Endgame (MTC)

Endgame. The title evokes that moment in chess when few pieces are left on the board, when the end is nigh but neither player can be confident of victory; the sense of an ending looms, but any hope of catharsis or resolution feels indulgent and premature – futile even. When the first words spoken are ‘Finished, it’s finished, nearly finished, it must be nearly finished’, we know we are in a truly liminal space, one that may never be resolved.

Endgame (Fin de partie, 1957)was written, like Samuel Beckett’s other acknowledged masterpiece Waiting for Godot (1953) in French: in order to strip the native Irishman’s work of subconscious affectation, to force him to think and write more fundamentally, he once told the New York Times. Of course, it is no accident that existentialism itself was communicated in this language. Camus and Artaud are often cited as influences on Beckett, even if this was as much a consequence of proximity as ideology. Ionesco and Genet were certainly prosecuting similar concerns, albeit from different vantage points. The result in Beckett was a sparseness that bordered on religiosity – or, in this case, atheistic monasticism.

‘The result in Beckett was a sparseness that bordered on religiosity’

The plot is non-existent: a blind man who can’t stand up berates and cajoles a crippled servant who can’t sit. Their relationship – founded on horror and mistrust – deepens only in its horror and mistrust. Hamm (Colin Friels) and Clov (Luke Mullins) are one of theatre’s great codependent couples, suggestive of Prospero and Caliban as much as of Lear and the Fool, but far more noxious and embittered. The world they inhabit is ruined, blasted, ashen; the sense is less of a cataclysm than of a gradual fade to black. The neighbour Mother Pegg dies ‘of darkness’, and Clov himself says, ‘the earth is extinguished, though I never saw it lit’.

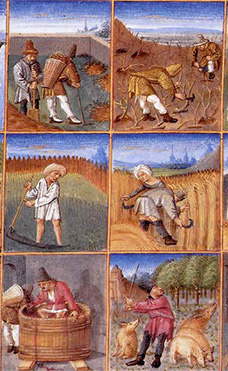

Julie Forsyth as Nell and Rhys McConnochie as Nagg in Endgame

Julie Forsyth as Nell and Rhys McConnochie as Nagg in Endgame

(photograph by Jeff Busby)

Hamm’s parents Nell (Julie Forsyth) and Nagg (Rhys McConnochie) do remember the world as it was, and they indulge their nostalgia in a reminiscence of paddling on Lake Como that startles precisely because it is so specific. The fact that they are confined to rubbish bins only sharpens the elegiac nature of the memory. Forsyth and McConnochie are superb, regressed cherubs pulling on the harp strings of the past but also capable of sudden bursts of defiance and pluck. Their survival is a position, until it becomes unsustainable. As Clov says in the end, ‘If I don’t kill that rat, he’ll die.’

‘The world they inhabit is ruined, blasted, ashen’

Beckett always frustrated critical interpretation of his plays, while furiously protecting what he perceived as their integrity in performance. The result may be a belligerent, not to mention litigious, attitude to productions of his work, but he did have a point. The image of Nagg and Nell popping out of their bins is such an indelible one, so pulsed with meaning and yet so resistant to academic analysis, that it functions on the level of iconography. Hamm and Clov’s labyrinthine banter is similarly ineffaceable, as perfect and despairing as Abbott and Costello’s Who’s on First? routine. There is a hilarious exchange in the play that deals directly with meaning and its futility. Hamm is suddenly struck with a horrifying thought: ‘We’re not beginning … to mean something?’ Clov’s dismissal is devastating, but also slyly disingenuous of the playwright. ‘Mean something! You and I, mean something! (Brief laugh) Ah that’s a good one!’

As the central couple, Friels and Mullins are less than perfect, though considerable amounts of meaning still manage to seep through. The last significant pairing of these roles in Melbourne was of Peter Houghton and David Tredinnick, in an unforgettable production by The Eleventh Hour in 2006), and the comparison isn’t kind. Friels seems simply miscast, although he does grow into the role somewhat. He is a very good at seething egoism, and his casual cruelty lands every time, something to be expected from a classic bully. What is missing is the sense of desperate longing, the cloying heart underneath the gruffness, the frankly poetic and romantic nature of Hamm. Very little elevates the character, and he comes across as pure misanthrope.

Colin Friels as Hamm and Luke Mullins as Clov in Endgame

Colin Friels as Hamm and Luke Mullins as Clov in Endgame

(photograph by Jeff Busby)

Mullins fares better as Clov, yet he too fails to play some key notes. Physically and vocally he is terrific, exacting, and abject. But he overplays the contempt from the beginning, which renders some of the character’s attitudes inexplicable. There is no levity in his performance, and again none of the wistfulness that links him to a grander suffering. The result is that much of the humour and poignancy is lost.

‘The production is funny, but the play is funnier’

Director Sam Strong must take some of the blame for this, although he also deserves credit for its successes. The production is funny, but the play is funnier. Beckett’s rhythms are snappy, and sometimes the gags fall flat due to simple errors of timing. What is undeniable is the production’s attention to detail. The idea of pairing artist Callum Morton with Samuel Beckett was sheer genius. Morton’s set design, a concrete tomb of grey despair, is faultless. The stunning lighting (Paul Jackson) functions as another character, inexorable and frightening. The costumes (Eugyeene Teh) are witty and suggestive.

For all its faults, this production of Endgame proves a point: this is an enduring modernist masterpiece, devastating and endless. It is a play that seems incapable of irrelevance, destined to go on. Of the rat that got away, Hamm says he can’t go far. Clov always has a response, but it’s rarely an answer. ‘He doesn’t need to go far.’

Endgame by Samuel Beckett, directed by Sam Strong for the Melbourne Theatre Company, and performed at Southbank Theatre, The Sumner until 25 April. Performance attended 26 March.