A tribute to Stephen Sondheim

‘See George remember how George used to be,

Stretching his vision in every direction.’

I’ve often wondered what it would be like to witness the extinguishing of a genius who not only defined an era or a movement but also ruptured an art form. Virtually nothing of Shakespeare’s death is recorded, so we are left to invent the dying of that light. Mozart’s funeral was infamously desultory, and Tolstoy’s swamped by paparazzi as much as by the peasantry. Stephen Sondheim, the single greatest composer and lyricist the musical theatre has ever known, died at his home in Connecticut on 26 November, and we who loved him feel the loss like a thunderbolt from the gods. Not because we’re shocked – he was ninety-one after all – but simply because we shall not see his like again.

Sondheim’s biographical details are familiar, from the depressing years with his avaricious, social-climbing mother to his seminal private one-on-one tutorials with family friend Oscar Hammerstein II. His stratospheric rise to fame as the twenty-seven-year-old lyricist of West Side Story (1957) and a string of massive hits with producer Hal Prince in the 1970s were tempered by his infamous flops: Anyone Can Whistle (1964) originally played for nine performances, and Merrily We Roll Along (1981) for sixteen. Surprisingly little is known of his private life: even the fact of his coming out as gay is disputed, some sources saying he did so when he was forty, others that he didn’t publicly come out until he was almost seventy. He was certainly a workaholic; almost everything we know about him is tied to his artistic output.

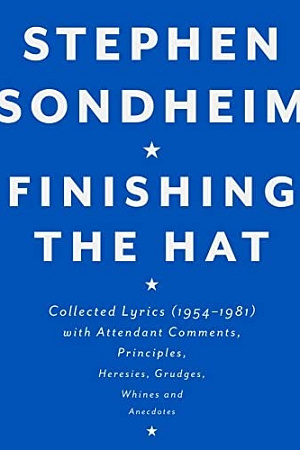

And what an output! Those first few musicals – when he was exclusively a lyricist to such master composers as Leonard Bernstein, Jule Styne, and Richard Rodgers – demonstrated his talent for wordplay and witticism, as well as his particular sensibility for idiom and vernacular. He chided himself for that early work on West Side Story, arguing in the first volume of his indispensable collected lyrics, Finishing the Hat (2010), that lines such as ‘Today the world was just an address’ and ‘Tonight there will be no morning star’ wouldn’t have come out of a kid from the streets of New York. ‘Tony is a dreamy character, but it’s unlikely he’s even seen a morning star (you don’t see stars in Manhattan except in the Planetarium).’

Sondheim was never going to remain merely a lyricist. Having already written a number of full scores before he reluctantly accepted the West Side Story gig, he always claimed to enjoy musical composition far more than lyric writing. When he finally escaped the shackles of other people’s talent, his penchant for formal experimentation and unusual subject matter became instantly recognisable. Anyone Can Whistle might have flopped spectacularly, but it hung some of his most iconic songs on a truly batty plot that featured fake miracles, escaped lunatics, and outrageous political corruption. Company (1970), with its plotless structure and disparate dramatic vignettes tied by a central theme, changed musical theatre for good. A show like A Chorus Line (1975) is inconceivable without it.

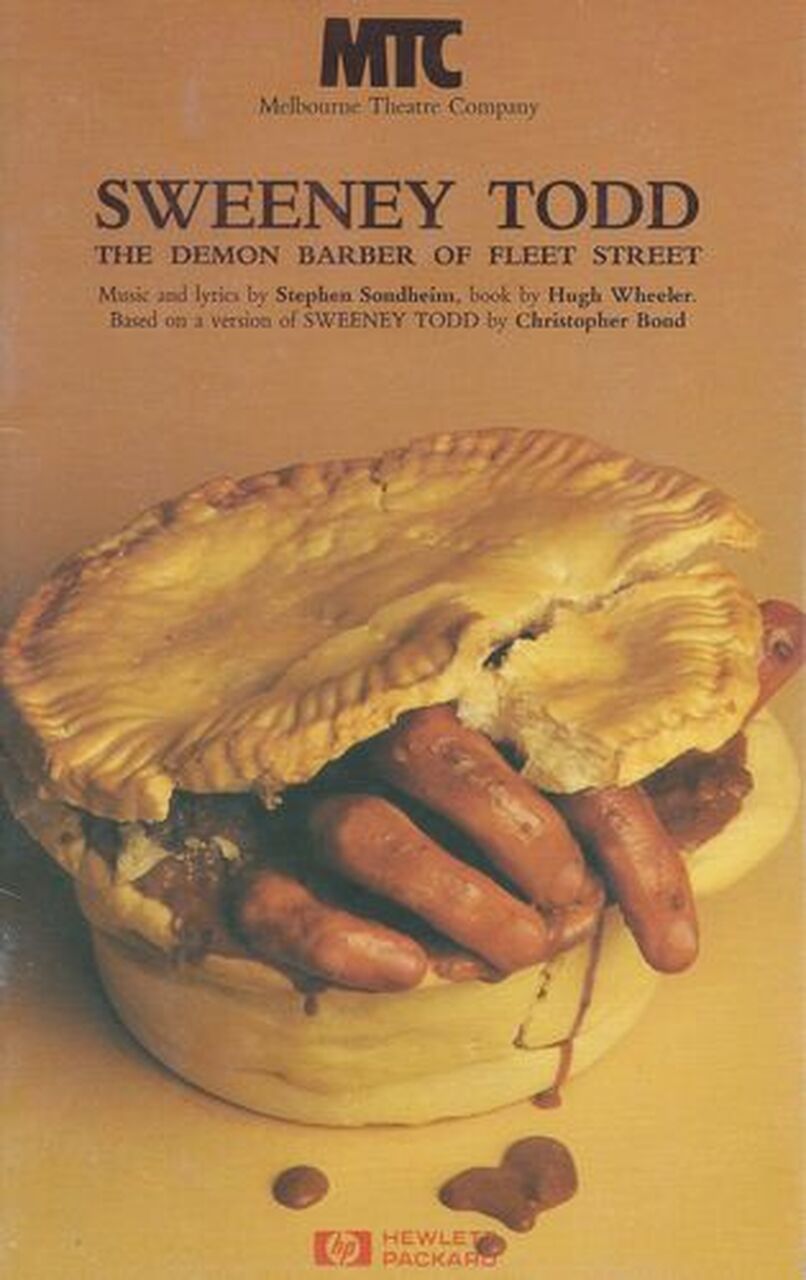

Melbourne Theatre Company's 1987 Sweeney Todd playbill.

Melbourne Theatre Company's 1987 Sweeney Todd playbill.

My formative experience of Sondheim came when I was thirteen years old, the first time my best friend and I were allowed to go to the theatre by ourselves (our mothers dropped us off and picked us up afterwards). It was Melbourne Theatre Company’s 1987 production of Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street (1979), starring Peter Carroll and Geraldine Turner, and directed by Roger Hodgman. When the deranged Sweeney turned to the audience, the glint of murder in his eye, and asked ‘Who’s for a shave?’, it felt as though he were talking directly to me (it never occurred to me that I was too young for a shave). From that instant, I was hooked. My friend and I went home that night and began a lifelong love affair with the composer’s work, scouring record stores for Broadway cast albums, poring over his lyrics, devouring every article written about his artistry. That’s the wonderful thing about discovering a mid-career artist: you have an extraordinary back catalogue to work through, and the anticipation of future works.

Some of his shows became instant favourites – Into the Woods (1986) dealt so sharply with the tumescent peril of sexual awakening I remember coming home from my first make-out session to listen to ‘Moments in the Woods’ as a way of debriefing – and others grew slowly on me. I remember the shock of listening to the original cast recording of Passion (1994), the discovery of a Sondheim score virtually denuded of his trademark urbanity and wit. It wasn’t until I watched the video of the Broadway production at the house of the late great Australian film director and Sondheim friend Richard Franklin, and we all sat around crying over the work’s high Romanticism and emotional fragility, that I finally understood it. Franklin loved the piece, but his wife at the time found it too exposing, as if Sondheim had revealed too much of himself to the world.

It is impossible to settle on an absolute favourite; my loyalties keep shifting, and I find certain scores speaking to me at certain times in my life, or even at different times of the day. Nothing can be discarded or entirely overlooked, from ‘Can That Boy Foxtrot!’, written for and cut from Follies (1971), to the divine ‘I Remember’, from his made-for-television curio Evening Primrose (1966). Sondheim is the only composer I can think of whose cutting-room floor songs have been refashioned into a musical of their own, the utterly delightful if only barely coherent Marry Me a Little (1980). Lesser-known shows such as Pacific Overtures (1976), about the opening up of Japan in the ninteenth century, and the troubled but satisfying Road Show (2008) might be minor works in his oeuvre, but they contain masterful examples of his songwriting skill.

Performers adore Sondheim for the same reason they adore Shakespeare: he gives them so much to do, but also passes through them like they’re doing nothing at all. The placement of the emphasis, the use of crescendo and decrescendo, of metre and rhyme, the simplicity of the dramatic line merging with the complexity of the emotional register; it’s all there on the page. He’s incredibly difficult to get right, but when you do it looks effortless. Some of the greatest stars of the stage owe everything to Sondheim and wouldn’t deny it. Bernadette Peters, Patti LuPone, Mandy Patinkin, Angela Lansbury, Elaine Stritch, Imelda Staunton: they didn’t just cut their teeth on Sondheim, they were made immortal by him.

Lee Remick, Angela Lansbury, Harry Guardino, and Herbert Greene backstage at Broadway production of Anyone Can Whistle. (Wikimedia Commons)

Lee Remick, Angela Lansbury, Harry Guardino, and Herbert Greene backstage at Broadway production of Anyone Can Whistle. (Wikimedia Commons)

Awards were, sensibly, one of Sondheim’s great ambivalences: while he won an Oscar, a Pulitzer, and several Tony awards, he never lost his healthy distrust of them. In volume two of his collected lyrics, Look, I Made a Hat (2011), he said that awards ‘have three things to offer: cash, confidence and bric-a-brac’. He expressed a particular distaste for Lifetime Achievement awards, which for him denoted ‘the slippage from respect into veneration’. If he cared little for them, his fans cared on his behalf. I still haven’t forgiven Jerry Herman for his sly dig at Sondheim as he accepted the Tony for Best Musical in 1984 for La Cage Aux Folles, over the far superior Sunday in the Park with George. Herman talked of ‘a rumour … that the simple, hummable show tune was no longer welcome on Broadway. Well, it’s alive and well at the Palace.’ I know whose score I listen to over and over, and it isn’t the one with the garish queans.

As for legacy, it’s something we will discuss for as long as his theatre exists. The key thing is his ability to hold contrasting ideas in suspension, that delicate oscillation between the extremes of cold rationality and lush Romanticism that seemed to define his persona. Sondheim was a man of the city, his town civility and sophistication intrinsically linked to his talent, and the vast bulk of his characters were the same. When they do venture out into the country, they take their urbanity with them. Fredrik sings in A Little Night Music, (1973) ‘I should never have gone to the theatre. Then I’d never have come to the country. If I never had come to the country matters might have stayed as they were.’ But this cultivated nature was, again like Shakespeare, as comfortable with his working-class characters, such as the maid Petra from the same show, who sings of the ‘very short way from the fling that’s for fun to the thigh pressing under the table’.

Sondheim did longing and disappointment better than anyone. In ‘Like It Was’, from Merrily We Roll Along, Mary sings so directly, plaintive and cutting at once, of the past and its poisonous effect on the present. ‘Charley, why can’t it be like it was? I liked it the way that it was, Charley, you and me, we were nicer then. We were nice, kids and cities and trees were nice, everything … I don’t know who we are anymore and I’m starting not to care.’ It’s so awful, so painfully defeatist, but because that show travels backwards in time, it ends on the purity and simplicity of youthful expectation. Every time I hear those characters, now impossibly young and ignorant of all the failures and regrets to come, sing ‘It’s our heads on the block. Give us room and start the clock. Our time coming through! Me and you, pal, me and you!’ it makes me cry. Without fail. The same thing happens to me at the conclusion of Sunday in the Park with George, the painter’s subjects moving into their allotted positions, singing of ‘the cool blue triangular water on the soft green elliptical grass, as we pass through arrangements of shadows towards the verticals of trees forever ’.

That musical was probably his greatest masterpiece – although excellent cases can be made for Into the Woods, Company, Sweeney Todd, Follies, and for that daring shot in the temple, Assassins (1990) – mainly because it deals so profoundly with the act of creation itself. ‘Finishing the Hat’ was the only song Sondheim admitted to being ‘an immediate expression of a personal internal experience’, even though his denials around the title number in Anyone Can Whistle always felt too defensive to me, and it remains one of the greatest songs ever written for musical theatre. It is about making something, something true and beautiful and lasting, and about the sacrifices and the self-denial required from the artist in order to bring it to fruition. ‘Studying a face, stepping back to look at a face leaves a little space in the way like a window, but to see – it’s the only way to see.’

We Sondheim lovers will always be grateful for the fact that he did step back, creating a space between himself and the world. There are whole universes of human pain, joy, and yearning through that window; while he can no longer ‘give us more to see’, as Dot encourages George to do, he has given us so much already. Sondheim’s influence is all over Jonathan Larson’s Rent (1996), Trey Parker, Robert Lopez, and Matt Stone’s Book of Mormon (2011) and Lin Manuel-Miranda’s Hamilton (2015). It will continue to be felt for generations of theatre-makers to come. It might seem like the end of genius, the dimming of a great light, but that’s the wonderful thing about true artistry: it moves backwards as well as forwards in time. I shall always return to that ending in Merrily We Roll Along, which is also a beginning. ‘Something is stirring, shifting ground. It’s just begun.’

Vale, Mr Sondheim. And thank you.

This commentary is supported by the Copyright Agency’s Cultural Fund.