The Great Australian Play

A play begins its conversation with an audience well before the house lights go down. Marketing images, PR blurbs, interviews – they all launch the process of introducing the work, of situating it in the world. By opening night, the audience is primed. A good production slips seamlessly from the abstract to the real, maintaining a coherent identity from marketing copy to stage. The Great Australian Play, now playing at Theatre Works, promises a scathing indictment of the emptiness at the heart of our national mythology. Instead, it delivers a meandering portrait of a writer who is embarrassed by his own source material.

The source material, as it happens, is fantastic: In 1930, Harold Bell Lasseter strides into a union office with wild claims of a vast reef of gold hidden in the middle of Australia. Private investors fund a madcap expedition whose members finally realise that Lasseter is bullshitting them. They leave him in the desert where he starves to death, clutching a diary referring to the existence of the treasure.

This story is unusually rich, not just thematically. Here, there is much to unpack about Australia’s relationship with the country itself. The colonial relationship with the landscape is one of contest, of battle, of staring into emptiness with mistrust and contempt. Lasseter’s story evokes Australia’s weird way of turning inexperienced desperadoes into heroes – Burke and Wills, Sturt, bumbling around the interior, desperate to find something in the emptiness. It contains the constant neglect of Indigenous knowledge. There’s the desperation at economic downturn, the faith in riches hidden beneath the earth. And there’s the relationship of stories to landscape. Through stories, we inscribe the land. Our myths tell us where we belong, and where we don’t. Playwright Kim Ho has extensively referenced Patrick White’s 1958 description of ‘the Great Australian Emptiness’ in interviews about this work, only his third, after his previous script Mirror’s Edge won the 2017 Patrick White Playwright’s Award. Whereas The Great Australian Play might have correlated White’s disdain for Australian intellectual life with the colonialist presumption of Australia’s physical emptiness, it distracts itself with needless metatheatrical padding that serves only to blunt any critical argument it might contain. The Great Australian Play ties itself in knots trying to justify its own existence.

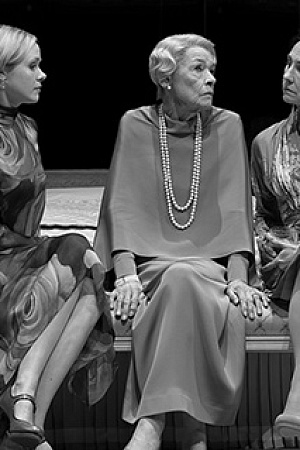

Sermsah Bin Saad and Tamara Lee Bailey in The Great Australian Play (photograph by Jack Dixon-Gunn)

Sermsah Bin Saad and Tamara Lee Bailey in The Great Australian Play (photograph by Jack Dixon-Gunn)

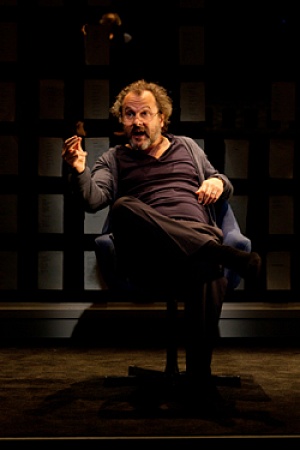

From the moments the lights go down, the production’s tone feels amorphous and uncertain. It’s a contrived opening: faux-horror, affectedly cinematic. In the darkness, a woman whispers about a nightmarish character called the Fidgeter. A man’s voice relates Lasseter’s fantastical story as Sermsah Bin Saad dances behind a black scrim. The voice over drones on and on for endless minutes. Tension seeps out of the theatre. By the time Bin Saad emerges from the curtain with a microphone, the play has lost its audience. It never quite gets them back.

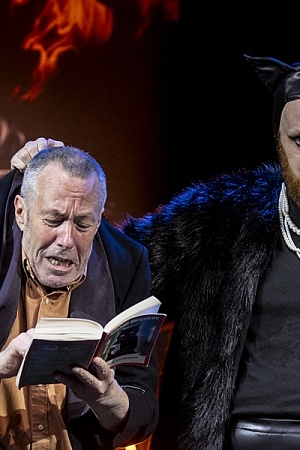

When the house lights snap on, the rest of the cast is scattered throughout the audience, reading feedback from a Screen Australia funding rejection. They haven’t been successful, despite Nick Cave and Warren Ellis’s ‘impressive’ support. Screen Australia will, however, fund a three-week development of the film in the outback. Though disdainful, the team accepts this grudgingly, shuffling onstage past the audience.

The curtains open on a red desert exterior, with two whiteboards in the dust. The writing team pitches ideas back and forth, wondering whether anyone will believe the story or care. Bin Saad, still in character as Lasseter, urges them on. They periodically assume the roles of the expedition party before resuming their bickering, interspersed with enigmatic monologues. They float increasingly ridiculous concepts for the film, including an excruciating Hamilton parody, before discovering that the story is already a play by Kim Ho, as well as a Stan Original series. The act ends with a baffling shift into non-naturalism, as Jessa Koncic pulls a pale dildo from an animal cage, strips to her bra, spits to lubricate the dildo, and then protractedly fucks the red earth with it. She then dons a fringed coat and takes on the role of the mythical Fidgeter, twitching her way to interval.

L-R: Tamara Lee Bailey, Sarah Fitzgerald, Sermsah Bin Saad, Daniel Fischer, and Jessica Koncic in The Great Australian Play (photograph by Jack Dixon-Gunn)

L-R: Tamara Lee Bailey, Sarah Fitzgerald, Sermsah Bin Saad, Daniel Fischer, and Jessica Koncic in The Great Australian Play (photograph by Jack Dixon-Gunn)

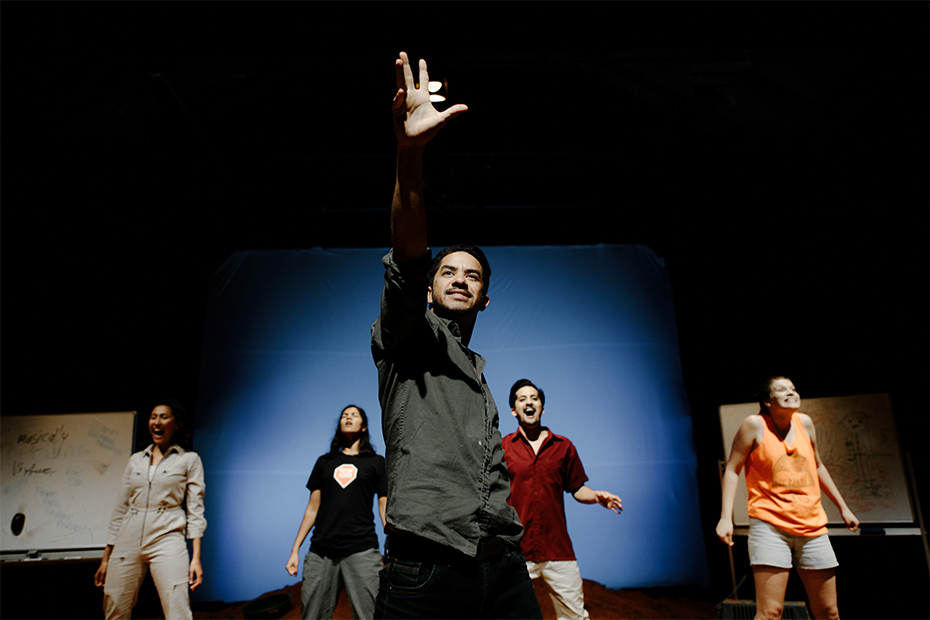

Act II feels like a separate production entirely. The curtains draw back to a parody of the classic well-made play, a twee family preparing for dinner, the arrival home of Lasseter (Bin Saad). He buys the renewed love of his sceptical family with gifts. The scene repeats, corrupting, across the act, interspersed with time-stretched versions of dated pop music and dreamlike snippets of scenes. The presents become a gun and a voucher for plastic surgery. The dinner is replaced with fast food. The son calls his mother a bitch. The Fidgeter twitches under the kitchen table. Instead of unpacking Australia’s mythological hang-ups with depth and wit, Ho has created his own myth, which Bailey relates. The Fidgeter is a cave-dwelling monster. Once he tells you his story, you will never be the same. This story could be the bones on which the production is hung. Instead, the more detail is added, the more the cogency of the metaphor breaks down.

In his writer’s notes, Ho thanks the many playwrights who advised on the script while he was at the VCA. This makes sense of the tone of The Great Australian Play: it feels as though it was written by committee. The script reveals his influences: he aims for Patricia Cornelius’ savage abjection in an awkward flirtation scene between Bailey and Koncic, as the latter squats to pee, and for Morgan Rose’s horrifying collisions of surrealism and the everyday in the interstitial moments in Act II. But Ho can never quite weave these modes into the body of the script and allow his characters to impact each other meaningfully or to find the monstrous within the real. The surrealist moments in the play come from what Ho describes as ‘writing from his subconscious’. Like most dreams, they fall apart under scrutiny. He comes up with terrific prompts: a woman converses with a sentient pokies machine; a man tries to pitch his script to a dead kangaroo. After creating these scenarios, though, Ho has no idea what to do with them. Its metatheatrics, too, feel dramaturgically confused. The filmmakers in Act I are stand-ins for Ho. When the playwright himself steps out of the audience to hurl abuse at Brett Whiteley’s painting of Patrick White, describing his misgivings about writing the work, the entire first act is rendered useless. This doubling proves nothing but frustrating. Attempting to convey its fear of telling a story, the production falls apart.

The play struggles, too, with its handling of Indigenous agency and storytelling. Sarah Fitzgerald points out that the Lasseter myth largely ignores the presence of Mickey, a Western Aranda stockman whom the expedition party referred to by ‘the N word’. She also advocates telling the story from the perspective of the land, an idea that is quickly shut down. Where the production might have pulled apart the conventions of the Lasseter story and gone after Mickey, or situated the land itself as a character, it simply shrugs and carries on. Sermsah Bin Saad’s casting as Lasseter feels equally uncomfortable. Having an Indigenous actor inhabit the narrative of a notorious white conman leading a doomed mission into the Australian interior should spark urgent political conversations within the production. Instead, the decision feels thematically limp.

Jessica Koncic, Sarah Fitzgerald, Tamara Lee Bailey, Sermsah Bin Saad, and Daniel Fischer in The Great Australian Play (photograph by Jack Dixon-Gunn)

Jessica Koncic, Sarah Fitzgerald, Tamara Lee Bailey, Sermsah Bin Saad, and Daniel Fischer in The Great Australian Play (photograph by Jack Dixon-Gunn)

Above all, the production lacks precision. Pace is a constant problem; scenes drag on, monologues drone. The huge Theatre Works stage, which should lend an epic physical presence of the landscape, instead begins to overwhelm it. Ho describes the production as ‘David Lynch meets Red Dog’. But where Lynch’s work hinges on the collision of the eldritch and the ordinary, The Great Australian Play struggles to operate across multiple modes. It leaves little room for stagecraft. Ho’s work, particularly in Act I, is all talk, all exposition. It tells whenever it ought to show. The script would have benefitted hugely from an experienced dramaturg, as well as from a director who could meet Ho’s wordiness with crisp staging.

The Great Australian Play contains the possibility of an extraordinary revisionist western, tearing apart the patriarchal, colonialist traditions of storytelling, reintroducing the theatre to the complexity and richness of story that comes from the country itself. It aims at the kind of genre-exploding Australian gothic that Sisters Grimm produced so cannily with The Sovereign Wife (MTC, 2013). Instead, it is so busy trying to subvert conventions that it never gets around to making a statement. In interviews about the script, Ho admits to being embarrassed by the earnestness of his previous work. A little of that earnestness would have served The Great Australian Play well. It is so determined to be cynical that it never manages to be subversive. It ignores the real fascination of the Lasseter story and, in doing so, fails to convey anything other than its own fear of failure.

The Great Australian Play continues at Theatre Works until 29 February 2020. Performance attended: February 20.