Stravinsky Double Bill (Melbourne Symphony Orchestra) ★★★★

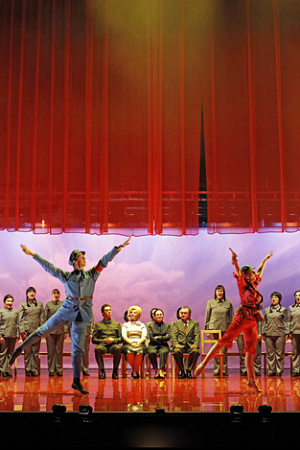

Midwinter Melbourne resounded last week to Igor Stravinsky’s promise of spring, in two works that trace the seasonal drama of life, death, and rebirth. The Rite of Spring (1913) is a young man’s spectacular evocation of the exhilaration and terror of spring in ancient Russia, while Perséphone (1934) is a more reflective response to the endless cycle of the seasons, written by an older and more spiritual composer by then in permanent exile. Although both were originally conceived as choreographic works, this concert performance would surely have been sanctioned by the composer. The Rite of Spring quickly transcended the scandal of its stage première when relaunched in the concert hall the following year, and in 1934 Stravinsky openly acknowledged that Perséphone’s ‘musical autonomy is in no way affected by the absence of a stage spectacle’, and distanced himself from the infelicities of its first production.

Andrew Davis and the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra deserve our gratitude for reviving Perséphone, a work that was unfashionable in the postwar decades when high modernism held sway, and was even disavowed by its composer. Sitting at the midpoint of Stravinsky’s career, Perséphone, Cerberus-like, faces both past and future, its hybrid style described by Hans Keller as ‘neo-classical, neo-preclassical, and even pre-archaic’. In it we hear echoes of Stravinsky’s music from the stylised nationalism of the late Russian works to the eclectic borrowings and ritualism of Oedipus Rex (1927) and the Symphony of Psalms (1930), even as it foreshadows his late neoclassical operatic masterpiece The Rake’s Progress (1951).

A melodrama in three tableaux based on André Gide’s reinterpretation of Homer, Perséphone was originally intended for recitation, mime, and ballet with solo tenor, adult, and children’s choruses, and orchestra. This unusual configuration provided the platform for fading star Ida Rubinstein to speak and mime the title role of the ancient Greek goddess of spring. Persephone’s journey from pastoral idyll to the underworld and back is narrated by the priest Eumolpus (a tenor), while multiple choruses impersonate nymphs, shades of the dead, and the mortals who welcome Persephone’s rebirth and restoration of the spring.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.