Shrine (Kin Collective and fortyfivedownstairs) ★★★

It is a truism that great novelists rarely make great playwrights; Henry James tried to conquer the boards to disastrous effect with Guy Domville (1895), and writers from Virginia Woolf to James Joyce have failed to translate their genius for interiority to the stage. Charles Dickens, whose mastery of scene and dialogue would seem to make him a natural fit for the theatre, never made a good fist of a proper play. Even when adapting their own novels, writers tend to fall apart: Anthony Burgess’s stage adaptation of A Clockwork Orange (1987) is a mess, and a recently rediscovered theatrical version of Lewis Sinclair’s It Can’t Happen Here (1926) is reportedly terrible. Closer to home, we have one shining – if problematic – example of a great novelist who could also write very good plays, and it isn’t Tim Winton. It’s Patrick White, whose stage work is still very much performed and cherished, even if it can be fiendishly difficult to nail. (Andrew Fuhrmann of course devoted his 2013 ABR Fellowship to White’s plays)

Winton has had a rougher foray into the theatre. His first play, Rising Water (2011), was savaged when it played in Perth and later toured, and his most recent play, Shrine (2013), contains serious difficulties of its own. On one hand, Winton has come a long way from that first effort: he seems to have more fully embraced his own cadences, and there is a singularity of purpose that pays off emotionally. On the other hand, with his tenuous grip on structure and pace, he has a way to go.

The shrine of the title refers to those makeshift memorials on the side of roads, amateur rememberances to those lost in motor accidents. This one is to Jack Mansfield (Christian Taylor), who was killed while driving his friends Will (Nick Clark) and Ben (Keith Brockett) home after a night of booze and pot. Jack’s autopsy showed he had no alcohol in his system, but his mates are strangely reticent to offer any explanations for the crash. Jack’s parents, Adam (Chris Bunworth) and Mary (Alexandra Fowler), are understandably adrift. Cut off from each other as much as to the outside world, they poison themselves with grief and resentment. Into this world comes June (Tenielle Thompson), who was with Jack on the last night of his life and who believes she can offer some kind of context to, if not an explanation for, his death.

Nick Clark as Will in Shrine (Kin Collective and fortyfivedownstairs)

Nick Clark as Will in Shrine (Kin Collective and fortyfivedownstairs)

In his recent collection of essays, The Boy Behind the Curtain (2016), reviewed by Peter Craven in ABR's December 2016 issue, Winton relays a seminal episode in his life: his father, who was a motorcycle cop, sustained horrific injuries in a crash and remained an invalid for many years, forever altering the family dynamic. This fact does more than inform the play; it drives it. Adam is the grieving father but he is also the victim, stuck in an existential limbo that may as well be physical. June offers him no catharsis, only a possible way to live on. It is a fraught relationship, and the actors bring it rather touchingly to life. Bunworth, in particular, is superb, roiling and volcanic underneath a weary exterior. He manages to suggest the breezy confidence of the man who was, without cancelling out the image of the man who might grow from these ashes.

The rest of the cast prove as effective as the roles that are written for them. Fowler is given little to work with as the grieving mother, but still manages to find some emotional heft in key scenes. Taylor is simply beautiful as the vibrant and kindly victim, and Thompson is indispensable as the forthright, forgiving young woman who forms a late attachment to him. It is such a pity that Winton decides to depict Jack’s friends as boorish, ultra-privileged psychopaths. Director Marcel Dorney encourages both actors to indulge Winton’s clichés in this area, and the result borders on the cartoonish – a ghoulish depiction of the middle class that is nakedly ideological. These reductive stereotypes cut against the grain of compassion in the play and, more disastrously, threaten its credibility.

In most other ways, Dorney’s direction is robust and sensitive. Winton adopts a register that aims for the incantatory but often comes across as scrappy and schematic, and yet Dorney manages to work the material into sequences of some power. He is less successful with the pace; longueurs are frequent and eventually wearing. Structurally, the play has problems too; it relies so heavily on narration – on isolated characters recalling past events – that it rarely settles into proper scenes; the dramatic potential is undermined. Technically, the production is excellent. Leon Salom’s uncompromising set calls to mind a brutalist fortress as much as a great fissure in a sea wall. Kris Chainey’s lighting design is brilliant, giving everything a grainy texture, as if we are seeing the characters through the mists thrown up by the crashing nearby surf.

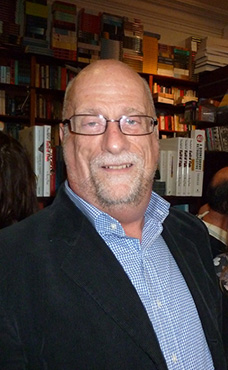

Tim Winton (photograph by Denise Winton)

Tim Winton (photograph by Denise Winton)

There is no denying the poignancy of a play that aims to tackle the senseless horror and abiding loss of road trauma, and Winton doesn’t shy from its incomprehensible ugliness. At one point Mary says, ‘When they’re gone, they leave behind a hole bigger than the space they took up. How is that possible?’ If his grasp of stagecraft – his ability to wrangle the maximum drama and meaning from the language of the theatre – is still lacking, at least his emotional honesty is intact.

Shrine (Kin Collective and fortyfivedownstairs) is written by Tim Winton and directed by Marcel Dorney. The production continues at fortyfivedownstairs until 18 June 2017. Performance attended: 26 May.

ABR Arts is generously supported by The Ian Potter Foundation.