Death of a Salesman

Seventy years ago, on 10 February 1949, Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman premièred on Broadway to rapturous acclaim. Miller’s intention in writing the play, he recalls in his autobiography, Timebends (1987), was not to put ‘a timebomb under capitalism’ – as one outraged woman accused on opening night – but rather to expose a ‘pseudo life that thought to touch the clouds by standing on top of a refrigerator, waving a paid-up mortgage at the moon’. It’s ironic that a country that did so much to articulate and sell the American Dream – perhaps best précised by Hap Loman as the fight to come out ‘number one man’ – should give birth to one of literature’s biggest losers. But after hundreds of productions of Death of a Salesman around the world, Miller’s anti-hero – ‘a joker, a bleeding mass of contradictions, a clown’ – has been found to be representative everywhere, in every system, of ourselves.

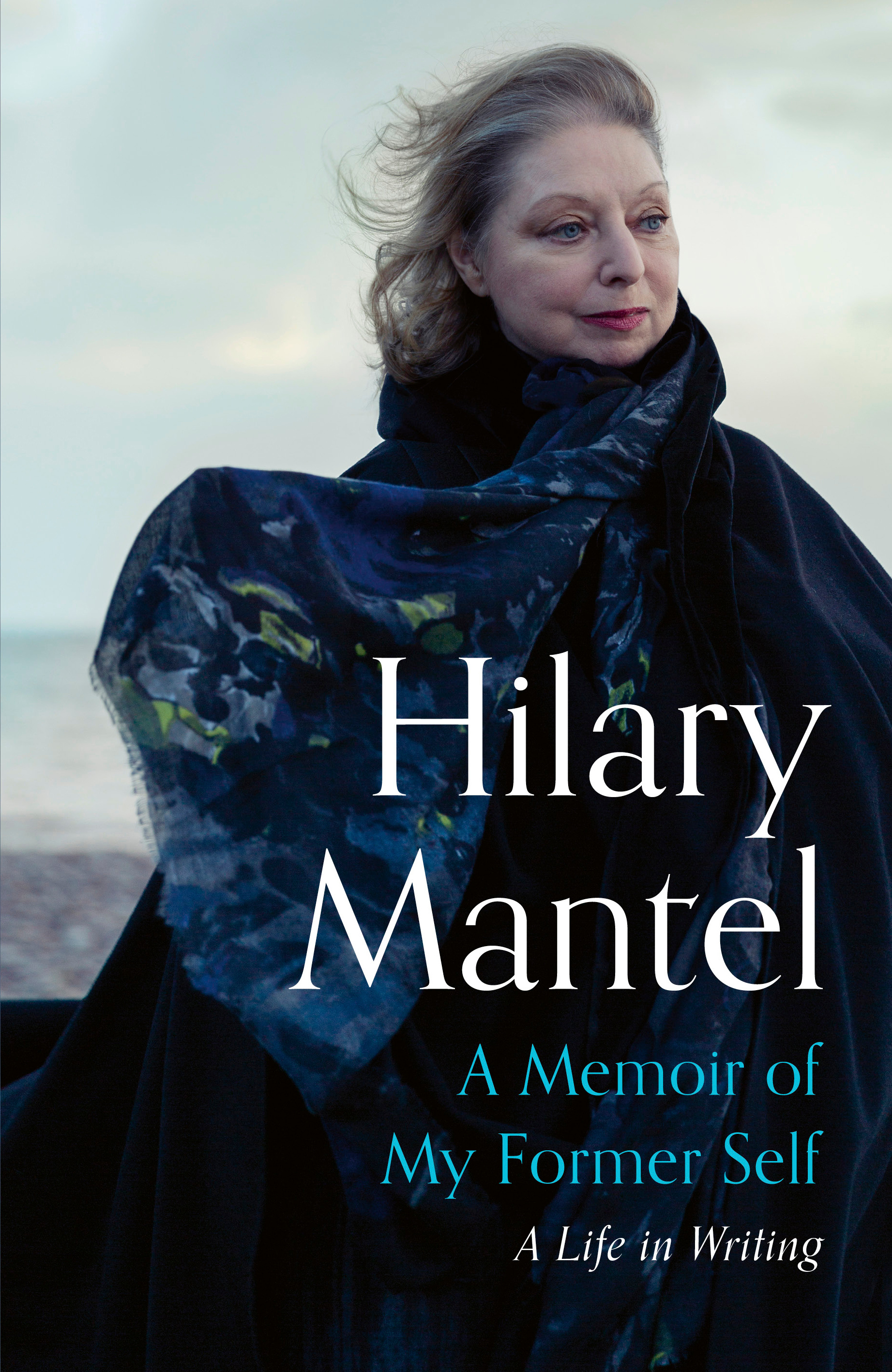

Jackson McGovern Peter Kowitz, and Thomas Larkin in Death of a Salesman (photograph by Peter Wallis)

Jackson McGovern Peter Kowitz, and Thomas Larkin in Death of a Salesman (photograph by Peter Wallis)

I wouldn’t be alone in thinking Miller’s writing lacks poetry. His plays give little pleasure in the reading, and his most famous lines – ‘he’s liked, but he’s not well liked’ or ‘attention must be paid’ – sound bland or even naff removed from context. And yet Death of a Salesman, properly staged, as it is in Jason Klarwein’s anniversary production, consistently delivers one of the most enthralling and emotional experiences in live theatre. In honouring the play as the period piece it has become, Klarwein resists a heavy interpretative overlay of his own and relies on the dramatic vigour of Miller’s characterisation to draw us into 1940s America. Sound designer Justin Harrison sets the mood with the melancholic tune ‘We Three’ from The Ink Spots – ‘We three, we’re all alone / Living in a memory / My echo, my shadow, and me’ – suggestive of Willy Loman’s lonely life on the road with only the voices inside his head for company.

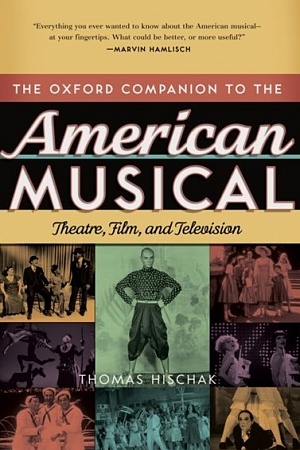

The set, intelligently conceived by Richard Roberts, zeroes in on the rudiments of a family home: a kitchen and the marital bed. At sixty-three, Willy is kicking and flailing down a greasy slide to oblivion. He would say or do anything to make a sale, but nobody is listening; they haven’t been for years, and his commissions have hit the skids. Desperate and obsequious, Willy habitually plagiarises the kind of Depression-era optimism found in Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People. Sales, he knows, requires constant impersonation, but Willy has lost himself in a lifetime of fantasy and lies.

Peter Kowitz’s Willy – among the best I’ve seen – swells and shrinks inside his suit as bravado augments his physique before conceding to the humiliation of arriving, totally unprepared, at his obsolescence. He’s just paid off the car, but it’s on its last legs. ‘Once in my life I would like to own something outright before it’s broken!’ he says. ‘I’m always in a race with the junkyard!’ He has one more payment to make on his mortgage, but it doesn’t look like he can make it. ‘They time things,’ he observes, ‘so when you finally paid for them, they’re used up.’ Fortunately for Willy – or at least it appears fortunate inside his rapidly deteriorating mind – he has a ‘proposition’ in the form of an insurance policy that shines like a diamond in the dark jungle, if only he’d reach out his hand. Willy knows exactly how much a man’s life is worth: for him it’s a head price of $20,000.

The set of Death of a Salesman (photograph by Peter Wallis)

The set of Death of a Salesman (photograph by Peter Wallis)

Although Miller’s men often struggle with their consciences, his women rarely do. They’re either dangerous temptresses, like Abigail Williams in The Crucible (1953), or maternal saints like Willy’s wife, Linda. But Angie Milliken bestows Linda with an emotional complexity that has us question the naïveté and purity of her actions: does Linda really think she is protecting her husband when she returns to him the instruments – gas pipe, car keys – of his suicide attempts? It’s not clear exactly what Linda considers her shiny prospect to be, but her knack for prodding Willy to his doom nevertheless propels the narrative along its deadly tracks.

Willy’s thirty-something sons, Biff and Hap – played by Thomas Larkin and Jackson McGovern – are described by their mother in a moment of rage-fuelled lucidity as an ingrate and a philandering bum. Single and serially unemployed, they show us that the failure-to-launch syndrome existed long before Gen Y males preferred to live as shut-ins playing video games rather than venture out for a driver’s licence and a job. When Hap vows at his father’s graveside to marry and to continue Willy’s dream to come out number one man, we suspect that Hap, too, is in a race with the junkyard. At least Biff has seen what a ridiculous lie his whole life has been, which might be just enough to save it.

Death of a Salesman is being performed by Queensland Theatre at the Playhouse from 9 February to 2 March 2019. Performance attended: February 15.

ABR Arts is generously supported by The Copyright Agency's Cultural Fund and the ABR Patrons.