Masters of Modern Art from the Hermitage (Art Gallery of New South Wales)

On 6 March 1948 – a mere seventy years ago – the paintings that comprise this stellar exhibition of ‘Modern Art’ from St Petersburg’s great cultural repository, the State Hermitage Museum, were condemned in a decree by the Council of Ministers of the USSR as ‘the bourgeois art of Western Europe, bereft of ideas, anti-national, formalist, and of no interest for the progressive education of the Soviet public’ (quoted in the newly published The Collector: The story of Sergei Shchukin and his lost masterpieces by Natalya Semenova with André Delocque [Yale University Press/Footprint, $59 hb].)

The ministers who issued decree number 672 are long forgotten. Not so the canvases of Cézanne, Monet, Sisley, Vuillard, Vlaminck, Matisse, Derain, Rousseau, Redon, Picasso, and Kandinsky, or of the other twenty-five artists whose works, in their fascinating and divergent ways, make this exhibition so compelling. Bereft of ideas? The sixty-five paintings in the Hermitage exhibition are a visual embodiment of the great flux of ideas in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries – that pivotal time we still call ‘modern’.

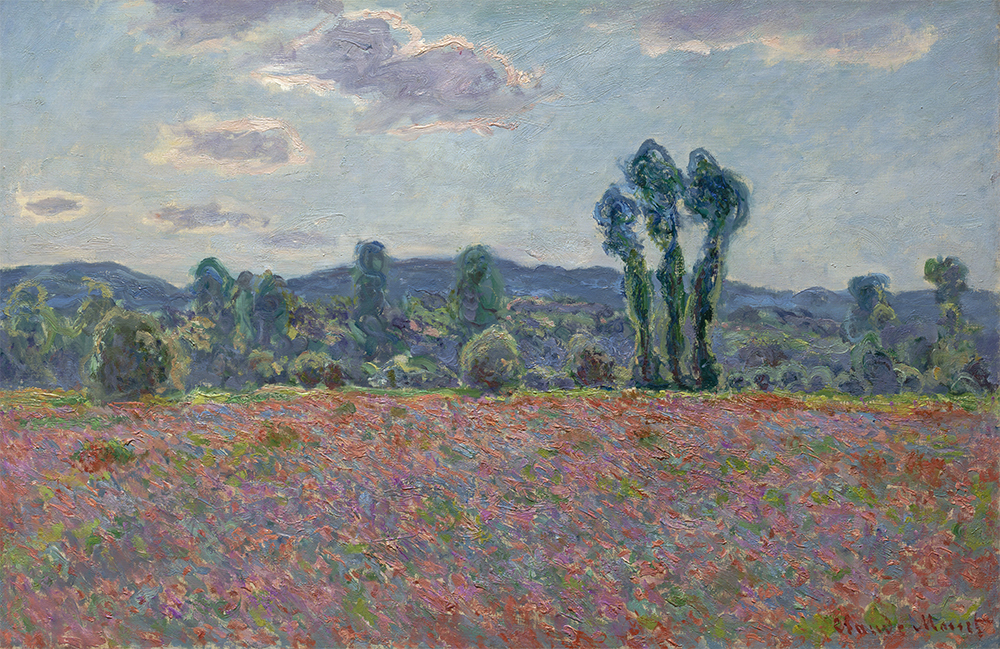

The exhibition itself is a sensuous delight. Turn the corner of one of its rooms and you come face to face with the jewel-like vibrancy of Odilon Redon’s Woman asleep beneath a tree (1900–1). No reproduction could do justice to its pulsating red, mauve, orange, and blue juxtapositions. It is a small painting, but unforgettable. As are the Cézannes in the room before – his still life Fruit (1879–80) with its faceted mountain of a white napkin playing foil to the sprawl of orange citrus, and the monumental energy of his Large pine near Aix-en-Provence (1895–97). The third Cézanne, The Banks of the River Marne (1888) is complemented by AGNSW’s own Banks of the Marne, painted in the same year (not in the exhibition catalogue, but a welcome adjunct). These early rooms of the exhibition – which also show Sisley’s gently vigorous (in the horizontal brushstrokes) Windy day at Veneux (1882), Monet’s Poppy Field (1890–91), and Waterloo Bridge, effect of fog (1903) – would be riches enough for one visit. But this exhibition is not a blockbuster cavalcade of great and famous paintings. It is a thought-provoking window into European art and socio-political history, encapsulated in the story of two extraordinary Russian entrepreneurs, the textile importer Sergei Shchukin and manufacturer Ivan Morozov, and the spectacular collections of the art of their times that they gathered around them.

Paul Cézanne, Fruit, 1879/80, oil on canvas, 46.2 x 55.3 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Inv GE 9026 (photo: © The State Hermitage Museum 2018, Pavel Demidov and Konstantin Sinyavsky)

Paul Cézanne, Fruit, 1879/80, oil on canvas, 46.2 x 55.3 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Inv GE 9026 (photo: © The State Hermitage Museum 2018, Pavel Demidov and Konstantin Sinyavsky)

Two thirds of the paintings in Masters of Modern Art from the Hermitage were acquired in France and brought to Russia to be displayed in the grand Moscow houses (palaces) of Shchukin and Morozov. Both astute businessmen (‘Muscovite capitalists’, in the words of decree 672), they had the support and often the active collaboration of their respective siblings. But the two were the prime movers, and it is through their collections, put together over little more than a pressured decade, that one can read the temper of their revolutionary times.

The local critical climate was sometimes receptive, more often vitriolic: Shchukin was deemed mad when he displayed Matisse and dangerous when he took up Picasso. But collecting is a risky enterprise, and Shchukin and Morozov faced more than market fluctuation: they were building their troves of art before and during the 1905 revolution and through family tragedies – deaths, suicides, and separations. Both made arrangements to leave their collections, which they had already turned into museums, to the state, but the precise details of their philanthropy, and their wishes regarding the housing and management of their treasures, were lost in the winds of revolution. The collections were nationalised. Fortunately, the Council of People’s Commissars, in a decree signed by Lenin in 1918, understood rather better than their 1948 counterparts the value of the art they had requisitioned. It was deemed ‘an exceptional collection of European masters, mostly French’ and ‘of major artistic value … for the education of the people’. (Abandon irony all ye who toy with ideologies …)

In the harsh years that followed, the paintings in the collections were variously moved, parcelled out, or stored. Their sale was mooted – revolutions prove expensive in the aftermath. Yet they survived and remained in Russia. In our time, when the blowing up of ancient monuments or the burning down of museums have become barbaric habits, this survival looks almost miraculous. It does attest, however, to the complexity of the twentieth-century Russian experience and to the folly of historical stereotyping and generalisation. The very existence of those works in Moscow in the early 1900s animated the Russian avant-garde. And when, post the ‘thaw’ that followed the 1956 Twentieth Congress of the Communist Party, they began to be displayed again, they were as immediate and potent an influence as they had been in 1905, even if few of the artists and enthusiasts who gathered to argue about or take inspiration from them could remember their provenance, or the adventurous Moscow merchants who had poured not just their riches but wholehearted passion into the business of collecting – for themselves and for posterity.

Claude Monet, Poppy field, France, 1890/91, oil on canvas, 61 x 92 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Inv GE 9004 (photo: © The State Hermitage Museum 2018, Pavel Demidov and Konstantin Sinyavsky)

Claude Monet, Poppy field, France, 1890/91, oil on canvas, 61 x 92 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Inv GE 9004 (photo: © The State Hermitage Museum 2018, Pavel Demidov and Konstantin Sinyavsky)

Ivan Morozov’s collection, particularly as represented in this exhibition, focuses on the earlier works of the tumultuous turn-of-the-century period. It seems odd, now, to think of Cézanne as revolutionary, although his influence on the compositional elements of art that followed him are evident in the sublime landscapes: his Large pine near Aix-en-Provence blends block brushstrokes with the linearity of branches. An obsession with the geometry of form is evident even in the graphite and watercolour study of the same subject helpfully included in the catalogue. Picasso and Cubism sound in the wings, and Cézanne’s influence is like a ground bass in the exhibition. The Fauvist exuberance of Maurice de Vlaminck’s View of the Seine (1906), given to Morozov by his Paris Dealer in 1908, has transmuted into a stately Cézanne-inflected landscape (Small town on the Seine, 1909), acquired by Shchukin in 1910.

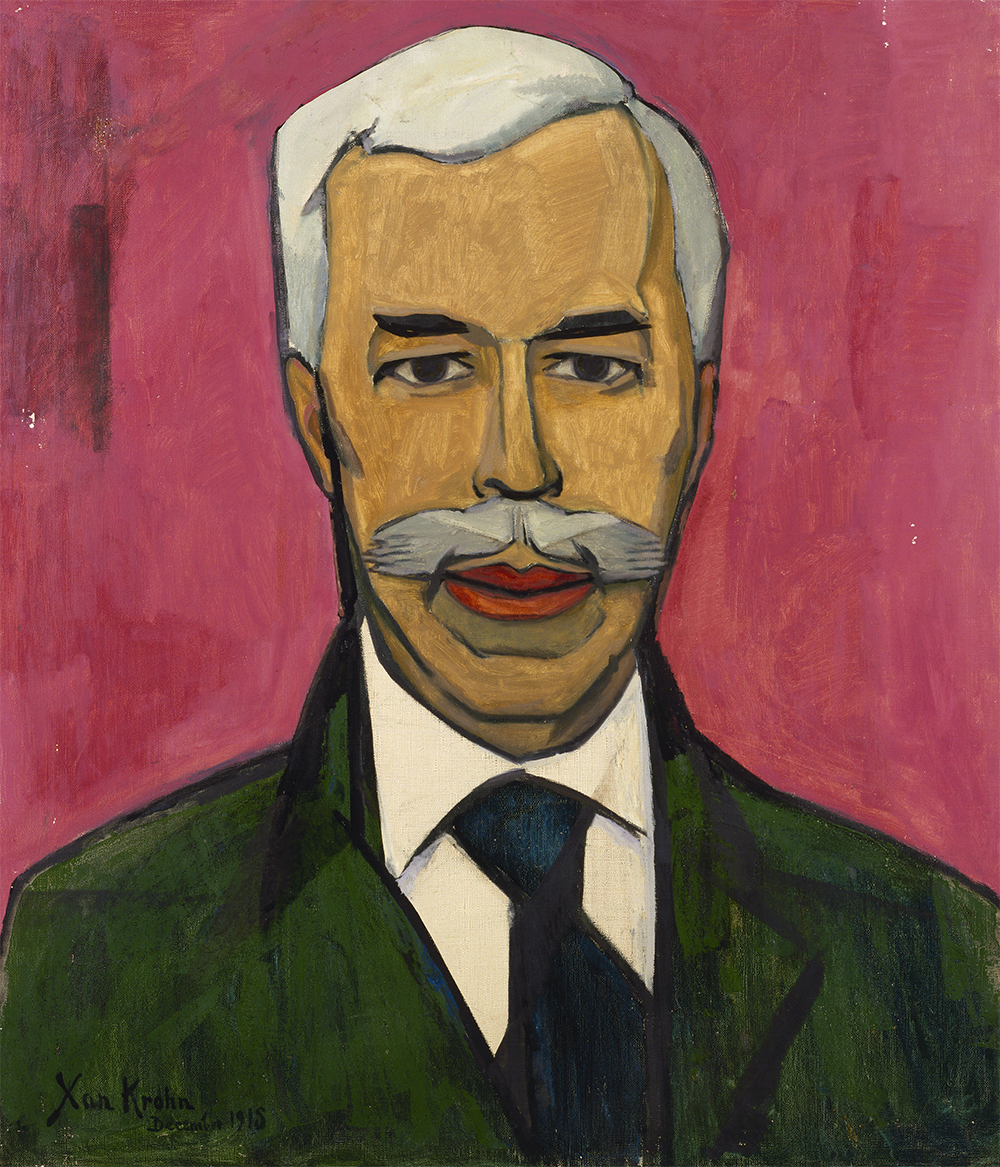

Sergei Shchukin was an unlikely patron of the arts. He was a third son and, like the Emperor Claudius, a stutterer, at least until his merchant father, with an eye for his most likely successor, had him educated out of his affliction. Shchukin’s sometimes-awkward demeanour and hesitant speech disguised formidable business acumen, and he was a shrewd negotiator. But he was also, in the face of art, a Russian Romantic, completely immersed in the sensory experience. Colour had a profound effect on him. Little wonder Matisse moved him to eloquence: ‘For me Matisse is above all the rest … closest to my heart … His work is a festival of exultant colour.’ There is a poignancy about the one portrait of Shchukin shown in the exhibition. Matisse had been working on a portrait, but all that remains of it is a beautiful sketch – the sittings were broken off when his patron had to rush back to Moscow upon the death of his brother. Shchukin later commissioned the young Norwegian Christian Krohn to paint two portraits. They are both stark and restrained, their roots in Cubism evident. Only the colour – a vibrant pink glowing behind the merchant’s head – hints at Shchukin’s passion and commitment to the art of his time. In this exhibition, shown as the one explosion of colour in a black-and-white photo mock-up of a room in Shchukin’s mansion, it is profoundly moving.

Christian Cornelius Krohn (Xan Krohn), Portrait of Sergey Shchuki'n, 1915, oil on canvas, 97.5 x 84 cm The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Inv GE 9090 © Estate of Christian Krohn/BONO.Copyright Agency, 2018 (photo: © The State Hermitage Museum 2018, Vladimir Terebenin, Leonard Kheifets and Yuri Mololkovets)

Christian Cornelius Krohn (Xan Krohn), Portrait of Sergey Shchuki'n, 1915, oil on canvas, 97.5 x 84 cm The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Inv GE 9090 © Estate of Christian Krohn/BONO.Copyright Agency, 2018 (photo: © The State Hermitage Museum 2018, Vladimir Terebenin, Leonard Kheifets and Yuri Mololkovets)

Shchukin’s bravest Matisse commissions, Dance (1909/10) and Music (1910) (nudes, explosive colour), are not shown in this exhibition, but large projections of them get an outing in the accompanying multimedia installation by Saskia Boddeke and Peter Greenaway.

This is, strictly, a Hermitage show, not a retrospective of the Shchukin and Morozov collections, though there is thematic unity in that all the art on show had to run the gauntlet of the twentieth century’s ideological strictures. Kandinsky, who completes the exhibition in a grand symphony of colour, had to have his paintings kept safely out of sight for years. It is a pity that none of his one-time partner Gabriele Münter’s work is not on show as well. The one work by a woman in the exhibition is the splendid Sonia Delauney-Terk’s Prose of the Trans-Siberian Express (1913).

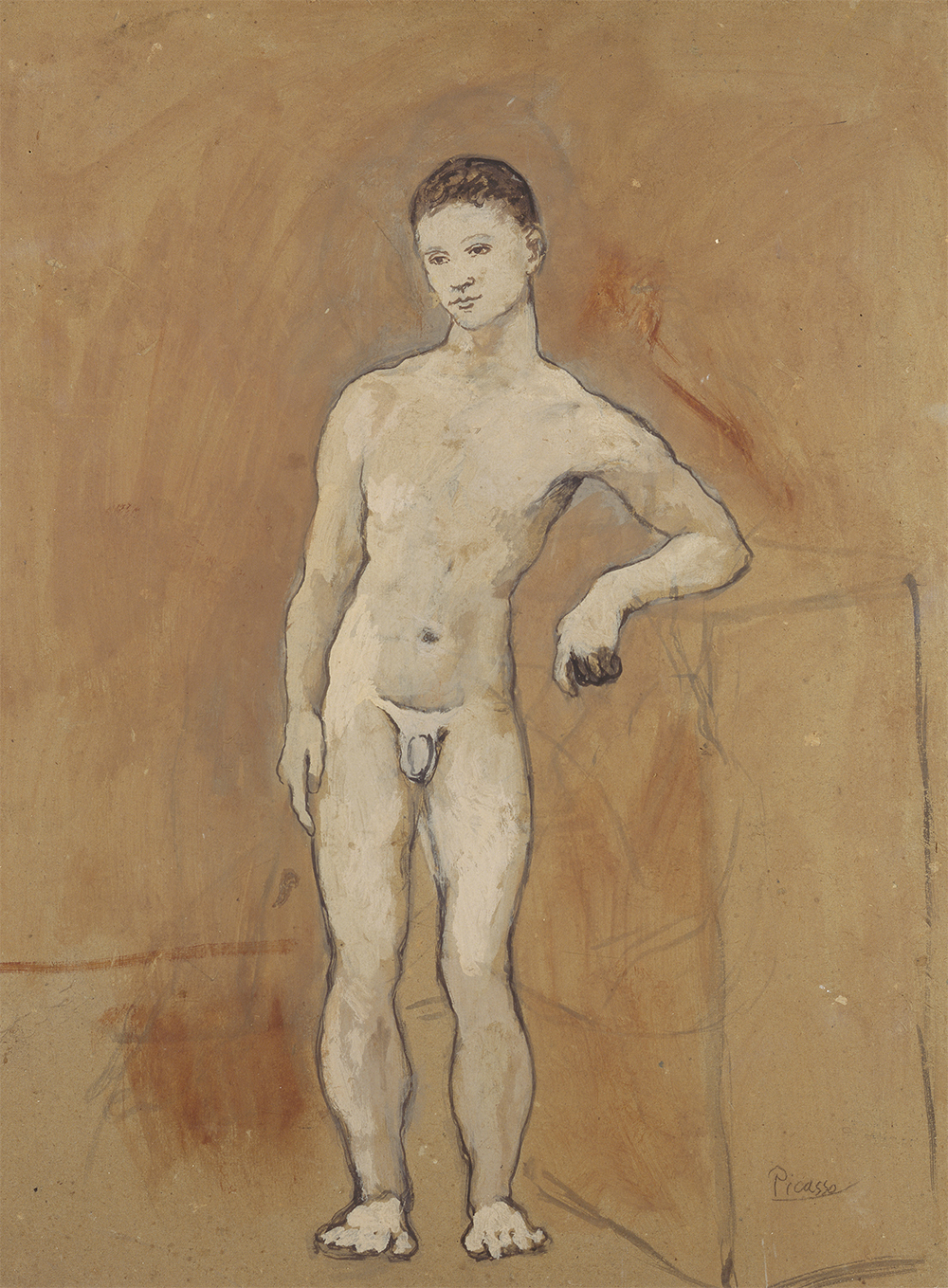

There are many other treasures: Edouard Vuillard’s intimate interiors of children and men and women in a domestic room; André Derain’s various experiments with Fauvist colour and then restrained landscapes; Georges Roualt’s uncompromisingly dark portraits of two prostitutes, Girls (1907), and a peerless Nude boy (1906) by Picasso, among the more Cubists works that the far-sighted Shchukin dared to bring into his home. And there are some dull paintings and some surprises – a Morandi that has been strained through de Chirico, and two Bonnards that only hint at what else he would achieve.

Pablo Picasso, Nude boy, 1906, gouache on card, 67.5 x 52 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Inv OR 40777 © Pablo Picasso/Succession Pablo Picasso/Copyright Agency 2018 (photo: © The State Hermitage Museum 2018, Vladimir Terebenin, Leonard Kheifets and Yuri Mololkovets)

Pablo Picasso, Nude boy, 1906, gouache on card, 67.5 x 52 cm, The State Hermitage Museum, St Petersburg, Inv OR 40777 © Pablo Picasso/Succession Pablo Picasso/Copyright Agency 2018 (photo: © The State Hermitage Museum 2018, Vladimir Terebenin, Leonard Kheifets and Yuri Mololkovets)

While international politics might make one despair, it is heartening to know that Michael Brand, Director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, is a member of the Hermitage’s international advisory committee and, with the Hermitage, is committed to bringing the intellectual influence as well as the aesthetic pleasures of art to city and regional communities in both countries. Soft diplomacy at its best.

The exhibition catalogue is an education in itself, as well as a visual delight. If you want a Cook’s tour of twentieth-century political history as reflected in art, or in Impressionism, Expressionism, Fauvism, the Nabis, the Symbolists, Cubism, or in any of the other subdivisions of Modernism, this Masters of Modern Art from the Hermitage exhibition is an exhilarating place to start.

Masters of Modern Art from the Hermitage is being exhibited at the Art Gallery of New South Wales from 13 October 2018 to 3 March 2019.

ABR Arts is generously supported by The Copyright Agency's Cultural Fund and the ABR Patrons.

Book referred to in this review:

The Collector: The story of Sergei Shchukin and his lost masterpieces

by Natalya Semenova, with André Delocque,

translated by Anthony Roberts

Yale University Press (Footprint), $59.00 hb, 304 pp, 9780300234770