Macbeth (State Theatre Company of South Australia) ★★1/2

Macbeth, directed by Geordie Brookman, artistic director of the State Theatre Company of South Australia, is the second production to showcase the STCSA’s new acting ensemble. The first, A Doll’s House, with an updated text by Elena Carapetis and also directed by Brookman, was underwhelming – a limp, misjudged effort whose contemporisation struck a false note and, in giving the final word to Torvald rather than Nora, all but erased the memory of Ibsen’s radical female emancipist approach. In desperate need of a shorter script, the production’s slow-moving revolve became an unfortunate analogy of its laboriousness.

The world of Brookman’s Macbeth – claustrophobic, interiorised – is an oneiric one, taking as its cue Jan Kott’s idea that history in the play is shown ‘as a nightmare’ rather than the ‘Grand Mechanism’ of Shakespeare’s histories. Victoria Lamb’s set is vertiginous, shallow, and brutalist; something like an old Eastern Bloc holding cell with its broken windows, filthy tiling and exposed fittings. When required, a long, slab-like table rises from a floor that, from the play’s opening scene – a wordless prologue in which we see Lady Macbeth (Anna Steen) gorily miscarry, the foundational trauma – thickens with blood (as Kott wrote: ‘A production of Macbeth not evoking a picture of the world flooded with blood would inevitably be false’).

There is a sense, reinforced by an ever-growing chorus of the dead that replaces the play’s usual assortment of attendants, soldiers and messengers, that Brookman’s Macbeth is not so much taking place in a nightmarish world as its world is in itself a nightmare, its dream-logic insisting that the only way Macbeth (Nathan O’Keefe) can break the cycle of killing is to kill again.

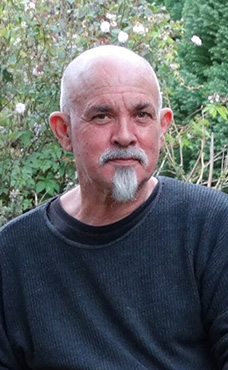

Anna Steen and Nathan O'Keefe in State Theatre Company of South Australia's Macbeth (photograph by Chris Herzfeld, Camlight Productions)

Anna Steen and Nathan O'Keefe in State Theatre Company of South Australia's Macbeth (photograph by Chris Herzfeld, Camlight Productions)

As such, the play’s supernatural elements – Banquo’s ghost, the ‘weyard sisters’, here composited into a single, ghoulish figure (Rachel Burke) who never leaves the stage and discharges blood from her mouth onto Macbeth’s victims – feel more like psychological emanations than evidence of a ‘real’ world that is out of joint; ‘the earth hath bubbles, as the water has’, as Banquo (Dale March) says, while we hear of horses and birds acting strangely, and of the Macbeths’ inability to easily differentiate between day and night. Geoff Cobham’s use of hard, white LED lighting – whether streaming, dappled, through the broken windows, or unforgivingly picking out the Macbeths during their soliloquies – evokes moonlight, a sort of endless, airless pre-dawn, rather than daytime.

But it is difficult to see how Lamb’s realistic set serves Brookman’s oneiric world. Moreover, it is an idea that flattens out the play’s effects to the point of one-dimensionality. Begun as nightmare, and framed by domestic tragedy, the production has nowhere to go, and the audience little feeling for what is at stake. As a result, the concomitant hardening of Macbeth’s resolve and the psychic deterioration of Lady Macbeth – one of Shakespeare’s sharpest structural conceits – is blunted. There is no sense of mounting threat from the army raised by Malcolm and Macduff against Macbeth. Sure enough, the play’s climax is a damp squib, a rushed fistfight that, while perhaps intended to underscore the play’s lack of catharsis, registers simply as indifferent.

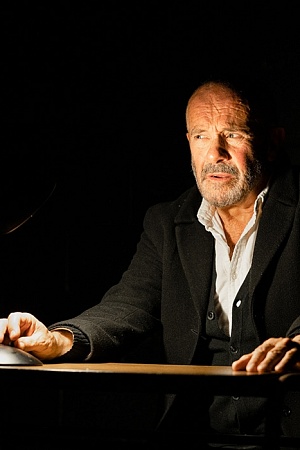

Combined with some inelegant doubling up – Peter Carroll’s barely signalled transition from the murdered Duncan to the jarringly gregarious Porter, and Burke’s turns, while still dressed in the witch’s scabrous garbs, as the children Fleance and MacDuff Jr are particularly egregious – all of this gives the cast much to overcome. To their credit, they acquit themselves well enough. Lean and shaven-headed, O’Keefe is a fine Macbeth, displaying the soldier’s dutifulness rather than the psychotic’s relish in the execution of successive murders. It is a measured performance, free from melodrama, and underpinned by a sound handling of Shakespeare’s verse. If Steen’s Lady Macbeth, driven by personal trauma rather than political ambition, feels more efficient than anything else, then I think it is as a result of the play’s direction. March’s Banquo, Christopher Pitman’s MacDuff, and Rashidi Edward’s Malcolm are solid, if occasionally unintelligible. The ever-present Burke, heavily made-up and moving in almost Noh-like sweeps, works impressively hard to convince us of Brookman’s conception of the witch as a sort of master of puppets, not only prophesying the play’s events but also, seemingly by her incorporeal presence alone, ensuring their coming to pass.

The cast of State Theatre Company of South Australia's Macbeth

The cast of State Theatre Company of South Australia's Macbeth

(photograph by Chris Herzfeld, Camlight Productions)

But it is not enough. As with Brookman’s A Doll’s House, there is a lack of vitality in this production, the sense of a concept too little thought through and too far strained in the quest to reaffirm the significance of these canonical plays. The ensemble, while a laudable initiative, has yet to fully cohere, and can only partially compensate for these shortcomings. If it is to endure – and, holding much promise, I hope it does – its beginnings have been inauspicious ones.

Macbeth (State Theatre Company of South Australia) continues at the Dunstan Playhouse, Adelaide, until 16 September 2017. Performance attended: 29 August.

ABR Arts is generously supported by The Ian Potter Foundation.