Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra and Jaap van Zweden ★★★1/2

After the recent appearance of Joshua Bell and the Academy of St Martin in the Fields in Sydney, the next visitors to the Sydney Opera House in the World Orchestras Program were the Hong Kong Philharmonic under conductor Jaap van Zweden, with violinist Ning Feng. Although the Concert Hall was again pretty nearly full for their single night in Sydney, there was an absence of the palpable sense of excitement which Bell’s appearance had engendered.

Still, with van Zweden (Music Director of the HKP) at the helm, it was a chance to experience a conductor on the verge of breaking into the very front rank, with the Dutch maestro scheduled to become Music Director of the New York Philharmonic in the 2018–19 season. The announcement of his appointment early in 2016 prompted a typical denunciatory salvo from Norman Lebrecht, which provided much fodder for the online chatterati. As Oscar Wilde sagely noted, however, the only thing worse than being talked about is not being talked about, and the maelstrom of criticism and defence surrounding his name certainly heightened curiosity ahead of van Zweden’s appearance.

Given Hong Kong’s historical significance as a frontier between east and west, the orchestra’s membership was appropriately diverse, although expatriate Western musicians seemed to be much more heavily represented in the wind sections than among the strings. The obligatory contemporary work which opened the concert was by Fung Lam, a Hong-Kong born composer much of whose training had been undertaken in Britain. His program note for Quintessence put forward the idea of an element ‘latent in all living beings’, and hinted at a common core of musical elements unifying the ten-minute composition.

Experientially, however, the first-time listener would have been struck by the work’s diversity rather than by any underlying unity. For the first few minutes, it felt like it was catering to the short-attention spans of modern audiences, with textures changing radically every few seconds. These ranged from extreme violence and activity in the strings à la George Crumb to gentle clusters, from bell chimes to bird-like noises. Many of these were sonically interesting, such as the way a flighted figure was passed from one player to the next down through the first violin section while the double basses took the melodic lead. But it was hard to get any purchase on the whole. Gradually, some of these sections became a little longer and more stable, such as the mellifluous high solo strings supported by woodwind near the end. More than once, Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring seemed to have been a source of inspiration, and the work finished with a similar final outburst.

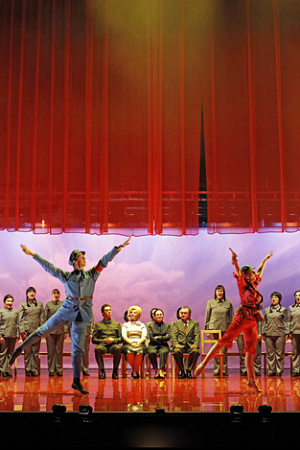

Jaap van Zweden conducts the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra

Jaap van Zweden conducts the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra

(photograph courtesy of the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra)

Ning Feng may lack Bell’s star power, but his performance of Mozart’s Fourth Concerto for Violin was still delectable, if rather old-school. Given how effectively the HIP movement (historically informed performance) has colonised repertoire up to, and in some cases beyond, 1800, this was something of a throwback to an older mainstream performance style, involving a large body of orchestral musicians, lots of vibrato, and a general air of well-mannered predictability. The only obvious trace of HIP practice was when Ning joined in with the body of the orchestra for the opening and closing ritornello sections. His first solo passage was eloquent, and he exhibited a nice variety of tonal shadings throughout. Van Zweden kept the orchestra under wraps, allowing the soloist to be easily heard. The second movement had an idyllic, sunset feel to it, very smooth and lyrical, with fluent double-third decorations in the solo cadenza near the end. The finale illustrates how Mozart plays with genre expectations: the main theme starts out as if it were a gentle clockwork, before suddenly transforming into a faster, more rollicking comic-opera theme. In this performance, the central gavotte and musette were a pleasing contrast to the main material.

Ning Feng on violin (photograph courtesy of the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra)

Ning Feng on violin (photograph courtesy of the Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra)

Given van Zweden’s next major posting, it was good to have heard him conduct Mahler, as the Austrian composer’s symphonies have been central to the repertoire of the New York Philharmonic since Bernstein’s legendary Mahler recordings in the 1960s. On the evidence of Friday night’s First Symphony, van Zweden is thoroughly at home in this music: he negotiated the umpteen tempo changes well, and was able to capture the vast emotional range Mahler spans, from the sunniness of the main theme of the first movement to the angsty despair of the finale. Insofar as this can ever really be said of this repertoire, this was not a self-indulgent performance: van Zweden ensured that the music had clear sense of flow (save the moments of deliberate stasis in the first movement), and gave each movement a narrative arc of its own.

This was made easier by the extreme heterogeneity of the four movements. The first movement involves an act of self-creation: from the extreme stillness of the glassy sustained opening chords, the main material is gradually born (for my money, the primal descending fourths at the beginning might have been more ethereal on Friday night). The main material is based on one of Mahler’s sunnier early songs ‘Ging heut morgen über’s Feld’, and van Zweden phrased it elegantly. The central development which followed felt wonderfully desolate after this, before the explosion back into life towards the end of the movement.

The second movement was played in a dogged fashion here, perhaps excessively so, given that the music has the character of a Ländler. The pay-off came in the trio, which was conceived as a significant contrast with some some welcome Viennese lilt. The third movement is stylistically heterogeneous fantasy that starts out with a minor-mode version of the ‘Frère Jacques’ nursery rhyme on a solo double bass. The quirkiness here was increased by the exaggerated delivery of a subsidiary motif first on the oboes, then the cellos. Later on, the entry of the swaggering Klezmer-like contrasting idea was particularly fine.

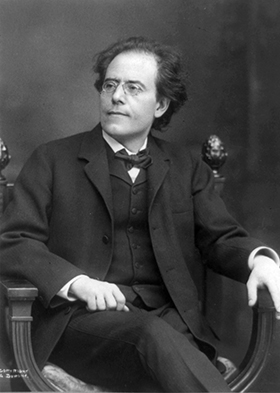

Gustav Mahler, 1909 (A. Dupont, New York, via Wikimedia Commons)Van Zweden hadn’t allowed much slackening of the narrative pace between movements up until this point, but there was no break whatsoever before the finale entered with its visceral dissonance. Everything here was pleasingly tight in the driven main theme, with the swoony Tchaikovskian second theme a luscious contrast. The moment of ‘breakthrough’, a famously deliberate bump where Mahler in effect resets the music a whole step higher than was expected, was dramatic, and the post-breakthrough celebrations saw the brass players stand as they intoned their falling fourths theme, increasing the resemblance the passage has to the theme of ‘And he shall reign for ever and ever’ from Handel’s Hallelujah chorus.

Gustav Mahler, 1909 (A. Dupont, New York, via Wikimedia Commons)Van Zweden hadn’t allowed much slackening of the narrative pace between movements up until this point, but there was no break whatsoever before the finale entered with its visceral dissonance. Everything here was pleasingly tight in the driven main theme, with the swoony Tchaikovskian second theme a luscious contrast. The moment of ‘breakthrough’, a famously deliberate bump where Mahler in effect resets the music a whole step higher than was expected, was dramatic, and the post-breakthrough celebrations saw the brass players stand as they intoned their falling fourths theme, increasing the resemblance the passage has to the theme of ‘And he shall reign for ever and ever’ from Handel’s Hallelujah chorus.

Did one need the Ride of the Valkyries as encore after the existential journey of the Symphony? Perhaps not, and Wagner’s orchestral showpiece inevitably came over as rather crude after the nuance of the preceding work. Still, it confirmed impressions of the Hong Kong Philharmonic as a highly professional, technically proficient group. It might not yet be sonically up there with the major European orchestras, but a thoroughly satisfying account of Mahler’s First is a testimony to them and to van Zweden’s direction.

Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra and Jaap van Zweden performed at the Arts Centre Melbourne on Thursday 4 May, and at the Sydney Opera House on Friday 5 May. Performance attended: 5 May 2017.

ABR Arts is generously supported by The Ian Potter Foundation