Falstaff (Opera Australia)

With the third of its spring offerings, Opera Australia again demonstrated the overall strength of the ensemble and the consistently fine playing of which Orchestra Victoria is capable.

This Falstaff is a revival of Simon Phillips’s production, first performed in 1995 (Adelaide) and starrily led by Bryn Terfel in 1999 (Sydney), his first Falstaff. Hugh Halliday is the ‘revival director’. The production needs little resuscitation. Everything about it – from Iain Aitken’s entertaining sets to Tracy Grant Lord’s costumes – is absorbing and harmonious, and it looks good on the wide Melbourne stage. At times there were dozens of people – romping or mocking or scheming – but this effusive clutter always worked to comic effect, especially during the hilarious scene in Act II when those merry wives of Windsor bundle the duplicitous knight into an appropriately large washing basket and have him dumped in the Thames.

The genesis of Giuseppe Verdi’s final opera is one of the glories of Italian music. By the 1890s the composer of Rigoletto and La Traviata had little more to prove. Wagner having died a decade earlier, he was incontestably the world’s greatest living opera composer. At one stage newspapers published a rumour that Verdi (already a senator) was about to be ennobled (a prospect that appalled Verdi, who disliked celebrity). The Italian king was amused. ‘The man who is the King of Art in the world today cannot become the marquis of Busseto in Italy,’ Verdi was reassured.

‘The genesis of Giuseppe Verdi’s final opera is one of the glories of Italian music’

Furthermore, Verdi was immensely wealthy in his own right. A major landowner, serious farmer, and brilliant businessman, he had accumulated a fortune that would be valued at six million lire on his death. Mary Jane Phillips-Matz, in her exhaustive and illuminating biography (1993), valued this estate at £14 million in 1990 terms. Andrew Porter has spoken of Verdi’s ‘Shylock-strict exaction of any monies due to him’.

Verdi had entertained the world with operas since Oberto in 1839, the age of Bellini and Donizetti. His operatic career almost ended in 1871, with Aida. A long gap followed until the miraculous Otello in 1887, when he was seventy-three. Verdi encouraged the belief that this was his swansong. But Verdi had always been drawn to Shakespeare. He loved Sir John Falstaff, or ‘Big Belly, as he called him. Gradually, he and Arrigo Boito (composer of Mefistofele and librettist of Otello and Franco Faccio’s Amleto) began to work on a new Shakespeare opera.

Jonathan Abernethy as Fenton and Taryn Fiebig as Nanetta (photograph by Jeff Busby)

Jonathan Abernethy as Fenton and Taryn Fiebig as Nanetta (photograph by Jeff Busby)

Boito’s version of The Merry Wives of Windsor (usually placed in 1597) is a miracle of concision and sympathetic excision. He simplifies the cumbersome and somewhat anomalous drama, of which Tony Tanner remarked: ‘It is a play which unarguably shows signs of hurried composition.’ Boito telescopes four characters into Dr Caius, turns Anne Page into Nanetta Ford and robs her of one suitor, and spares Falstaff one of the three humiliations visited on him by Shakespeare (Mother Prat). He also borrows from the Henry IV plays, principally the lines that form the great Honour monologue in Act I. The spirit of the play is there, of course; and the essence is ludic and benign, as when Page says, ‘Come, gentlemen, I hope we shall drink down all unkindness.’

Finally, amid much secrecy, the opera was extensively rehearsed, though Verdi – ever the martinet in the theatre, even in his eightieth year – continued to chivvy La Scala with threats of withdrawal if he was unhappy with any aspect of the production. Colleagues marvelled at his energy; scientists published articles on his physical resilience.

The première in Milan on 9 February 1893 was a legendary success. Victor Maurel, the original Iago, sang the role of Falstaff. The ovation for Verdi and his cast lasted almost an hour. When Verdi retired to his hotel suite, the pandemonium outside went on so long that Verdi and Boito were forced to appear on the balcony. Verdi, as he always did, stayed for the first three performances. Then he quitted opera forever (though he still had one more gem to write, the Quattro Pezzi Sacri of 1898). When he died in January 1901, a few days after Queen Victoria, 300,000 people observed his memorial service.

‘In many ways, Verdi’s final opera is his most buoyant, most charming, most teasing, most ingenious – and most youthful’

In many ways, Verdi’s final opera is his most buoyant, most charming, most teasing, most ingenious – and most youthful. The score is famously zesty. It resists the staples of Italian opera (the staples of Verdi’s operas) – arias and cabalettas, surging choruses and overtures. Verdi almost dares the audience to interrupt the flow of melodies and musical innovations. They do so at their peril. The opening-night applause that followed Ford’s great scene in Act II merely succeeded in drowning a few bars of this ever-spirited score.

Charles Osborne has written: ‘… the most striking aspect of this opera is its melodic prodigality. Verdi scatters tunes about as though he is trying to give them away. It is the very profusion of splendid tunes in Falstaff which has occasionally led the casual hearer to suppose that it contains no tunes at all.’

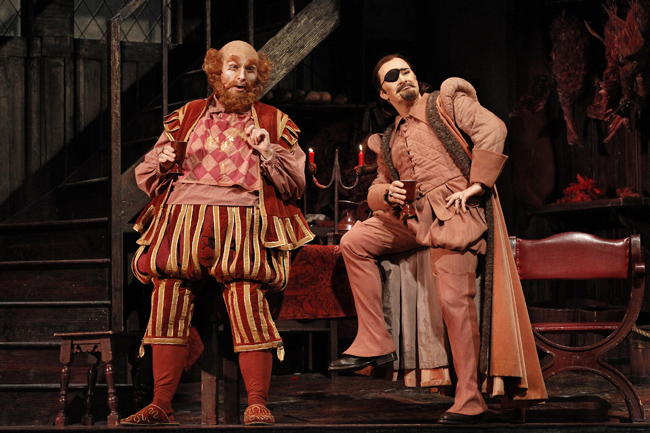

Warwick Fyfe as Falstaff and Michael Honeyman as Ford (photograph by Jeff Busby)

Warwick Fyfe as Falstaff and Michael Honeyman as Ford (photograph by Jeff Busby)

Bernard Shaw chose not to attend the world première. In a long, brilliant paragraph in The World, he advanced his reasons for not travelling to Milan. ‘I am not enough of a first-nighter to face the huge tedium and probable sickness of the journey’ or to ‘[witness] a Grand Old Man demonstration conducted for the most part by people who know about as much of music as the average worshipper of Mr Gladstone does of statesmanship’. Shaw had often railed against the Italian’s treatment of his singers (‘Verdi’s worst sins as a composer have been sins against the human voice’). But he promptly bought the score and devoured it:

Falstaff is lighted and warmed only by the afterglow of the fierce noonday sun of Ernani; but the gain in beauty conceals the loss of heat – if, indeed, it be a loss to replace intensity of passion and spontaneity of song by fullness of insight and perfect mastery of workmanship.

Shaw spoke of ‘the serious part of Falstaff’, wisely adding, ‘there is nothing so serious as great humour’.

Warwick Fyfe – back in form after an uncomfortable season as Rigoletto in April – once again assumed the title role. Among the other fine performances, Michael Honeyman was outstanding as Ford, especially in the big soliloquy that follows his confrontation with his wife’s seducer in Act II; Honeyman generated real indignation. Jonathan Abernethy looked the part as Fenton and was in fine voice for ‘Dal labbro il canto estasiato vola’ in Act III, practically the only conventional aria in the opera. Among the women, Taryn Fiebig was a likeable Nanetta, floating two exquisite high notes during her duet with Fenton; and Jane Ede was exceptional as Alice Ford.

There are so many highlights along the way, fleeting though they are: the simultaneous male quintet and female quartet that end Act I; Mistress Quickly’s (Dominica Matthews) deeply ironic and curtsey-like ‘Reverenza’ when she tricks Falstaff; the comic patter between Falstaff and Ford when they defer to each other at the door; the physical comedy with the washing basket; the brilliant orchestral trill as Falstaff revives himself with a glass of wine; the beautiful writing for the only chorus of the night when Nanetta appears as the Queen of the Fairies; the complex fugue that ends the opera. This home-grown cast, and Orchestra Victoria under Christian Badea, did them all justice.

‘Falstaff has always been one of the most loved characters in literature’

Falstaff has always been one of the most loved characters in literature. Elizabeth I herself, it was suggested in the eighteenth century, requested another play involving Falstaff after the first part of Henry IV. Verdi, the great humanist and scourge of cant, never tired of his finest comic creation. A touching note accompanied the autograph score when Verdi sent it to Casa Ricordi:

It’s all finished. Go on, go on, old John … Go on down your road as far as you can … Entertaining sort of rascal eternally true, beneath different masks, all the time, everywhere!! Go, go on, go on Addio!

Artists of Opera Australia in Opera Australia's Falstaff (photograph by Jeff Busby)

Artists of Opera Australia in Opera Australia's Falstaff (photograph by Jeff Busby)

Four nights later, Arts Update returned for the eighth performance in a long run of Tosca. (We reviewed the first performance here.) The State Theatre was packed to those precipitous top boxes.

Arts Update was there for Jacqueline Mabardi’s first Tosca in the season, following the Austrian Martina Serafin’s departure. Mabardi seemed tentative at first, and her gestures were studied, unconfident. Hers is a light voice for this massive role, and some of Tosca’s outcries and imprecations (‘Assassino’ and ‘Morire’) lost some of their impact. But the top register is very fine and ‘Vissi d’arte’ was well sung. By the end, when she began to forget what she had been told to do with her hands, Mabardi was surer, moving, especially in the duets with Cavaradossi.

Claudio Sgura sang better – more full-throatedly – than he did on opening night, notably during the Te Deum and Scarpia’s Act II politician-like exercise in self-justification before he tries to rape Floria Tosca. But Sgura, a two-dimensional menacer, seems rather young to be playing this psycopath.

Diego Torre as Cavaradossi (Photograph by Jeff Busby)

Diego Torre as Cavaradossi (Photograph by Jeff Busby)

Emphatically, it was Diego Torre’s night. This was magnificent singing from the Bergonzi-like Mexican tenor: ardent, ringing, utterly assured. ‘E lucevan le stelle’ was unforgettable, so good in fact the audience sat there in rightful silence as Puccini brought on Tosca for the tender, plotful duet that follows: another melodious essay in Puccini’s famous hand fetish.

Opera Australia’s final calls, sans curtain, are modishly democratic (if not always well choreographed), but there are times when the company should employ that copious bouquet of a curtain to allow supplementary solo calls. The audience knew it had just been treated to some of the finest tenor singing heard here in years, and Torre deserved a second huge ovation.

Puccinians, and lovers of grand singing, should not miss the last two performances, on the tenth and thirteenth.

Falstaff, directed by Simon Phillips for Opera Australia. Performances continue at the State Theatre, Art Centre Melbourne until 11 December. Performance attended 1 December.

Tosca, directed by John Bell for Opera Australia. Performances continue at the State Theatre, Art Centre Melbourne until 13 December. Performance attended 5 December.