BPM (Beats per Minute) ★★★★★

BPM, or 120 battements par minute, to give its more expansive French title, is not the first film to be made about the charismatic activist group AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, better known as ACT UP, but it is the most lyrical piece of cinema so far to have emerged from ACT UP’s history. ACT UP, founded in New York, in 1987, has long been recognised for its direct actions – occupying the New York Stock Exchange, for instance, in protest at the prohibitive price of early AIDS drugs – and for its media-savvy deployment of graphics and slogans. The visual power of the group’s activities easily lends itself to filmmaking, and two relatively recent documentaries, How to Survive a Plague and United in Anger, both released in 2012, focus on the activities of ACT UP’s original branch, in New York. BPM departs from these in being a dramatisation, and in looking outside the United States to the work of ACT UP Paris during the early 1990s.

It’s a young crowd, for the most, that fills the scenes of BPM, and in particular the weekly ACT UP meetings that constitute the narrative spine of the film. Some of the activists are HIV-positive, but not all; the majority are gay men, though not all. One haemophiliac teenager, Marco (Théophile Ray), who has contracted HIV through a contaminated blood transfusion, attends the meetings with his mother, Hélène (Catherine Vinatier). A couple of gay women, diplomatic Eva (Aloïse Sauvage) and passionate Sophie (Adèle Haenel), are central to the group’s debates and organising. Thibault (Antoine Reinartz), the group’s HIV-positive chairperson, is focused on medical and pharmaceutical issues pertaining to AIDS treatment, which brings him into conflict with group members who wish to direct their energies towards wider structural issues relating to AIDS prevention, including prison reform and sex education. There is particular friction between Thibault and Sean (Nahuel Pérez Biscayart), a radical so in thrall to his own sense of urgency that he rarely waits his turn to speak. Caught somewhere between these two is Nathan (Arnaud Valois), a new ACT UP member, whom both Thibault and Sean have their eye on.

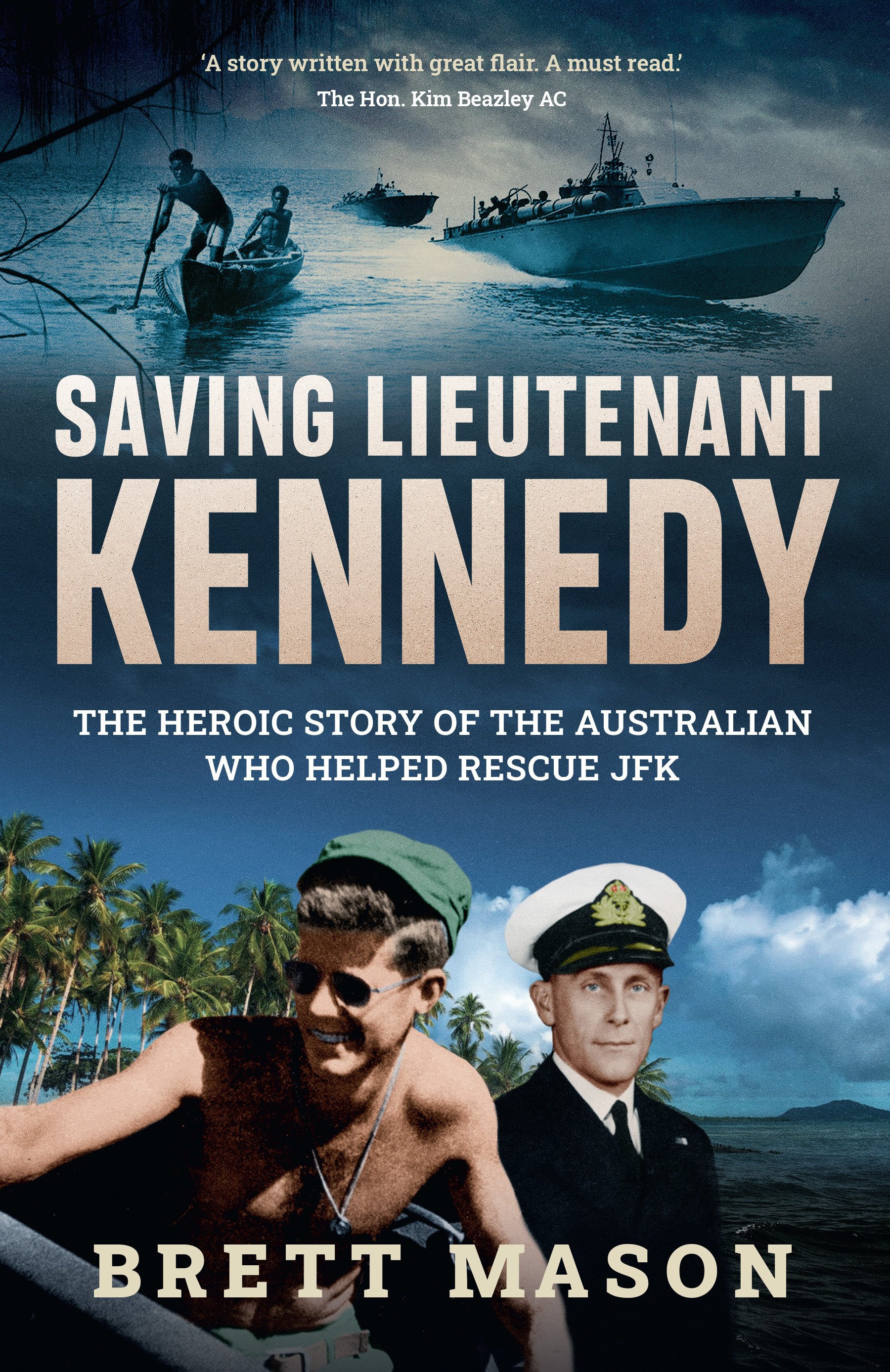

Nahuel Pérez Biscayart in BPM (Beats per Minute) (Madman Entertainment)

Nahuel Pérez Biscayart in BPM (Beats per Minute) (Madman Entertainment)

BPM’s director, Robin Campillo (The Class, Eastern Boys), and co-writer, Philippe Mangeot, were both members of ACT UP Paris during their twenties, and their intimate knowledge of the group’s dynamic is evident in every scene. So many fictional films that deal with political activism do so maladroitly, splicing in sentimental heroes where there were none, or conjuring neat narrative resolutions out of the tangle of organising as it happened. Not so the makers of BPM, who understand that, in this instance, the collective is paramount and that history is made from the mess of activism, with organisers working side by side, and day by day, without anyone possessing the benefit of clairvoyance. The ensemble of actors, too, is committed to the complexity of this milieu, in which it is possible to be righteous and petulant, ardent and bored, honest and self-deluding within the space of one meeting or protest, let alone over the course of a life. They hold themselves like young activists do, as if their anger made them sexy, which is the truth.

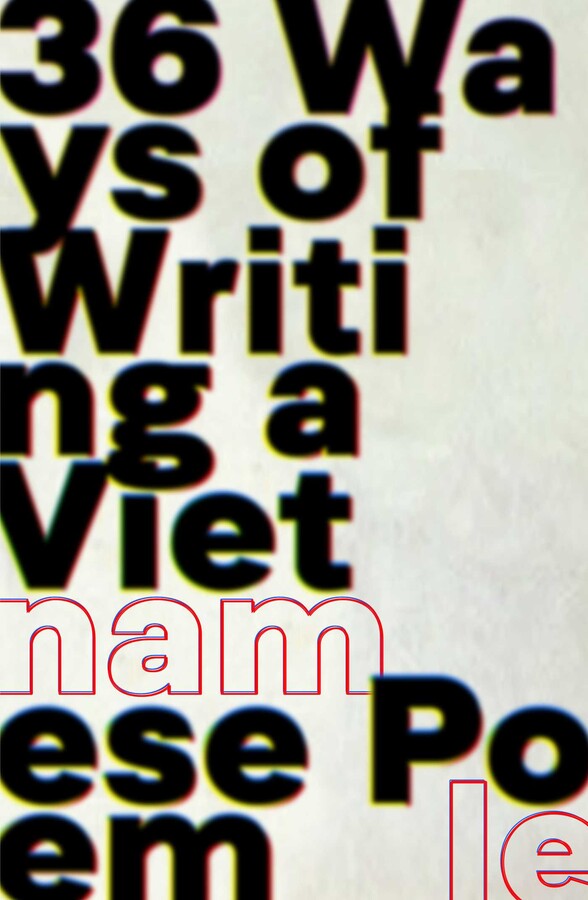

Arnaud Valois in BPM (Beats per Minute) (Madman Entertainment)

Arnaud Valois in BPM (Beats per Minute) (Madman Entertainment)

As the film moves fluidly between protests, meetings, club nights, and affairs, with the camera for the most part close but unobtrusive, and sound often transposed from one scene to another, we are left with the impression of a time and a place in which nothing, not even death, seems inevitable. All is open to possibility, contestation, and commingling: sex scenes are opportunities for political discussion, and protests a space for flirtation. Disagreements are erotic. Friendships can be strategic. Loving is activism, and so is grieving. In one affecting scene, the political funeral of an ACT UP member – his procession staged in the street, as a protest march – is intercut with archival footage of ACT UP actions, and with a voiceover memorialising the deaths of those who took part in the 1848 Revolution in France, more than a century earlier. So the work of ACT UP is contextualised within a long history of uprisings. The rebellion of the group is not an exception, even if the ardency of these activists might make them exceptional in particular moments.

BPM narrows somewhat in its second act, as Sean’s health deteriorates and his fear of dying makes him volatile, prone to lashing out at those who try to love him. Nathan is tender with him; Thibault, less so. Biscayart, as Sean, conveys the wounded egotism of a young man facing mortality all too soon, impatient with nearly everyone and everything. He is stubborn, vulnerable, exasperating, exhausted, human; living his politics, as another activist comments, ‘in the first person’. In the film’s most audacious shot, he dreams of a blood-red Seine, the terrible wastage of AIDS washing up at the feet of the general public.

Just as the film seems in danger of closing in too far on this one character, it opens up again, with the group reconstituting itself in the most devastating of circumstances. The final scenes return to the pace and scope of the film’s beginning, juxtaposing sex and protest, dancing and grief, only here these things don’t feel in conflict, but in concert. The one-hundred-and-twenty beats per minute of BPM’s French title refers not only to the human heartbeat, but to the pulse of house music that soundtracks these characters’ lives, and their loves – a constant rhythm at the centre of this brave, intricate, and perfectly imperfect film.

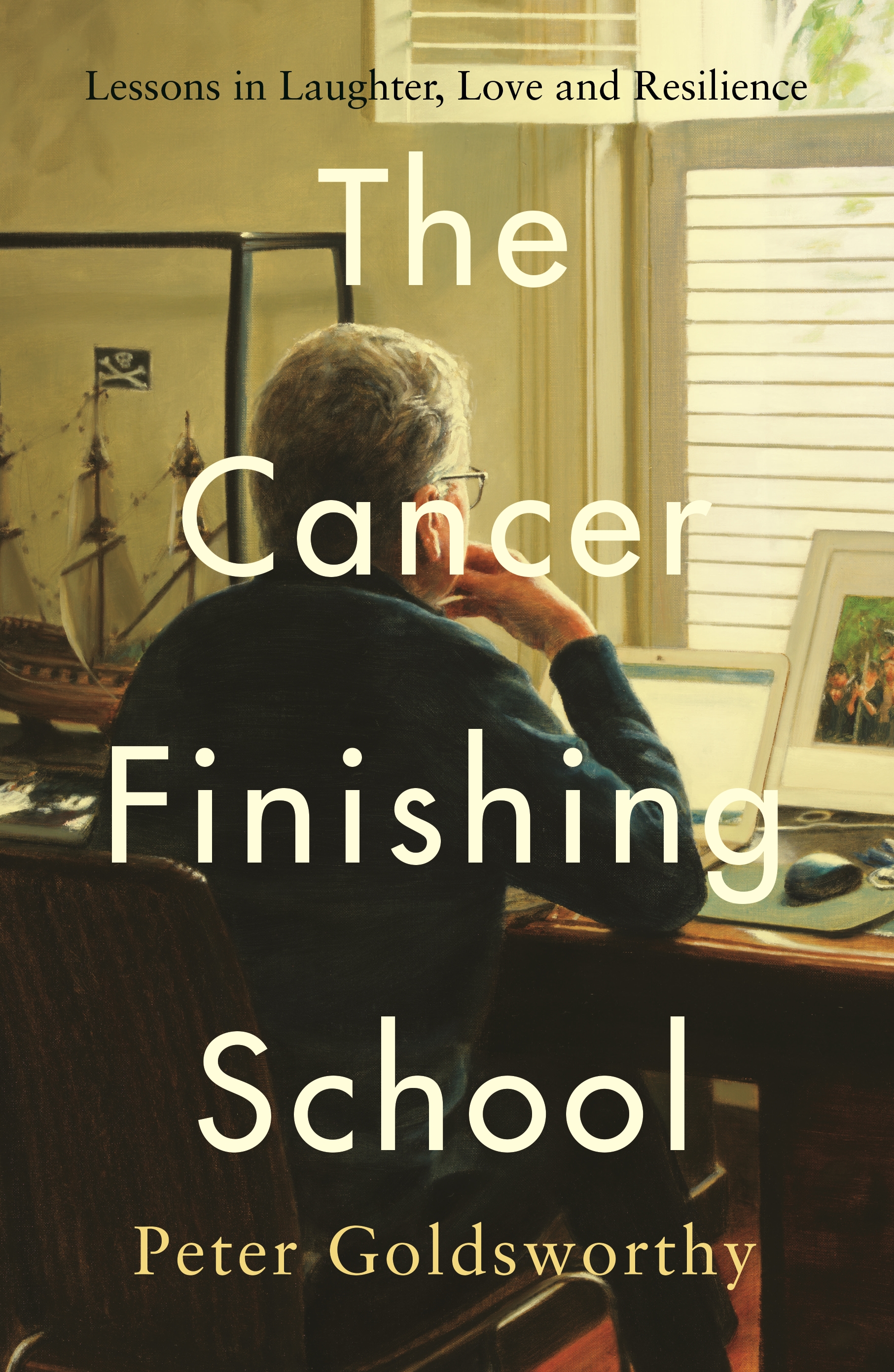

Antoine Reinartz in BPM (Beats per Minute) (Madman Entertainment)

Antoine Reinartz in BPM (Beats per Minute) (Madman Entertainment)

In France, the cinematic achievement of BPM has been recognised. It won the Grand Prix, the FIPRESCI Prize and the Queer Palm at the 2017 Cannes Film Festival, and in March this year earned six César Awards, including Best Film. But in Australia it has been limited to a release at Cinema Nova in Melbourne and Dendy, Newtown, despite screening to acclaim at both the 2017 Melbourne International Film Festival and, nationally, during the 2018 Alliance Française French Film Festival. This is a disappointment, to say the least. At a time when our so-called leaders grow evermore authoritarian and deterministic, the historical provocation that BPM offers is imperative, and in need of witnesses: the past is not a settled question, and nor is the future.

BPM (Madman Entertainment), 140 minutes, directed by Robin Campillo, written by Robin Campillo and Philippe Mangeot. In cinemas May 17.

ABR Arts is generously supported by The Ian Potter Foundation and the ABR Patrons.