invasion, German soldiers planted more than 1.4 million landmines along the Denmark’s western coast. After the German surrender, some 2,600 prisoners of war were reclassified as ‘voluntarily surrendered enemy personnel’ in order to bypass the Geneva Convention, and conscripted to clear the mines. Many – the precise number remains unclear – were from the Volkssturm, a militia created in the final stages of the war from the remaining male population, too young or too old to have fought in the war earlier. Zandvliet’s film, focused on a unit of fourteen adolescent Germans, is an elegant, understated attempt to balance narratives of good and evil in World War II.

Coincidentally, before the preview a trailer screened for Denial, based on the libel case brought by the historian David Irving against Penguin Books in 1996. Irving became a Holocaust denier after reading a specious report authored by Fred Leuchter, an arts graduate who worked as an execution engineer. The report was commissioned by Ernst Zündel, in his defence in a Canadian court against the charge of reporting false news. Although much of Leuchter’s supposedly expert evidence on gas chamber engineering and toxicology was dismissed, and though Zündel was found guilty, the Supreme Court later overturned the conviction – not because his pamphlets were correct, but because the Canadian Constitution protected the spread of all news, true or false.

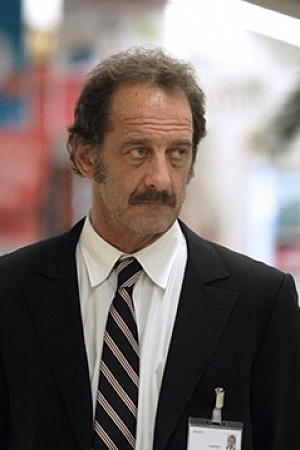

Roland Møller as Rasmussen in Land of Mine (Palace Films)

Roland Møller as Rasmussen in Land of Mine (Palace Films)

Land of Mine is not, of course, ‘false news’. It is one of those projects which aim to correct the historical record of World War II without straying, like Holocaust denial, into falsehood. The carpet bombing of German cities, for instance, which Irving has also written about, is now well understood. Max Sebald’s On the Natural History of Destruction (2003) undoes the idea, ingenuous or disingenuous, that the Allied nations were wholly ‘good’ and the Axis wholly ‘evil’. One cannot think of the boiling of human flesh in man-made firestorms – strategic infernos – and hold to such binaries.

The film does not deny the reality of German wrongdoing, but it remains quiet on the subject. Zandvliet signals, from Rasmussen’s opening outburst on, the colossal evil of the Third Reich. While such signage is effective, however, it is not always affective. The violence done to Denmark from 1940 to 1945 is represented only by Danish rage and spite; all the violence on screen is Danish. The film’s point of view is that of the boys; their wretchedness is tautly recreated as they train with live mines and perform their dreadful work. Zandvliet’s camera lingers on the boys’ faces. He cites the influence of the American documentary filmmakers David and Albert Maysles, whose filming was ‘so vulnerable and sensuous that you could not help feeling the presence of their characters’. The boys are profoundly vulnerable; they bear the brunt of Denmark’s anger at the crimes of their brothers and fathers, and their country’s menacing weltanschauung. This ‘group of boys’, writes Zandvliet, were ‘forced to do penance on the behalf of an entire nation’.

Louis Hofmann as Sebastian in Land of Mine (Palace Films)

Louis Hofmann as Sebastian in Land of Mine (Palace Films)

The film addresses this injustice without flinching. An older woman sitting near me left halfway through the film, muttering ‘that’s enough for me’. It is a frightful thing to watch a teenage boy explode, but here it is not gratuitous. Despite the sympathy the film elicits, the statistics which appear in white against black at the finish wrench us from its close world and from the faces of the boys, into the present one of history and its deniers. How can we mourn some 1,300 German lives – even boys, drafted by the Nazis – set against the millions of victims of Nazi atrocities? Land of Mine quietly asks, to the contrary, how can we not?

Land of Mine, 101 minutes, directed by Martin Zandvliet. Distributed in Australia by Palace Films. In cinemas from 30 March 2017.

ABR Arts is generously supported by The Ian Potter Foundation.

Comment (1)

Leave a comment

If you are an ABR subscriber, you will need to sign in to post a comment.

If you have forgotten your sign in details, or if you receive an error message when trying to submit your comment, please email your comment (and the name of the article to which it relates) to ABR Comments. We will review your comment and, subject to approval, we will post it under your name.

Please note that all comments must be approved by ABR and comply with our Terms & Conditions.