Creditors (State Theatre Company) ★★★

August Strindberg thought Creditors, which premièred in its original Swedish in Copenhagen in 1889, his ‘most mature work’. Sitting alongside the more often performed The Father (1890) and Miss Julie (1889) in the playwright’s middle, ultra-naturalistic period, the play is an attempt to theatricalise ‘soul murder’, an idea – one that fascinated both Strindberg and his contemporary Henrik Ibsen – that emerged in the psychiatric literature of the late-nineteenth century, defined as the purposeful depriving of a person’s basic reason to live. In his 1887 essay ‘Soul Murder’, in part a response to Ibsen’s play Rosmersholm (1886), Strindberg wrote that ‘there is nothing so destructive to the thinking process as shattered hopes, and a highly developed form of this torture can induce insanity’. Is it possible, Strindberg wanted to know, for someone sufficiently ruthless to drive another weaker-willed person into submission, and, ultimately, to kill them?

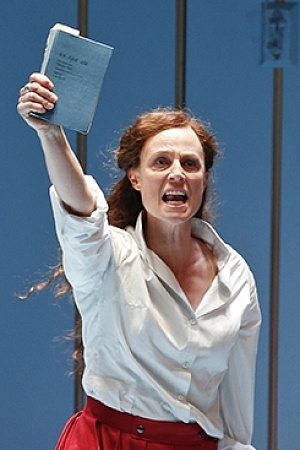

In Creditors, this dynamic is mapped onto the relationship between the older, Machiavellian Gustav (Peter Kowitz) and the young, impressionable painter-turned-sculptor Adolph (Matt Crook). While the original play’s setting is a seaside hotel, in Duncan Graham’s contemporised version, Adolph and his wife Tekla (Caroline Craig) are holed up in a sort of health retreat in the Australian bush (there is no mobile phone service and, unlike in the later psychological dramas by Eugene O’Neill, Edward Albee and others that somewhat resemble Creditors, emotions are strictly water- rather than alcohol-fuelled).

Under Gustav’s cloying watch, Adolph is sculpting a rather modernist, headless bust with oversized breasts, while Tekla – a novelist and, unbeknown to Adolph, Gustav’s former wife – is attending a nearby writers’ festival. Iago-like, Gustav persuades the highly strung Adolph that not only is he ‘pussy-whipped’ to the detriment of his art, but also that his wife is unfaithful, and that – in another nod to Shakespeare’s Othello – he is on the verge of epilepsy. But where Iago’s motives are famously opaque, Gustav’s are clear enough: revenge for Tekla’s leaving him, and for Adolph’s usurpation of what he believes to be rightly his.

Continue reading for only $10 per month. Subscribe and gain full access to Australian Book Review. Already a subscriber? Sign in. If you need assistance, feel free to contact us.